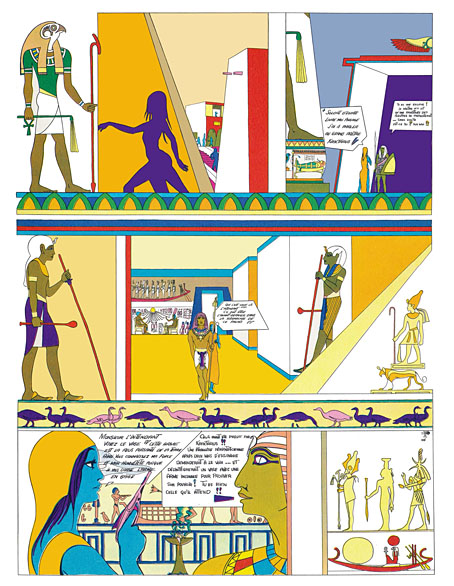

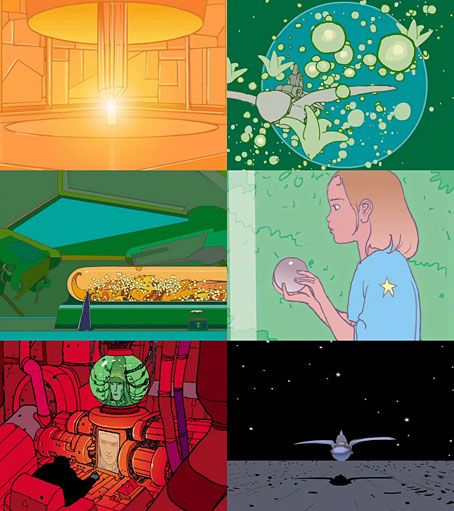

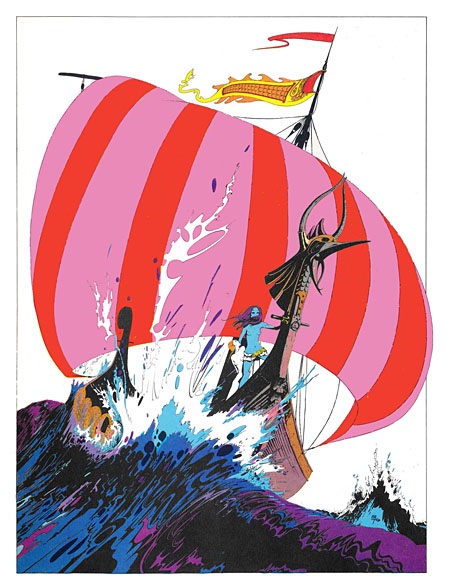

Saga est magnifique. Saga a la peau bleue. Saga est une extraterrestre. Envoyée par la reine de la planète Xam, la voici qui parcourt la Terre à plusieurs époques, traitées dans des styles différents. Son but: découvrir la quintessence artistique, politique et poétique de notre belle Terre. Marquée par l’Art nouveau, le psychédélisme américain, l’érotisme des années 1960 et la contreculture occidentale, Saga est une oeuvre hors norme et inclassable, dessinée sur des formats géants et publiée une première fois par Éric Losfeld en 1967. Hélas, le livre est très vite épuisé et devient un objet pour les collectionneurs. Cette édition reprend l’intégralité des planches de Saga, renumérisées et dotées d’une nouvelle mise en couleurs fidèle à l’originale. Saga peut enfin repartir dans une nouvelle… saga.

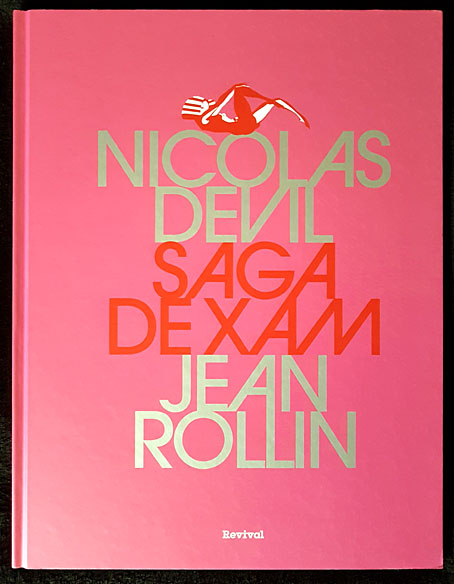

Here’s a book I never expected to see in a new edition. Saga de Xam is a 100-page bande dessinée depicting the time- and space-voyaging adventures of a blue-skinned alien woman, Saga, newly arrived on Earth from the planet Xam. The Xamians are a race of humanoid lesbians (their reproduction is parthenogenetic) whose planet is at war with the masculine Troggs; Saga has been sent to Earth to find a way to combat the Trogg invasion, an expedition that instructs her in the propensity of humans towards conflict and violence. The story was drawn by Nicolas Devil, with contributions from guest artists, and based on an outline by Jean Rollin which had been intended originally for a science-fiction film. There’s no need to go into detail about this cult item, I wrote about it at length several years ago after a couple of its pages stimulated my curiosity when they turned up in an exhibition catalogue. The book was published in 1967 by Éric Losfeld, an edition of 5000 which the publisher said he would never reprint, partly because of the expense, but also because he liked to think of the book becoming a rare object in the future. Rare it still is, although the embargo was broken in 1980, a year after Losfeld’s death, by the publication of a second edition. This was only a partial reprint, however, with a poor cover design and all the interior pages reproduced without their colour overlays.

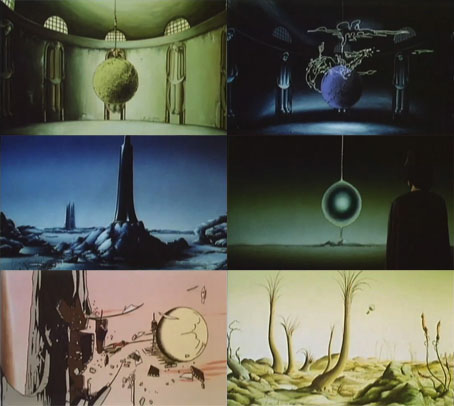

The new edition from Revival is slightly larger than the original (27.5 x 36 cm to the original 24 x 31 cm), and bound between heavy boards. A lengthy preface by Christian Staebler describes the book’s history, offering a few biographical details about Nicolas Deville (as he was known pre-1967), together with further information about the story’s creation. The wildness of the final pages is explained as an attempt by all involved to capture some of the delirium of an LSD trip, while also bringing the story of Saga’s investigation of the human race and its violent nature into the present day. Jean Rollin was apparently unhappy with this dénouement but I find the ending to be a satisfying one for a story where each chapter explores a different period of time (and of space, when Saga returns to her home planet).

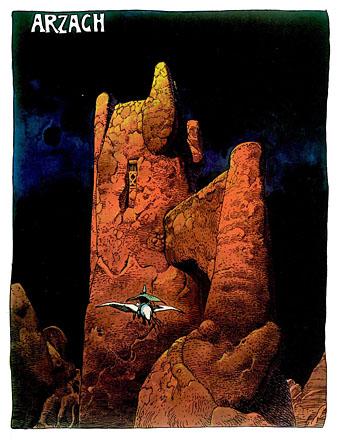

The icing on the cake is the appearance near the end of a few early drawings by Philippe Druillet, together with several beautiful pages by Devil, one of which found wider circulation when reprinted as a poster. The text in the new edition is still in French, of course, and even on slightly larger pages the legibility problem from the original remains. Devil was drawing on boards that were twice the size of their printed equivalents, without caring too much whether the story would be readable when scaled to a printable size. Losfeld’s solution was to provide a magnifying glass with each copy of the book. This isn’t too much of a problem; the story is easy enough to follow once you know the general outline, and for this story it’s the art that counts more than the words.