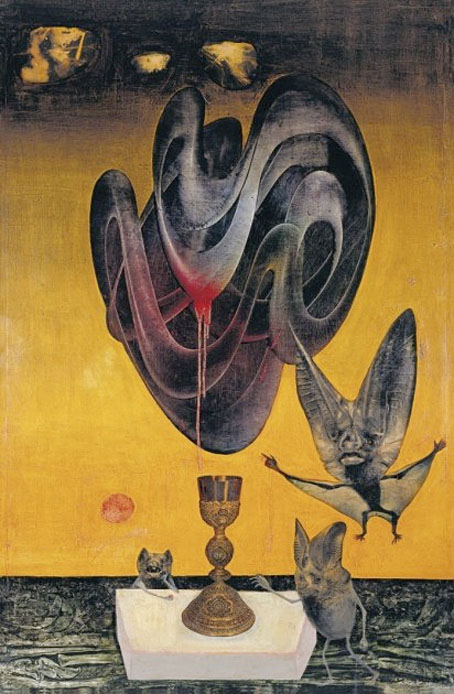

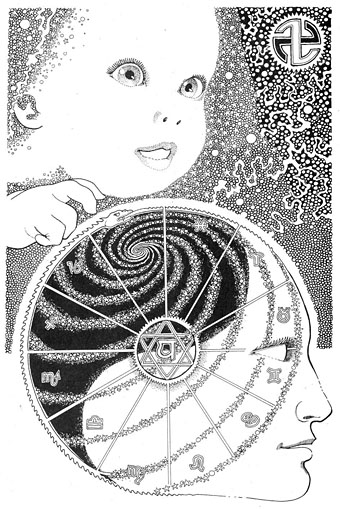

A painting by Stephen Mackey.

• “Creativity is visual, not informed thought. Creativity is not polite. It barges in uninvited, unannounced—confusing, chaotic, demanding, deaf to reason or to common sense—and leaves the intellect to clear up the mess. Above all else, creativity is risk; heedful risk, but risk entire. Without risk we have the ability only to keep things ticking over the way they are.” Revelations from a life of storytelling by Alan Garner. Related: Tygertale on Garner’s Elidor (1965), “the anti-Tolkien”. The BBC’s 1995 adaptation of Elidor remains unavailable on DVD but may be watched on YouTube.

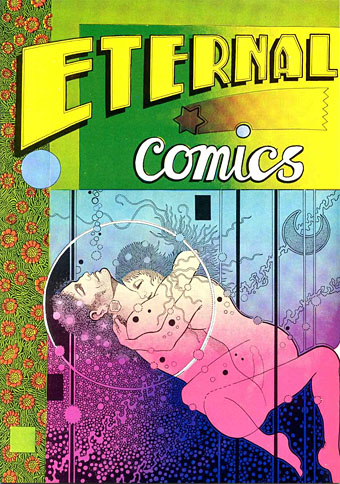

• “One of my revelations was to reverse everything I’d been taught. Making lettering as illegible as possible falls into that way of thinking.” Psychedelic artist and underground cartoonist Victor Moscoso talks to Nicole Rudick about a life in art and design. Related: “I’ve gotten a lot of bad write-ups in newspapers over the years and they like to refer to my stuff as ‘kitsch’…Well, my stuff is way fuckin’ kitsch. It’s kitsch to an abstract level, you understand. It’s fuckin’ meretricious.” I love it when Robert Williams kicks the art world.

• “…a cerebral, challenging, visually stunning piece of 1970s American science fiction that enweirds the human perspective by challenging it with a nonhuman one.” Adam Mills on the inhuman geometries of Saul Bass’s Phase IV.

• “[Delia Derbyshire] taught me everything I knew about electronic music.” David Vorhaus talks to David Stubbs about White Noise and why he prefers the latest technology to old synthesizers.

• Costumes from Alla Nazimova’s film of Salomé (1923) have been discovered in a trunk in Columbus, Georgia.

• Mix of the week: The Ivy-Strangled Path Vol. I, “music for a residual haunting” by David Colohan.

• At Dangerous Minds: Queer, boho or just plain gorgeous: photographs by Poem Baker.

• Grimm City, a speculative architectural project by Flea Folly Architects.

• Mad Max: “Punk’s Sistine Chapel” – A Ballardian Primer.

• In Search of Sleep: photographs by Emma Powell.

• Drains of Manchester

• Road Warrior (1985) by The Dave Howard Singers | Warriors Of The Wasteland (Original 12″ mix, 1986) by Frankie Goes To Hollywood | Drive It Mad Max (Super Flu Remix, 2009) by Marcus Meinhardt