Among recent DVD releases there’s a handful worth noting here. First up is another great collection of rare cinema from the Center for Visual Music, 3 Films by Elias Romero.

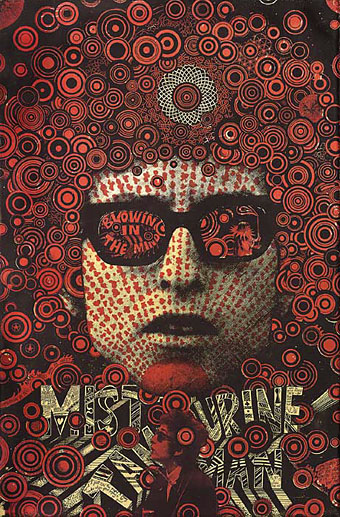

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.

Judex.

It was just over a year ago that I asked “how long do we have to wait for a Judex DVD?” and once again the DVD gods seem to have been listening. Eureka Video’s excellent Masters of Cinema series has paired Franju’s 1963 film with his other Feuillade-inspired work, Nuits rouges.

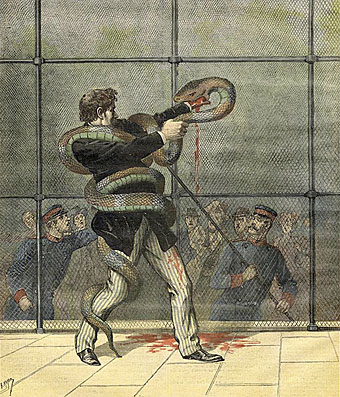

The magical, rarely seen Judex – directed by the great Georges Franju (Eyes Without a Face) – was largely unappreciated at the time of its release in 1963. This lyrical and dreamlike picture, a putative “remake” of Louis Feuillade’s own 1916 Judex, is as evocative of the silent master’s own works as it is the later films of Jean Cocteau and Salvador Dalí. A French reviewer wrote in 1963: “The whole of Judex reminds us that film is a privileged medium for the expression of poetic magic”. Starring the magician Channing Pollock, the divine Edith Scob, and the mesmerising Francine Bergé, Judex concerns a wicked banker, his helpless daughter, and a mysterious avenger. It plays like a fairy tale – one in which Franju creates a dazzling clash between good and evil, eschewing interest in the psychological aspects of his characters for unexplained twists and turns in the action. The beautifully controlled imagery, superbly rendered by Marcel Fradetal’s black-against-white photography, animates a natural world and the spirits of animals all at war with a host of diabolical forces. Franju’s Judex and Nuits rouges both paid overt homage to the surreal, silent serial-works of Feuillade. Scripted in collaboration with Feuillade’s grandson – Jacques Champreux – these films evince the same poetic magic that made the art of that earlier master a cause célèbre not only for the Surrealist movement, but also for the world-renowned Cinémathèque Française. It was the Cinémathèque (co-founded by the legendary Henri Langlois with Franju) that helped resurrect the reputation of Feuillade decades after he’d slipped out of the public consciousness.

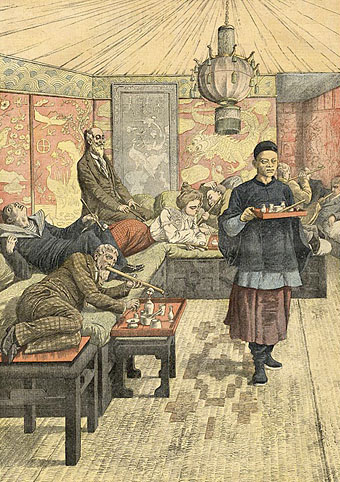

Nuits rouges [Red Nights] – released in the UK as Shadowman – was the second Franju-Champreux meditation upon the films of Feuillade. It aggressively escalates a pulp atmosphere steeped in shocking turns of events to an even more vertiginous level. Here, the object of pursuit is the fabled treasure of the mythical order of the Knights Templar – which the filmmakers use as the jump-off point for staging a series of fantastic set-pieces. As the Fantômas-esque arch-criminal (known only as “The Man Without a Face”, played by Jacques Champreux himself) violently pursues the treasure, the action intensifies amongst a cadre of post-’68 bohemians, the Paris police bureau, and a cult of cowled conspirators. The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present Georges Franju’s two most mindbending films on DVD in the UK for the first time. —Special Features— Gorgeous new transfers in their original aspect ratios—New and improved English subtitle translations—Video interviews, for both films, by Franju-collaborator Jacques Champreux—40-page booklet containing newly translated interviews with Georges Franju; newly translated writing by Jacques Rivette, and more!

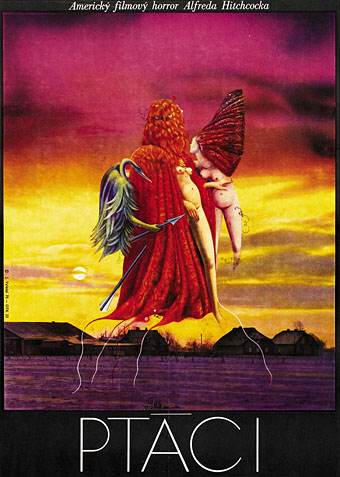

Vampyr.

Eureka’s site seems to be lacking a page for Judex (unless I missed it) but they do have a page for Carl Dreyer’s atmospheric, oneiric and weird-in-all-senses-of-the-word Vampyr (1932), which is receiving a decent UK release at last. This was one of the films I reviewed in 2006 for the André Deutsch book of horror cinema and my own DVD is a very shoddy import copy which I’ll be happy to replace.

The first sound-film by one of the greatest of all filmmakers, Vampyr offers a sensual immediacy that few, if any, works of cinema can claim to match. Legendary director Carl Theodor Dreyer leads the viewer, as though guided in a trance, through a realm akin to a waking-dream, a zone positioned somewhere between reality and the supernatural.

Traveller Allan Gray (arrestingly depicted by Julian West, aka the secretive real-life Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg) arrives at a countryside inn seemingly beckoned by haunted forces. His growing acquaintance with the family who reside there soon opens up a network of uncanny associations between the dead and the living, of ghostly lore and demonology, which pull Gray ever deeper into an unsettling, and upsetting, mystery. At its core: troubled Gisèle, chaste daughter and sexual incarnation, portrayed by the great, cursed Sybille Schmitz (Diary of a Lost Girl, and inspiration for Fassbinder’s Veronika Voss.) Before the candles of Vampyr exhaust themselves, Allan Gray and the viewer alike come eye-to-eye with Fate — in the face of dear dying Sybille, in the blasphemed bodies of horrific bat-men, in the charged and mortal act of asphyxiation — eye-to-eye, then, with Death — the supreme vampire.

Deemed by Alfred Hitchcock ‘the only film worth watching… twice’, Vampyr’s influence has become, by now, incalculable. Long out of circulation in an acceptable transfer, The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present Dreyer’s truly terrifying film in its restored form for the first time in the UK.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Judex, from Feuillade to Franju

• Fantômas

• Hail, horrors! hail, infernal world!

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.

Elias Romero is considered to be the Grandfather of the Light Show. In San Francisco in 1956 he began developing a performance medium using overhead projectors. He mixed oils and inks in dishes placed on the projectors, passing light through the translucent blend which was then projected onto a screen. He performed hundreds of shows throughout California, accompanied by musicians and performers. Many of the later psychedelic light show artists were inspired by his work. In 1969 he met Richard Edlund (camera), and they began making films with Bill Spencer (music) and others. Stepping Stones (33 mins) – Abstract drama played out in light, color and sound – is made up entirely of original vintage light show projections, excerpts of which were featured in the 2005 Visual Music exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Za (24 mins) – An intense and illuminating episode of consciousness unfolding, features projections onto Diane Varsi as poet and alchemist, and costumes by Cameron. Lapis Lazuli, (29 mins) – Mystical transformation, music and poetry, with Bill Fortinberry and Susan Darby, shows them meeting simultaneously on different myth-planes. The DVD Bonus Features include: “Notes on 3 Films” – a Documentary with interviews with Elias Romero and Edlund, and a Gallery featuring other artwork by Romero. NTSC, Region 1. TRT approx 2 hours.