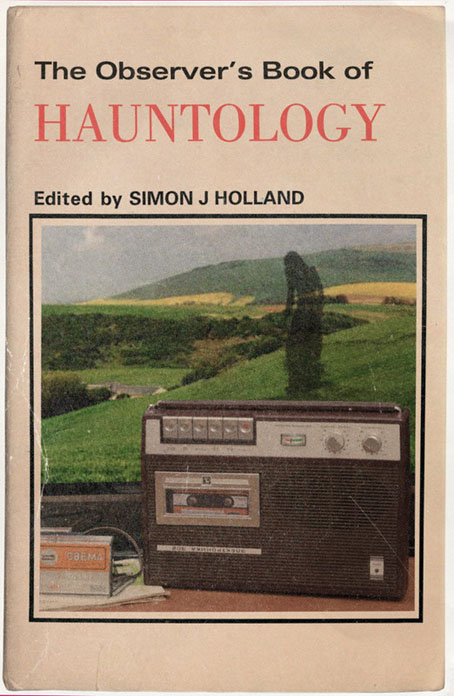

An invented book cover from the latest post at blissblog. Since I like fakes of this nature, especially when they’re carefully done, I had to go in search of the creator. Rachel Laine is the person responsible, and there’s more along these lines at her Flickr pages, together with many similar items from the universe next door. (I know someone who’ll appreciate all those faded magazine covers combining soft-porn photos with headlines for stories about analogue synths.) Another of the book covers is a guide to “Witches and Witch Craft”, a title whose real-life counterparts included books such as the Hamlyn guide to witchcraft and black magic from 1971. As I’m often saying, the 1970s was the witchiest decade of the 20th century.

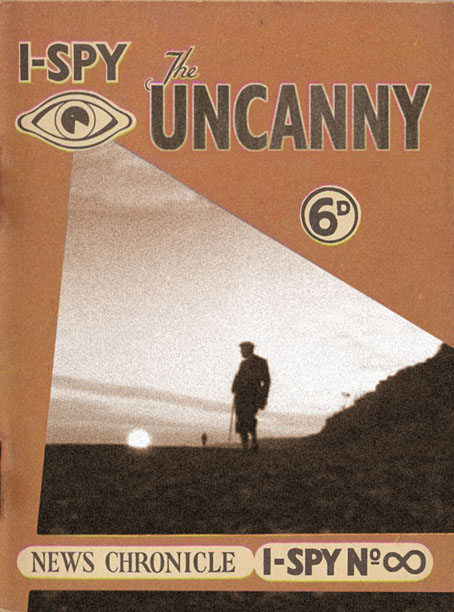

All of which reminded me of a couple of recent inventions of my own. One of the advantages of writing here is that I can retrieve from obscurity some of the things I’d previously cast into the Malebolge formerly known as Twitter. This impromptu creation is something I threw together after Callum J posted the cover of an old I-Spy book dedicated to “The Unusual”. (If you don’t know what the I-Spy books were—and still are—Wikipedia has the history.) The screen-grab from Whistle and I’ll Come to You is a lazy choice but I wanted to surprise Callum by reworking his cover as quickly as possible.

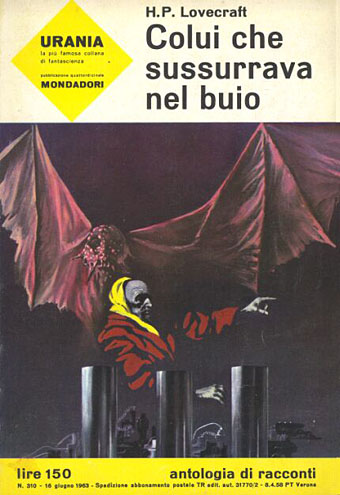

A little more considered is this proposal for a set of British postage stamps dedicated to Nigel Kneale and his works. This one came about after a comment from Kim Newman that such a thing was overdue from the Royal Mail. Since I agreed I thought I could at least fake them into existence. They’re still a little incomplete—actual stamps would have a mention of Kneale on each one—but they look plausible. The artwork was swiped from a series of Quatermass book covers created by the prolific Karel Thole for Mondadori in the late 1970s. The images for the first Quatermass and Quatermass and the Pit work very well, I think, the fourth one less so. If I was doing these myself I’d try some combination of a radio telescope and a stone circle. Windows into another world; in the universe next door Quatermass is bigger than Star Wars. But we live here, not there.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Disciples of the Scorpion

• Ghost Box and The Infinity Box

• Llewellyn occult magazine and book catalogue, 1971

• Typefaces of the occult revival

• The Book of the Lost

• Books Borges never wrote

• Forbidden volumes