A couple of Halloweens ago I worked my way through a blu-ray box of the horror films made by Universal Studios in the 1930s and 40s. It was a fun and instructive experience: fun because I’d not watched many of the films properly for a long time; instructive for reaffirming my dislike of Tod Browning’s Dracula, a film so inert and lacking in cinematic drama it may as well be a series of still pictures. Browning’s film is further diminished when you have the opportunity to watch James Whale’s Frankenstein films immediately after it. The collection also allowed me to compare the BFI release of Universal’s silent version of The Phantom of the Opera, where Lon Chaney is an unforgettable Phantom, with the 1943 remake, a film I didn’t recall having seen before. The only positive things about the remake are the always worthwhile Claude Rains, even if he is wasted in the Phantom role, and seeing the massive Paris Opera House set from the silent version being reused.

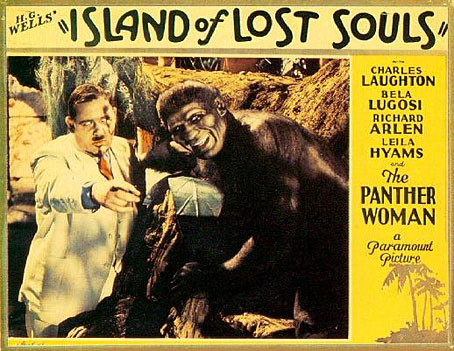

The differences between the Universal adaptations of Dracula and Frankenstein are noted in Kevin Brownlow’s 90-minute documentary which is an extra on the Frankenstein disc. Brownlow’s film, which was originally made for TV in 1998, charts the evolution of Universal’s horror films from their roots in silent cinema and German Expressionism up to the 1940s when the cycle deteriorated into sequelitis and self-mockery via Abbott and Costello. “Universal” here may be taken as referring to all of Hollywood’s early horror films. Rather than waste time on the studio’s increasingly inferior sequels, rival productions from other studios are briefly discussed: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Paramount), The Island of Lost Souls (Paramount), King Kong (RKO), and Mystery of the Wax Museum (Warner Brothers). In doing this Universal Horror follows the template that Brownlow established with fellow film historian David Gill in 1980 when they produced Hollywood for Thames TV, a 13-part series about the birth of American cinema which I rate as the best documentary series about film ever made. (Gill died in 1997 so Universal Horror is dedicated to his memory.) Hollywood interviewed as many people as possible connected with the production of the first silent films, following the format of the landmark The World at War (1973) series which related the events of the Second World War in 26 hour-long episodes. The World at War was narrated by Laurence Olivier; for Hollywood Brownlow & Gill had James Mason, not only an equivalent voice of authority but also a man with a great enthusiasm for silent cinema. Subsequent Brownlow & Gill documentaries had Lindsay Anderson as narrator, another silents enthusiast with a similar gravitas in his narrative delivery. The narrator of Universal Horror, Kenneth Branagh, isn’t bad as such but whatever his qualities as an actor, his voice alone is a poor match for these heavyweights. He does at least seem to have controlled the sporadic squeaks which mar his delivery in an earlier Brownlow & Gill series, Cinema Europe: The Other Hollywood (1995).

Universal Horror and Cinema Europe both fall short when compared to Hollywood by being made too late. By the 1990s most of the men connected with the early years of European cinema had died, and so had many of the actors who made the Universal films. It’s left to a handful of survivors, most of whom are women, to remember the days of their youth: Nina Foch (The Return of the Vampire), Gloria Stuart (The Invisible Man), Fay Wray (who must have spent most of her later years repeating stories about King Kong but here also discusses her role in Mystery of the Wax Museum), Lupita Tovar (the Spanish-language Dracula), Turhan Bey (The Mummy’s Tomb), Rose Hobart (Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde), and Curt Siodmak (The Wolf Man). Additional commentary is provided by the daughters of significant figures: Sara Karloff, Carla Laemmle (who has a cameo in Dracula) and Arianne Ulmer whose father, Edgar G. Ulmer, directed The Black Cat for Universal, a much better film than the 1943 Phantom of the Opera, and one which should have been in the box set instead. Lastly, there’s some outsider commentary by Ray Bradbury (who also appeared in Brownlow’s next documentary, Lon Chaney: A Thousand Faces), Gavin Lambert, James Karen, Forrest J. Ackerman, Curtis Harrington, James Curtis (author of James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters), and David J. Skal (author of Hollywood Gothic, The Monster Show, etc). Given the breadth of the subject—two decades of film history—this should have been a series like Cinema Europe, but horror on the page or on the screen remains the most abject of the genres, continually marginalised, complained about, ignored, censored, banned. Ninety minutes of documentary time is often as good as it gets, especially with Kevin Brownlow producing.

Universal Horror at the time of writing is available for viewing at the Internet Archive, waiting for Universal’s legal goons to put a stake through its heart. Someone has also uploaded the whole of Brownlow & Gill’s Hollywood series which is gratifying to see. The latter is scattered around YouTube in varying quality so it’s good to have a range of options. It’s essential viewing wherever you see it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Illustrating Dracula

• Illustrating Frankenstein

• Psychotronic Video

• Dracula and I by Christopher Lee

• Nightmare: The Birth of Horror

• Rex Ingram’s The Magician

• The Mask of Fu Manchu