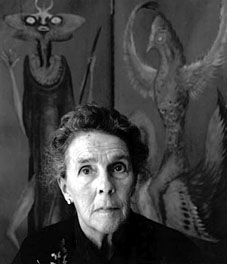

The Guardian profiles the wonderful Leonora Carrington, one of the last of the original Surrealists. There’s little excuse for the Tate’s neglect as recounted below, Marina Warner has championed her work for years and she was the subject of a TV documentary in the BBC’s Omnibus strand in the 1990s. Maybe the Tate curators should watch more television.

Leonora and me

Leonora Carrington ran off with Max Ernst, hung out with Picasso, fled the Nazis and escaped from a psychiatric hospital. Joanna Moorhead travels to Mexico to track down her long-lost cousin, one of Britain’s finest—and neglected—surrealists.

Joanna Moorhead

Tuesday January 2, 2007

The Guardian

A few months ago, I found myself next to a Mexican woman at a dinner party. I told her that my father’s cousin, whom I’d never met and knew little about, was an artist in Mexico City. “I don’t expect you’ve heard of her, though,” I said. “Her name is Leonora Carrington.”

The woman was taken aback. “Heard of her? My goodness, everyone in Mexico has heard of her. Leonora Carrington! She’s hugely famous. How can she be your cousin, and yet you know nothing about her?”

How indeed? At home, I looked her up, and found myself plunged into a world of mysterious and magical paintings. Dark canvases dominated by a large, sinister-looking house; strange and slightly menacing women, mostly tall and wearing big cloaks; ethereal figures, often captured in the process of changing from one form to another; faces within bodies; long, spindly fingers; horses, dogs and birds.

I remembered from childhood hearing stories about a cousin who had disappeared “to be an artist’s model”. But the truth was infinitely richer and more thrilling. Leonora Carrington, born into a bourgeois family, eloped at the age of 20 to live with the surrealist artist, Max Ernst (married, and some 20 years her senior). The couple fled across war-torn Europe in the late 1930s, and she later settled in Mexico, where she continued to paint, write and sculpt.

Most excitingly, though, Leonora was still alive – aged nearly 90 and living in a suburb of Mexico City with her husband, a Hungarian photographer. I contacted my Carrington cousins and discovered that one of them had visited her a couple of years ago: she was, he reported, on amazing form, and still working. I wrote to ask whether she’d be prepared to meet. Word came back that she would, and a few weeks later I flew to Mexico City.

Leonora Carrington looks eerily like my father – the same piercing eyes, the same trace of an upper-class English accent. We met at her house, and she led me through her dark dining room, crammed with her sculptures, to the kitchen where we were to spend most of the next three days, chatting endlessly over cups of Lipton’s tea (“I hardly touch alcohol,” she told me. “Enough people in our family have died of drink. Anyway I smoke, and it’s too much to drink and smoke.”)

Leonora was born in 1917, the only daughter (she had three brothers) of textile magnate Harold Carrington and his Irish wife, Maurie Moorhead, my grandfather’s older sister. Harold and Maurie were very different characters: where he was entrepreneurial, Protestant and a workaholic, Maurie was easy-going, Catholic and open-minded. The family home was an imposing mansion in Lancashire, Crookhey Hall – the sinister house that features in many of her paintings.

Leonora was expelled from three or four schools, but the one thing she did learn was a love of art. Her father was not keen on her going to art college, but her mother intervened and she was allowed to go and study in Florence. There, she was exposed to the Italian masters, whose love of gold, vermilion and earth colours were to inspire her later work.

She returned to England brimming with enthusiasm for the artist’s life, but her father had other ideas. As far as he was concerned, she had sown her wild oats and now needed to come back to earth. This meant launching her as a debutante: a ball was held in her honour at the Ritz, and she was presented to George V. A few years later, in a surreal short story The Debutante, she poured out her loathing of “the season”, with a witty description of sending a hyena along to take her place at her coming-out ball.

In 1936, the first surrealist exhibition opened in London – for Leonora, something of an epiphany. “I fell in love with Max [Ernst]’s paintings before I fell in love with Max,” she says. She met Ernst at a dinner party. “Our family weren’t cultured or intellectual – we were the good old bourgeoisie, after all,” she says. “From Max I had my education: I learned about art and literature. He taught me everything.”

Continues here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Surrealist cartomancy