“I know things, and feel things, but the wrong way round. That’s me: all the right answers at none of the right times. I see and can’t understand. I need to adjust my spectrum, pull myself away from the blue end. I could do with a red shift. Galaxies and Rectors have them. Why not me?”

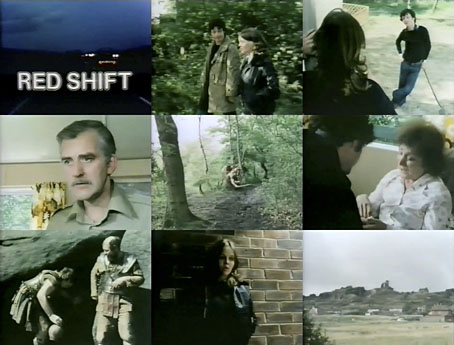

Red Shift by Alan Garner

More fields in England. It’s good to find this TV film on YouTube since I’ve been telling people about it for years. Red Shift (1973) is classed as the last in Alan Garner’s initial run of fantasy novels, although it’s arguable whether it’s a work of fantasy at all. The themes are typical Garner: the Cheshire landscape, and the long hand of the historic past reaching into the present. Instead of a single story there are three interwoven narratives taking place in different eras: Roman Britain, with an invading legion (based on the lost Ninth Legion) being hunted down by the natives; the English Civil War, and the true story of a massacre that took place at a village church; the present (1973) with teenager Tom struggling to maintain a relationship with his girlfriend, Jan, who’s leaving to study as a nurse. Tom’s narrative is the principal one but each thread contains echoes of the others. Connecting them all is a stone axe head buried by one of the Roman soldiers which is found by a villager hundreds of years later then rediscovered in turn by Tom. It’s a fascinating novel which prefigures Alan Moore’s Voice of the Fire (1996) for the way a single location is examined at different periods of history.

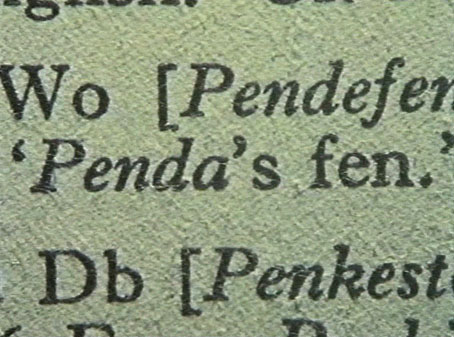

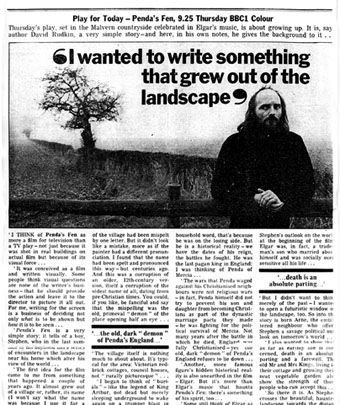

The 75-minute film of Red Shift (1978) was made for the BBC’s Play For Today strand, as was that cult item of mine, Penda’s Fen (1974), and the two have much in common. Writer David Rudkin talked about the “layer upon layer of inheritance” in the Malvern Hills where Penda’s Fen is set, a description that could equally apply to Red Shift. Both plays have intelligent teenage boys as their central characters, and both are demanding rites-of-passage dramas. The great Alan Clarke directed Penda’s Fen while Red Shift was directed by John Mackenzie, better known for (among other things) The Long Good Friday (1980). Garner and Mackenzie collaborated on the screenplay for Red Shift which necessarily condenses the novel. I’d say it does this successfully but then I’ve read the book so may be too familiar with the story as a whole. Success or not, this is another remarkable piece of television drama which you can’t imagine being made today. But it is on YouTube, and for that we may be grateful. Watch it here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Children of the Stones

• Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin