“For all the world I was led like a dancing bear” by NC Wyeth (1911).

This year’s reading began with a desire to explore some of the Robert Louis Stevenson volumes in my collection which I’ve so far neglected. At the moment I’m thinking of maybe reading everything I have by RLS, having begun with a return journey to Treasure Island, a book which seems to improve every time I revisit it. Setting out with Stevenson’s pirate tale was partly a result of having watched all three Pirates of the Caribbean films over Christmas, a series I’m probably in the minority in enjoying wholeheartedly, flaws, preposterousness and all. Much as I’d like to see a fourth film (there’s a hint of a sequel at the end), I’d prefer the makers to leave things be. The three films taken together can be watched as a single nine-hour ramble across the high seas and the tidy conclusion would be better left as it is.

My pocket-sized copy of Treasure Island from the Tusitala edition of Stevenson’s collected works is fine apart from the very small and poorly-printed map, something to which the reader is compelled to refer as we follow Jim Hawkins on his journey around the island. Happily the web provides many examples which can be printed out for viewing while reading. The web is also a resource for some of the numerous illustrated editions of the novel. The version by American illustrator NC Wyeth is one of the more well-known and more successful and his Long John Silver is a suitably powerful figure. Wyeth’s depiction of Billy Bones waiting on the cliff top was featured in a set of US stamps in 2001. The Internet Archive has scans of the Wyeth book (and a version with illustrations by Louis Rhead) although one of these, with better scans of Wyeth’s paintings, has some of the plates missing.

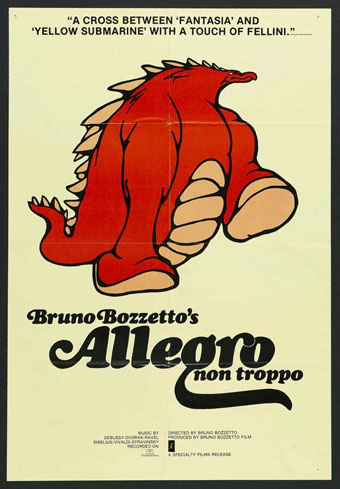

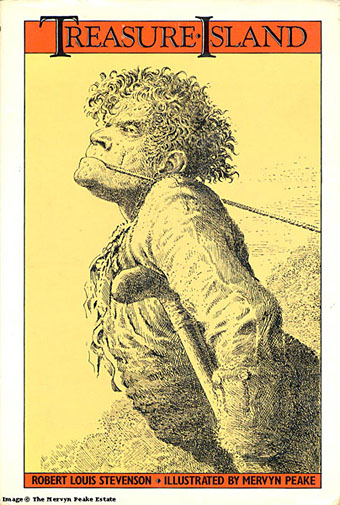

Long John Silver by Mervyn Peake (1949).

Far stranger—weirder, even—is Mervyn Peake’s Long John Silver, seen here on the cover of a more recent edition. Peake’s illustrations are probably my favourites but then I’m biased towards Peake as an author and illustrator so the preference is unavoidable. Even so, his depiction of Israel Hands brings to the fore the malevolent duplicity of that character in a way I’ve not seen any other illustrator attempt. It’s a shame the Peake site doesn’t have another of the artist’s renderings of Silver showing the sea cook posed on his single leg in an attitude more like a ballet dancer than a pirate. That drawing and his ogre-like Blind Pew show how original Peake could be as an illustrator. And lets not forget his own pirate creation, also his first book, Captain Slaughterboard.

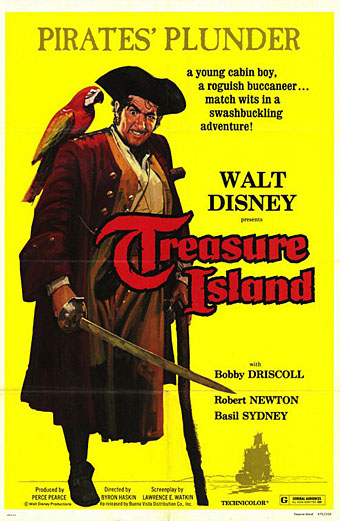

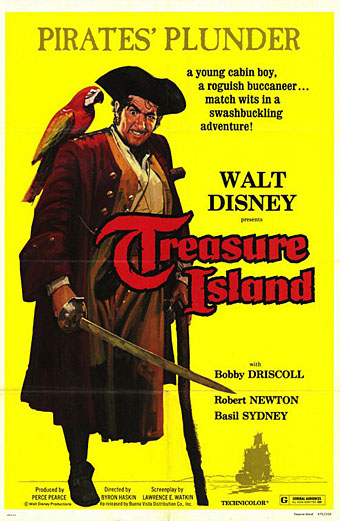

It’s asking too much but it’s a shame that Walt Disney couldn’t have taken a look at Peake’s drawings instead of diluting Stevenson’s cunning buccaneer into the gurning caricature portrayed by Robert Newton in 1950. The less said about Byron Haskin’s film (and its sequels), the better. It has its moments visually but Newton’s portrayal has blighted all those that follow (Geoffrey Rush tips the hat in the Pirates films) and is single-handedly responsible for all subsequent pirate clichés.

Davy Jones from Pirates of the Caribbean, on the other hand, could almost have been designed specifically to please me alone, looking like the offspring of some unwholesome ménage between Long John Silver and the Great God Cthulhu. For the time being Davy Jones is probably my favourite screen villain, his tentacled face—and the fishy caste of his crew—is a wonder to behold. God knows what Stevenson would have made of this transfiguring of his creation but it suits me fine.

More buccaneers tomorrow.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mervyn Peake in Lilliput

• Stevenson and the dynamiters

• Howard Pyle’s pirates

• Druillet meets Hodgson

• Rogue’s Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs, and Chanteys

• Davy Jones