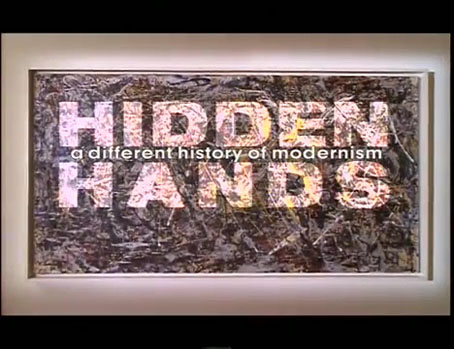

I thought I’d finished with the arts documentaries until I remembered this four-part series from 1995. Hidden Hands was based on researches by Frances Stonor Saunders who also co-produced. As the subtitle suggests, the programmes examined aspects of Modernist art and architecture that weren’t exactly unknown but were often downplayed (sometimes deliberately ignored) by the art establishment. The episodes were as follows:

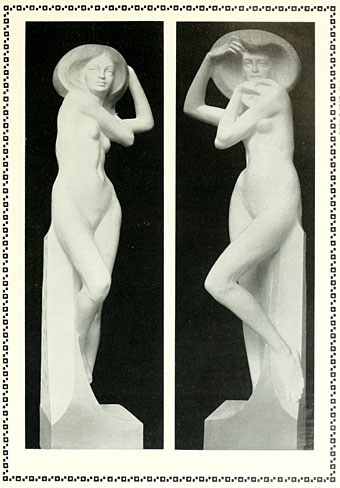

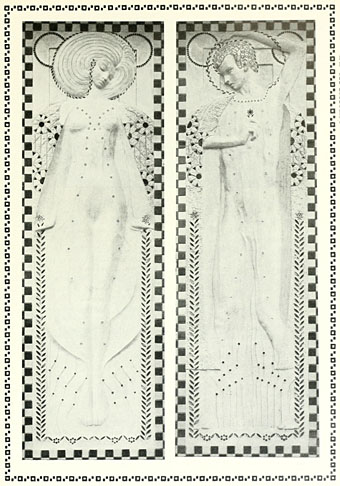

1: Is Anybody There? The occult roots of abstract painting, especially the influence of Theosophy on Vasily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. Kazimir Malevich and Frantisek Kupka are also mentioned at the beginning of the programme but we don’t hear anything more about them.

2: Art and the CIA. A history of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA front for channelling money to avant-garde exhibitions and literary magazines during the Cold War.

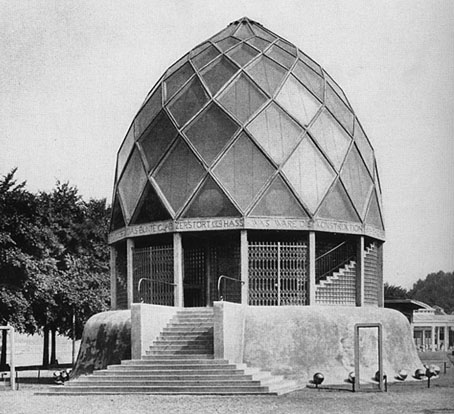

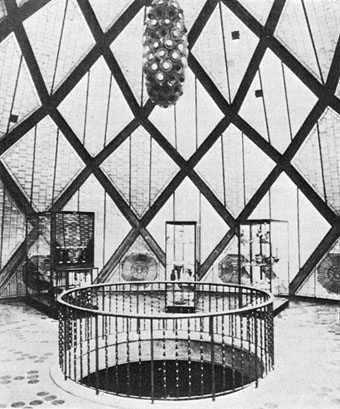

3: A Clean White World. Modernist architecture as a reaction to, and proposed solution for, the squalor of 19th-century city life. Also the similarity between the impulses that drove the Modernist architectural ideal, and the later health and purity obsessions of European fascist states.

4: Painting with the Enemy. The inadvertent way in which the animus towards “degenerate art” shared by the Nazis and the Vichy regime in occupied France helped sustain Modernism during the war years.

This is a very good series on the whole, informative and with a roster of authoritative interviewees. The narration overstates the contrarian angle in places but that’s television for you. Much of the history under investigation wasn’t necessarily hidden, more sidestepped by general discussions of 20th-century art. Even so, fifteen years earlier in the architecture episode of The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes covered similar territory and with similar criticisms, following the development of what would become known as the International Style while noting Mussolini’s adoption of a Modernist idiom for the architecture of Fascist Italy.

Elsewhere, when Hughes reviewed a major Kandinsky retrospective he paid sufficient attention to Kandinsky’s Theosophical beliefs; this was in 1982 for TIME magazine, not exactly an obscure publication. Theosophy’s ectoplasmic tentacles are all over the art of the late 19th century so you’d expect some crossover into the art of the new century, as there was in the careers of the artists themselves. (Matisse was a pupil of Gustave Moreau, for example, an inconvenient detail that often irritated critics.) Given the amount of artists swayed by Madame Blavatsky’s writings, a more interesting argument might have been to propose Theosophy as the prime cause of early abstraction rather than another inconvenient factor in its development. Hilma af Klint’s pioneering abstract paintings were as much products of her Theosophical studies as were those of Kandinsky but in the 1990s nobody was paying her very much attention.

Mondrian’s mysticism: Evolution (1910–1911).

As for the CIA, the agency’s clandestine cultural adventures were exposed by a leak in the late 1960s—Stephen Spender famously resigned in shame from his editorship of Encounter magazine—so this could almost be classed as old news. What you wouldn’t have had in the past, however, is the agents involved in the scheme openly discussing their activities.

Continue reading “Hidden Hands: A Different History of Modernism”