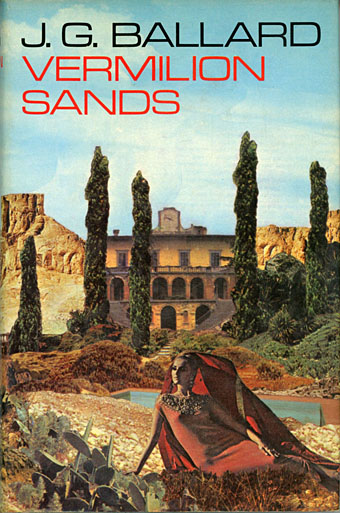

First UK edition, 1971. Art by Brian Knight.

Vermilion Sands (1971) is a story collection by JG Ballard which maintains a cult reputation despite being overshadowed by its author’s more popular (and notorious) novels. Most of the stories were written in the 1960s—a couple of them are among Ballard’s earliest works—but where many of his other short stories can read like the work of a writer with bills to pay, the tales of Vermilion Sands are much closer to Ballard’s core interests, filled with symbolic resonance and literary allusion.

Vermilion Sands, the place, is a near-future resort with a desert climate and an unspecified location; a locale where the Côte d’Azur meets Southern California but the ocean is a sea of sand. While each story has a different artistic or cultural theme, all the stories are populated by the idle midde-class types found in the rest of Ballard’s work. Ballard was more receptive to visual art, especially painting, than many authors, particularly the SF writers of his generation for whom art was less interesting than science and technology. There is science and technology in these stories (some of the latter is now inevitably dated) but it doesn’t dominate the proceedings. The stories derive less from scientific speculation than from Ballard’s desire to create a future he would have been happy to inhabit himself, an alternative to the grim dystopias which proliferate in science fiction. The background furnishings also reflect the author’s ideal, owing much to the Surrealist landscapes of Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst, a pair of artists whose works are often referenced in Ballard’s fiction. Given all of this you’d expect that cover artists might have risen to the challenge more than they have. What follows is a look at the most notable attempts to depict Vermilion Sands or its population, only a few of which are covers for the book itself.