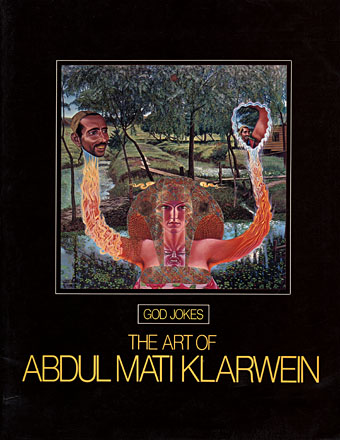

If book collecting is frequently a waiting game, some waiting periods can be longer than others. In the case of Mati Klarwein’s God Jokes, my patience and hope have sustained themselves for 28 years until I finally acquired a copy this Thursday afternoon. God Jokes was the second book of Mati Klarwein’s work, published by Harmony Books, New York, in 1976, a slim catalogue-style collection of his paintings, some of which were featured in the early issues of Omni magazine. In 1979 and 1980 God Jokes turned up in a chain of UK remainder shops and for a while it seemed like everyone I knew owned a copy which possibly explains my unaccountable decision to avoid buying one myself. As the years passed and I became increasingly enamoured with Mati Klarwein’s work I came to regret that decision, not least because the book seemed to disappear completely. Copies have turned up since on Abe.com but at bizarrely inflated prices (£50 for a 56-page art book?!). I paid £4.99; patience sometimes pays off.

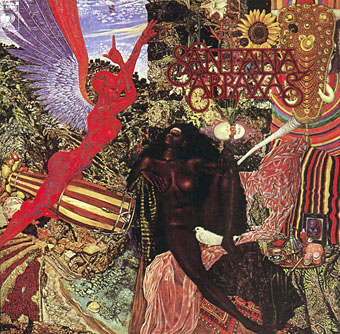

Abraxas by Santana.

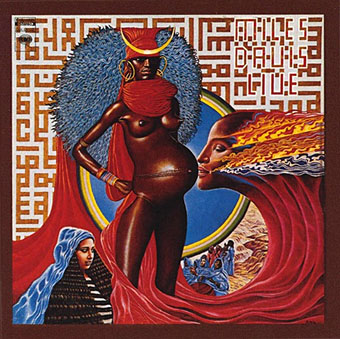

Mati Klarwein’s work has been most visible via the album sleeves of the Sixties and Seventies which borrowed his pictures for their covers. Chief among these is one of the best Santana albums, Abraxas (1970), which used his stunning 1961 painting The Annunciation (and a lettering design by Robert Venosa), and one of all-time favourite albums, the Miles Davis masterpiece Bitches Brew (1970). Miles Davis was a great Klarwein enthusiast for a while and commissioned new work for his Live-Evil album in 1971.

Live-Evil by Miles Davis.

It’s not necessary to go into detail describing Mati Klarwein’s work when you can go to the web gallery maintained by his family and feast your eyes there. Klarwein is one of the few 20th century artists to have taken Salvador Dalí’s photo-realist painting style and make of it something unique to himself; his work is always immediately recognisable. That this work is still known mainly for its illustrative connections tells you more about the iniquities of the art world than it does about the value of the paintings as works of art.

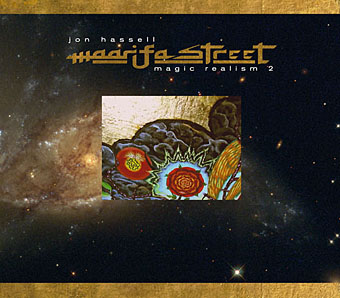

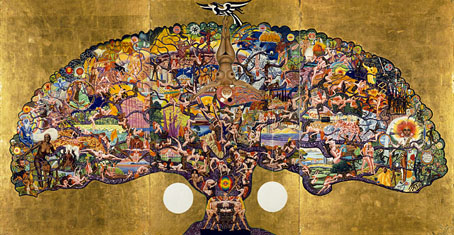

The most curious thing about having to wait so long to find a copy of God Jokes was that I ended up working with a picture of Mati Klarwein’s three years before I found the book; I would have expected to find the book one day but the latter eventuality was far less predictable. In 2005 Jon Hassell asked me to design his new CD, Maarifa Street, and Jon was keen to use a tiny video detail he made of a huge and incredible Klarwein painting, Crucifixion (1963–65). The detail is the rectangle in the centre of the cover, juxtaposed against some Hubble galaxies: the very small against the very large. We used the painting itself and further details inside the digipak. Jon was another of those who used Klarwein’s art for his album sleeves (for Earthquake Island, Dream Theory in Malaya and Aka-Darbari-Java/Magic Realism) and the two men became great friends as a result.

Crucifixion by Mati Klarwein.

Jon Hassell writes about Bitches Brew—and Mati Klarwein’s sleeve art—here. His site also includes a 1998 Mati Klarwein interview from The Wire in which the painter discusses his life and work. If you want a copy of God Jokes for yourself, be prepared to wait…or pay over the odds.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

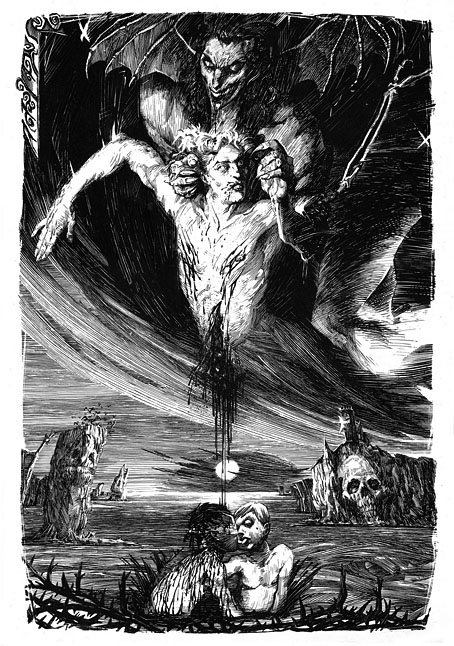

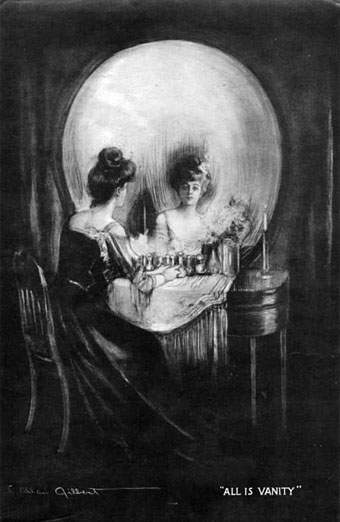

• The fantastic art archive

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ballantine Adult Fantasy covers

• Visions and the art of Nick Hyde

• The poster art of Marian Zazeela

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.