“Existence has always been precarious. At any stage of its career, humanity might have been exterminated by some slight alteration to its chemical environment, by a more than usually malignant microbe, by a radical change of climate, by the manifold effects of its own folly.”

I loved this, but then it had several points immediately in its favour: a late work by Jóhann Jóhannsson (with a superb score written in collaboration with Yair Elazar Glotman); a study of the concrete memorials from the former Yugoslavia known as spomeniks; narration by Tilda Swinton; and science fiction that isn’t more tiresome Hollywood space opera. Olaf Stapledon’s novel was published in 1930 but it took until 2017 for it to reach a cinema screen when Jóhannsson’s film was premiered at the Manchester International Festival. The film is not only the first adaptation of the novel but also the first film based on any of Stapledon’s novels. Last and First Men and Star Maker (1937) have inspired many notable writers but the philosophical nature of Stapledon’s work combined with the colossal spans of time he deals with make his novels resistant to adaptation by popular narrative forms. Jóhannsson’s film is very small-scale—mostly black-and-white, and shot on grainy 16mm—but it demonstrates how a work that those with greater resources might consider unfilmable can be turned into a substantial drama. The technique of using narration to connect disparate images is a familiar one from documentaries but is less common in fiction cinema despite its flexibility and convenience, especially for low-budget films such as this.

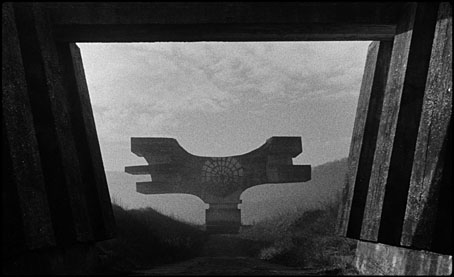

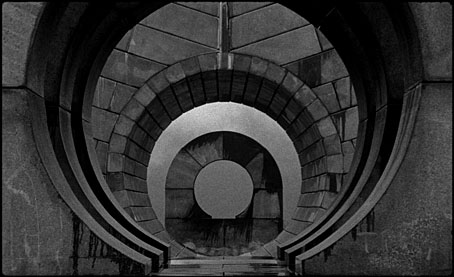

Tilda Swinton’s voice is that of a spokesperson for “the Eighteenth Men”, a terminal evolution of the human species 2,000 million years in the future. The last humans now live on the planet Neptune, a forced relocation after the expansion of the Sun has made the inner planets of the solar system uninhabitable. Swinton’s unidentified messenger is speaking to us, “the First Men”, describing some of the history that awaits while also warning of an impending and inescapable cataclysm. This is the last section of Stapledon’s novel, the previous chapters of which relate the intervening aeons between our time and the distant future. While the voice informs us about humanity’s fate we contemplate the enigmatic spomeniks, filmed in close-up or at a distance, in bright sunlight or shrouded in mist. What connection there is between the narration and the concrete structures is for the viewer to decide, there are few points of direct correspondence. The combination of strange architectural forms with a vast, invented history had me thinking of At the Mountains of Madness by HP Lovecraft, although in Lovecraft’s story the stellar evolution is an alien one which human beings discover. The congruence is reinforced by Lovecraft’s enthusiasm for Stapledon’s novel which he called “a thing of unparalleled power“. It should be noted, however, that Jóhannsson never suggests that the monuments are anything other than what they are.

Roger Luckhurst’s Sight & Sound review of the film included questions about the use of the spomeniks, while elsewhere Owen Hatherley has expressed concern about the fetishising of memorials and structures that mark sites of wartime massacre. Stapledon’s novel explores the continuity of human endeavour in all its best and worst aspects; warfare and strife remain persistent problems, so Jóhannsson’s roaming views may be taken as signposts to the future as much as remembrances of the past. There’s also one significant detail that many critics will be unaware of (and which Luckhurst does acknowledge): the first part of the novel is titled “Balkan Europe”, and the opening chapters describe the wars that ravage the Earth throughout the 21st century, wars which have their root in the very conflicts that the spomeniks record. Stapledon’s future history was an attempt to consider the ways in which humanity might overcome its worst impulses. Beyond this, the concrete structures also stand as simple markers of the passage of time; many of the monuments are now weathered and eroded, blained with lichens and besieged by weeds. Humanity may live long enough to resolve its own internal conflicts but its creations, whatever they represent, face a continual struggle against the universal process of entropy.

Jóhannsson’s film is available in a digipak release from Deutsche Grammophon which packages a blu-ray disc with a CD of the score. This is now a memorial to its creator so the sombre livery seems appropriate: the last major work we’ll have from a remarkable, much-missed artist.

Further reading: The Spomenik Database.