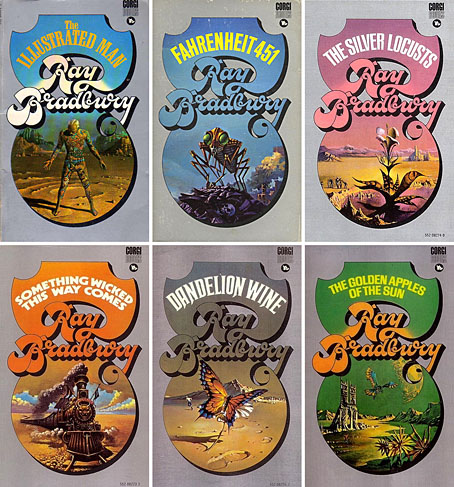

Phase IV (1974).

It’s been a thrill recently poring over the Saul Bass monograph, Saul Bass: A Life in Film & Design by Jennifer Bass & Pat Kirkham, a large volume that weighs a ton and is as revelatory about the career of a great designer (and his wife and frequent collaborator, Elaine Bass) as you’d hope. One pleasure was getting to read about Bass’s film work from his own viewpoint for once. The curious science-fiction film he made in 1974, Phase IV, is well-known enough to have a cult reputation but too often his long involvement with Hollywood is passed over as a footnote to the careers of the directors for whom he worked. In addition to his celebrated title sequences, Bass was also a visual consultant responsible for the planning and filming of what used to be called “special sequences” within films, the most notorious of which is the endlessly argued-over shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). (See this authoritative post by Pat Kirkham on Bass’s special sequences, and the disputed history of those few seconds of black-and-white film.)

Phase IV (1974).

All of which sent me to YouTube looking for some of the shorter films that Bass directed from the mid-60s on. The monograph explores these and Phase IV in some detail, for the latter showing pages of sketches for unfilmed sequences. I’m not sure these would have improved a film which I find flawed and occasionally ludicrous but it’s good to see what the director had in mind. The film on DVD has no extras at all but a trailer can be found on YouTube that shows off some of the startling imagery, and also includes a few shots that were cut by distributors foolishly eager to try and sell it as a horror film. It’s ironic that a man who gained world recognition for his poster designs wasn’t allowed to design the poster for his own film.

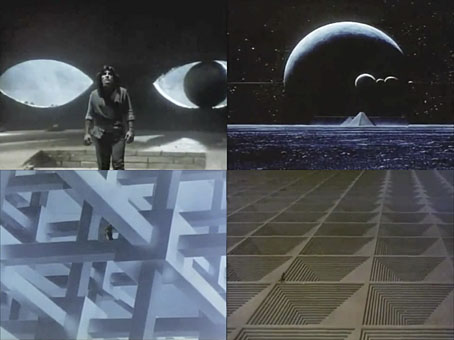

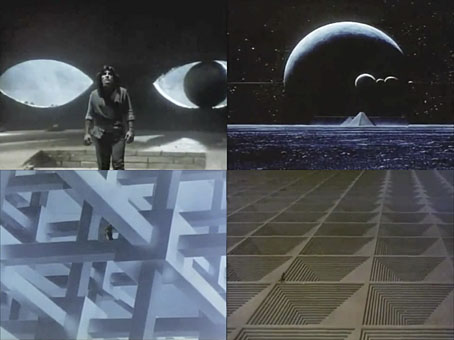

Quest (1984).

Of the short works there’s Why Man Creates (1968) here and here, an examination of the creative impulse that’s been so popular with art teachers over the years that it’s probably been seen by a lot more people than his marauding ants. Both this and The Solar Film (1980), a documentary about solar energy, utilise Bass’s hand-drawn animation. The latter is also of note for its final shot of a baby walking into a sunset, a still of which was turned by Bass into an album cover for Stomu Yamashta in 1984. Also that year, Saul and Elaine produced their strangest work, Quest, a half-hour piece of science fiction based on a Ray Bradbury short story whose quest theme is overly-familiar from a dramatic point-of-view but which typically yields a wealth of memorable visuals. In Phase IV there was a nod to Dalí with the dead man’s hand filled with burrowing ants; in Quest we find imagery borrowed from Magritte (a floating castle-topped mountain) and MC Escher (his Cubic Space Division). The copy on YouTube is rough quality but it’s certainly worth a watch. I’m amused to discover how much Saul & Elaine were prog-rock heads (not that there’s anything wrong with that…): Phase IV has Stomu Yamash’ta and David Vorhaus from White Noise on its soundtrack, The Solar Film features a dubious cover version of Tubular Bells, while the score for Quest is mostly original music (with some borrowings from Holst) that sounds much of the time like Tangerine Dream when they were leaning on their Mellotrons.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Saul Bass album covers

• Pablo Ferro on YouTube