Q: Was the initial idea to be a music group?

Richard H. Kirk: I suppose that depends on how you define “music”. No, the initial idea was to be more of a sound group, just putting sounds together like jigsaw pieces. If the result did sound like music then it was purely coincidental.

From Cabaret Voltaire: The Art of the Sixth Sense (1984) by M Fish & D Hallberry

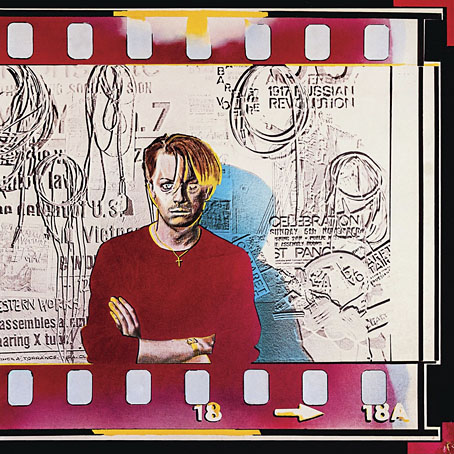

This was a shock, in part because I tend to think of certain artists as perpetually young even when I’ve been following them for decades. In the case of the not-so-young Cabaret Voltaire it was an easy frame of mind to slip into when Kirk and Mallinder were only photographically visible up to about 1990. After this the group resumed their former obscurity, cloaked by abstract images and Designers Republic graphics.

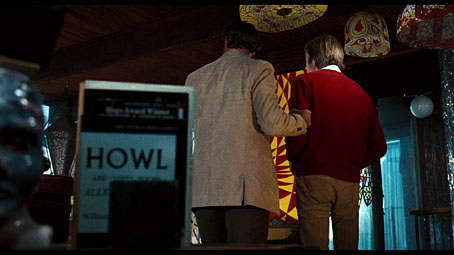

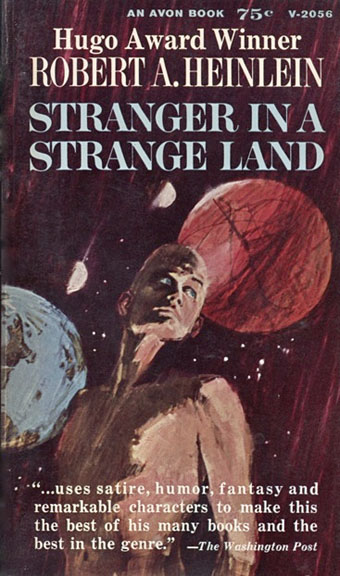

Oddly enough I’d been running through the early Cabs albums only a couple of weeks ago, and wondering how long Kirk was going to keep the revived group going on his own. I suppose this means that Cabaret Voltaire is now definitely finished, in which case it’s a double RIP. And just a few days ago I was reading a Mark Fisher essay on Joy Division, feeling as frustrated as I always do when Curtis and co. are praised for “channelling” (or whatever) the spirit of William Burroughs when nobody would think to connect Burroughs and Joy Division if you changed the title of the song Interzone to something else. Throbbing Gristle were closer to Burroughs personally than were Cabaret Voltaire but the influence on TG only became really overt when Industrial Records released Nothing Here Now But The Recordings, an album of Burroughs’ tape experiments. The Cabs were more important to me as a youthful reader of Burroughs’ novels for seeming to be broadcasting from inside his texts. Their early albums were disturbed and disturbing (a friend once asked me to switch off their music for this very reason), an unwholesome amalgam of dialogue taped from TV and radio, crude electronics, threatening voices, and songs that were warped into strange new shapes. “This is entertainment…this is fun…“ I’m still amazed that their first album included a cover of No Escape, a song by psychedelic group The Seeds, which didn’t sound out of place despite the weirdness surrounding it.

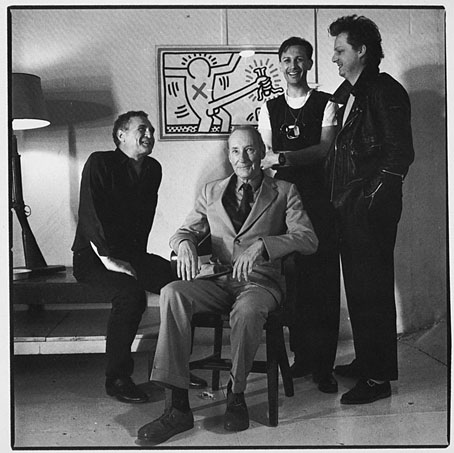

William smiles. Left to right: John Giorno, William Burroughs, Stephen Mallinder, Richard H. Kirk. Photo by Sylvia Plachy from the gatefold interior of A Diamond In The Mouth Of A Corpse (1985), a compilation album released by Giorno Poetry Systems.

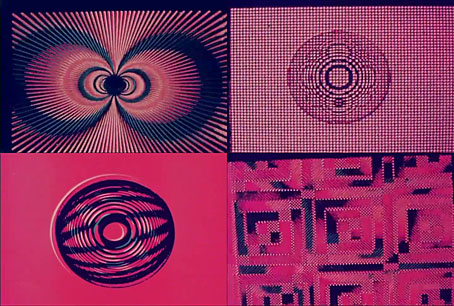

Cut-up theory was a constant in the Cabaret Voltaire discography, and in many of Richard Kirk’s solo recordings, with the group starting out as Dada-inspired tape collagists* before they found a way to present their experiments in a musical form. The concept is to the fore in the title of Cabaret Voltaire’s debut album, Mix-Up, and exemplified in the track that opens side two, Photophobia, a reworked version of a Surrealist monologue that dates from the group’s days making recordings in Chris Watson’s attic. Photophobia pulls you into the same queasy dreamspace in which you find yourself when reading Burroughs’ early cut-ups, a catalogue of oneiric splicings—”they’re injecting the rivers with stainless-steel fish…a coelacanth/a body with a shrunken head…”—the phrases being increasingly overwhelmed by rising synthesizer drones and Kirk’s squeaking clarinet. Kirk’s solo debut, Disposable Half-Truths, was a cassette-only release on Industrial Records infused with the Burroughs spirit in both technique and content, offering track titles such as Information Therapy and Insect Friends Of Allah. Cabaret Voltaire continually referred to Burroughs’ speculative essay collection The Electronic Revolution in interviews but it was Kirk who extended the group’s cut-up experiments to film and video. By 1982 they’d accumulated enough of their own video material to release a VHS collection on their own music and video label, Doublevision.

If I’ve concentrated on the early recordings it’s because the post-punk period continues to seem like a miraculous moment, a space of four years when anything was possible musically, a time when Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis could record an album as uncompromisingly strange as 3R4 then have it released on 4AD and sold in racks next to albums by label-mates Bauhaus and The Birthday Party. Cabaret Voltaire took advantage of this unique period to warp expectations in their own way, and to extend the boundaries of the possible. Richard H. Kirk’s subsequent career was prolific, releasing a blizzard of albums and singles under a variety of pseudonyms (Discogs lists 42 different Kirk aliases). One of my favourite pieces from his solo recordings is White Darkness from 1993, the last track on a 12-inch single, Digital Lifeforms, credited to Sandoz. There’s a mysterious quality here that I wish he’d explored more often on his later albums instead of letting the rhythms run their course for another seven or eight minutes. The sampled voice maintains a thread of continuity with Kirk’s music before and after, as does the reference to LSD in the Sandoz name, taking us back to Mix-Up and the mescaline experiments described on Heaven And Hell. Psychedelia by other means.

* For a taste of unadorned Cabs-related tape manipulation, see The Men With The Deadly Dreams, a cassette release compiled by Geoff Rushton/John Balance which features contributions from Chris Watson and Richard H. Kirk. Note that the blog post doesn’t give an accurate description of the tape contents.

• At Vinyl Factory: An introduction to Richard H. Kirk in 10 records.

• At The Wire: two interviews with Kirk from the magazine’s archives.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Recoil and Cabaret Voltaire

• Pow-Wow by Stephen Mallinder

• TV Wipeout revisited

• Doublevision Presents Cabaret Voltaire

• Just the ticket: Cabaret Voltaire

• European Rendezvous by CTI

• TV Wipeout

• Seven Songs by 23 Skidoo

• Elemental 7 by CTI

• The Crackdown by Cabaret Voltaire

• Neville Brody and Fetish Records