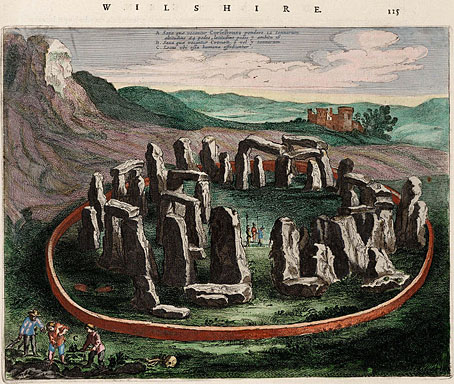

Wiltonia sive Comitatus Wiltoniensis; Anglice Wilshire (1649) by Atlas van Loon.

Avebury doth as much exceed Stonehenge in grandeur as a Cathedral doth an ordinary Parish Church.

John Aubrey

John Aubrey (1626–1697) was the pioneering antiquarian and archaeologist whose interest in the ancient sites of southern England made him the first person to subject Avebury to any serious study. As a consequence his comparison between Avebury and Stonehenge may contain some bias—Stonehenge’s site on the desolate Salisbury Plain made its presence well-known even if it was little understood—but it should be noted that in Aubrey’s time there were more stones at Avebury than there are today, and the long avenues leading to and from the outer circle were still intact. The stones of Avebury were unfortunately small enough to be broken up by the locals for building materials.

Stonehenge (1835) by John Constable.

The size of the stones, and the isolation of the site explains why Stonehenge has proved more attractive to the arts than other Neolithic monuments. William Macready in the 19th century added Stonehenge-like trilithons to his stage designs for King Lear, an addition that persisted for decades; Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) famously ends with a scene at the stones, while in the 20th century Stonehenge was shoehorned into Night of the Demon (1957), Jacques Tourneur and Charles Bennett’s film adaptation of Casting the Runes by MR James. James was an antiquarian himself so may well have approved of the inclusion, especially the way the stones are used in the opening scene.

Stonehenge at Sunset (1835) by John Constable.

Painted renderings of the stones tend to be a mixture of archaeological studies and depictions like those featured here. The site had an understandable attraction to the Romantics, and drew both Constable and Turner there. (See Turner’s paintings and sketches here.) Constable’s watercolour of the stones against a turbulent sky is oft-reproduced. Some of the stones seen in 19th paintings and drawings lean more than they do today, having been restored to the vertical in the 20th century.

Stonehenge – Twilight (c. 1840) by William Turner of Oxford (not to be confused with his more famous namesake).

Closer to our own time there’s Henry Moore’s marvellous series of lithograph prints from 1973 which study the stones from a variety of angles. These include close views, something few other artists seem to attempt. The photo print below shows the site as it was in the 1890s with cart tracks passing nearer to the stones than visitors today are allowed to venture.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Stonehenge

• Stonehenge panorama