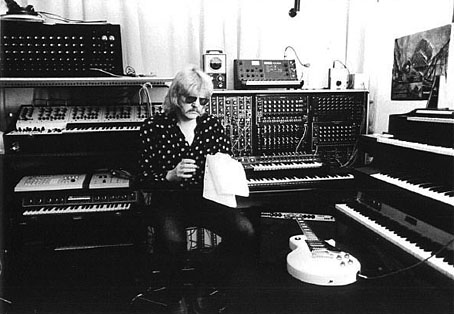

“I was a big fan of Kraftwerk, Cluster and Harmonia, and I thought the first Neu! album, in particular, was just gigantically wonderful,” admits Bowie. “Looking at that against punk, I had absolutely no doubts where the future of music was going, and for me it was coming out of Germany at that time. I also liked some of the later Can things, and there was an album that I loved by Edgar Froese, Epsilon In Malaysian Pale; it’s the most beautiful, enchanting, poignant work, quite lovely. That used to be the background music to my life when I was living in Berlin.”

David Bowie, Mojo magazine, April 1997

Epsilon In Malaysian Pale was Froese’s second solo album released in September 1975. That month David Bowie was in Los Angeles recording his Station To Station album, the opening of which features phased train sounds that are strikingly similar to those that run through the first side of the Froese album. I’ve never seen this similarity mentioned by Bowie scholars but if there was an influence it’s a good example of the degree to which Tangerine Dream infiltrated the wider culture as much as Can and Neu! (Kraftwerk remain in a league of their own.)

All you need is Zeit. Cover painting by Edgar Froese.

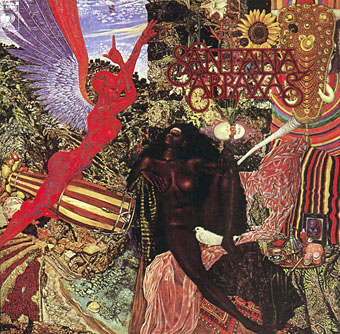

The influence of Tangerine Dream’s albums on the Ohr and Virgin labels is now so widespread that it’s difficult to compile a definitive list of those who’ve either paid homage or copied the group’s trademark style of extended sequencer runs and phased chords. Offhand I could mention the Ricochet-like tracks on Coil’s Musick To Play In The Dark Volumes 1 & 2; the many moments on the early Ghost Box albums, one of which samples from Alpha Centauri; and some of Julian Cope’s more out-there recordings from the late 1990s. There’s also all the releases by a group of loosely affiliated musicians dedicated to maintaining the 70s sound of Mellotrons and bouncing sequencers; many of these I’ve yet to hear but I’ve enjoyed the albums by Node and Redshift.

Tangerine Dream have been a continual fixture in my music listening since I was a teenager; I drew most of The Call of Cthulhu to a soundtrack of Rubycon and Jon Hassell’s Aka/Darbari/Java album. I kept up with them after they departed from Virgin then jumped ship in 1986 after Johannes Schmoelling left the group. The albums continued to proliferate in recent years to an extent that even the Freeman brothers only follow the discography (with some exasperation) up to 1990 in their redoubtable Krautrock tome The Crack in the Cosmic Egg. Navigating a late career is a tricky business for a popular musician so you can’t blame Froese for carrying on the project. Those early recordings are the important ones, and he was a crucial component in their creation.

There’s a lot of Froese and TD on YouTube. If you like the early material these are some of the better moments:

• Bath Tube Session, 1969: TD in psych-freakout mode. Klaus Schulze on drums, and lots of German heads looking bemused/bored.

• Ossiach Lake, 1971: Playing outdoors for the TV cameras.

• Paris, 1973: Footage of the group improvising in the manner of the Atem album.

• Coventry Cathedral, 1975: Tony Palmer’s film of one of the cathedral concerts which caused them to be banned by the Pope from playing in churches. The original sound on this one is lost so the YT version has edits of the Ricochet album as the soundtrack.

• London, 1976: Great film of the Ricochet period. Total synth porn.

• Thief, 1981: The opening scene to Michael Mann’s thriller, and one of their best soundtrack moments. In The Wire this month John Carpenter enthuses about the TD score for Sorcerer but I’ve always felt Mann’s crime drama was a better match for their sound.

• Warsaw, 1983: A Polish TV recording of the concert documented on the Poland (1984) album.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Synthesizing

• Tangerine Dream in Poland

It’s the same every year, the weather gets hot (30C today) and out come the Main CDs, although the march of progress has meant importing them into iTunes this time round. For some reason Main’s Hz collection (6 EPs, later a double-disc set) is especially suited to warm temperatures, partly due to remembrance of them being released one a month during the hot summer of 1995.

It’s the same every year, the weather gets hot (30C today) and out come the Main CDs, although the march of progress has meant importing them into iTunes this time round. For some reason Main’s Hz collection (6 EPs, later a double-disc set) is especially suited to warm temperatures, partly due to remembrance of them being released one a month during the hot summer of 1995.