Martyrdom of Saint Denis, Saint Eleutherius and Saint Rusticus by Pierre II Mignard.

Consider this an addendum to an earlier post about decapitations in art history. What I didn’t know then was that decapitated saints have their own “cephalophore” category if they’ve been recorded as going for a post-decapitation stroll; a case of “take up thy head and walk”. Saint Denis of Paris receives more attention than most on account of his being a patron saint of France. This also explains why his martyrdom is depicted in gory detail on the wall of the Pantheon in Paris.

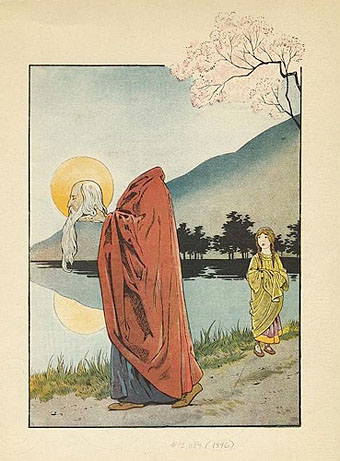

St. Denis bearing his head and halo (1896).

Nine-year-old Saint Justus of Beauvais differs from the strolling cephalophores—who manage to walk some distance before finally expiring—in having picked up his head severed head and carried on speaking. Rubens is one of the few artists to depict this event, although his habitual all-shall-have-muscles technique makes the boy look a lot older. Wikimedia Commons has a few more examples of Saint Denis, with and without head.

The Miracle of Saint Justus (c. 1635) by Peter Paul Rubens.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Decapitations