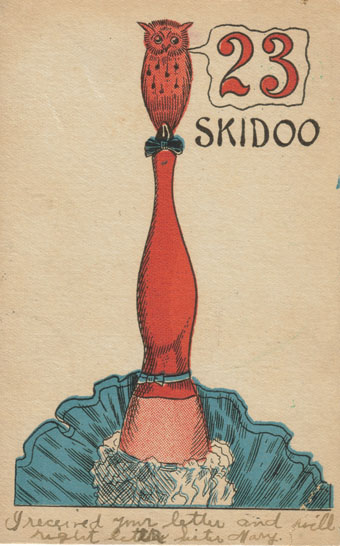

1: A slang phrase

Postcard via.

From the Oxford English Dictionary:

skidoo, v. N. Amer. slang. (ski’du:) Also skiddoo. [Orig. uncertain, perh. f. skedaddle v.]

2. In catch-phrases. a. Used as an exclamation of disrespect (for a person). Esp. in nonsense association with twenty-three. (temporary.)

1906 J. F. Kelly Man with Grip (ed. 2) 99 As for Belmont and Ryan and the rest of that bunch, Skidoo for that crowd when we pass. Ibid. 118 ‘I can see a reason for ‘skidoo’,’ said one, ‘and for ‘23’ also. Skidoo from skids and ‘23’ from 23rd Street that has ferries and depots for 80 per cent. of the railroads leaving New York.’ 1911 Maclean’s Mag. Oct. 348/1 Surrounded by this conglomerate procession as I went on my way, the urchins would yell ‘Skidoo,’ ‘23 for you!’

b. spec. as twenty-three skidoo: formerly, an exclamation of uncertain meaning; later used imp., go away, ‘scram’.

1926 C. T. Ryan in Amer. Speech II. 92/1, I really do not recall which appeared first in my vocabulary, the use of ‘some’ for emphasis or that effective but horrible ‘23-Skiddoo’—perhaps they were simultaneous. 1929 Amer. Speech IV. 430 Among the terms which the daily press credits Mr. Dorgan with inventing are:…twenty-three skiddoo (go away). 1957 W. Faulkner Town iii. 56 Almost any time now Father would walk in rubbing his hands and saying ‘oh you kid’ or ‘twenty-three skidoo’. 1978 D. Bagley Flyaway xi. 80 This elderly, profane woman…used an antique American slang… I expected her to come out with ‘twenty-three, skidoo’.

2: An esoteric poem by Aleister Crowley

[23]

SKIDOO

What man is at ease in his Inn?

Get out.

Wide is the world and cold.

Get out.

Thou hast become an in-itiate.

Get out.

But thou canst not get out by the way thou camest in. The Way out is THE WAY.

Get out.

For OUT is Love and Wisdom and Power.

Get OUT.

If thou hast T already, first get UT.

Then get O.

And so at last get OUT.

From The Book of Lies (1912/13)

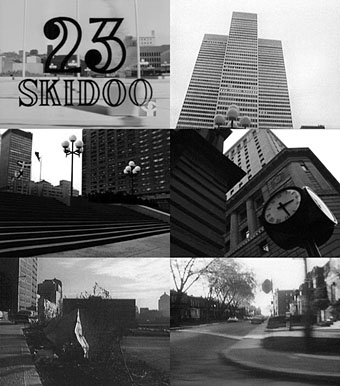

3: A film by Julian Biggs

23 Skidoo (1964).

If you erase the people of downtown America, the effect is bizarre, not to say disturbing. That is what this film does. It shows the familiar urban scene without a soul in sight: streets empty, buildings empty, yet everywhere there is evidence of recent life and activity. At the end of the film we learn what has happened.

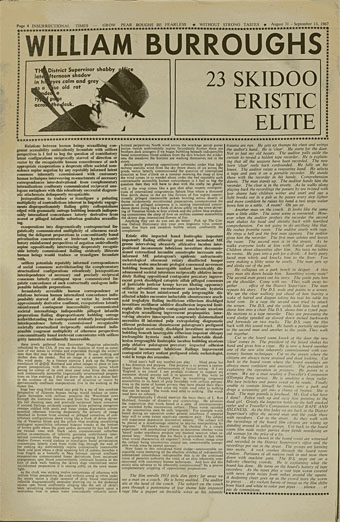

4: 23 Skidoo Eristic Elite by William Burroughs

International Times, issue 18, Aug 31–Sept 13, 1967.

From Burroughs proceed to Illuminatus! (1975) by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, and many subsequent derivations.

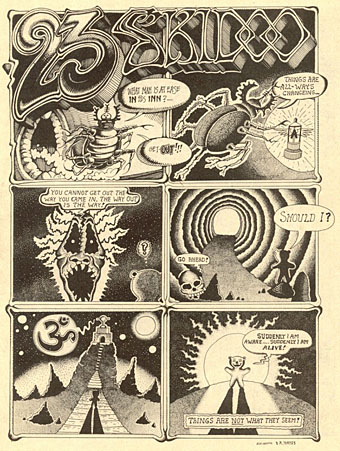

5: A one-off comic strip by Rick Griffin and Rory Hayes

From Bogeyman Comics #2 (1969).

6: A music group

Just Like Everybody (1987). Design by Neville Brody.

7: A poetry collection by Eckhard Gerdes

23 Skidoo! 23 Form-Fitting Poems (2013) by Eckhard Gerdes.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Seven Songs by 23 Skidoo

• 23 Skidoo by Julian Biggs

• Neville Brody and Fetish Records