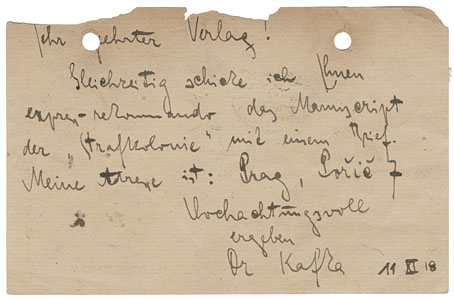

Tulips Shall Grow (1942).

Film producer George Pal‘s run of fantasy and science fiction films are justly celebrated and include one particular favourite of mine, The Time Machine (1960). Prior to the 1950s, however, Pal was known for his distinctive animations using wooden puppets, a technique which acquired several names, Pal Doll, Madcap Models and Puppetoons. Europa Film Treasures has two choice examples of these, La Grande Revue Philips from 1938, a promotional work for the Dutch radio company, and Tulips Shall Grow, a striking piece of wartime propaganda from 1942. The latter is especially worth a watch, not least for the way its scenes of destruction prefigure similar scenes in Pal’s updating of War of the Worlds ten years later.

The few Puppetoons I’ve seen have a unique atmosphere, the brightly-lit wooden characters seem hyper-real, like computer graphics decades before their time, while the movement tends to be bouncy and repetitive due to the figures having a limited range of poses. The only animation I can think of with a similar quality—and which may well have been influenced by Pal’s work—is Inspiration, Karel Zeman’s animation of glass figures from 1949. Some of Pal’s later films used his Puppetoon technique, notably tom thumb (1958), a film which also featured Jessie Matthews (aka Mrs Lord Horror in David Britton’s mythos) in one of her last screen appearances.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Karel Zeman

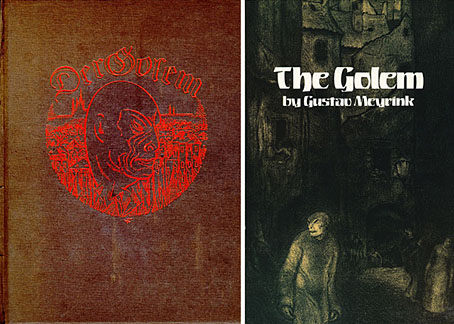

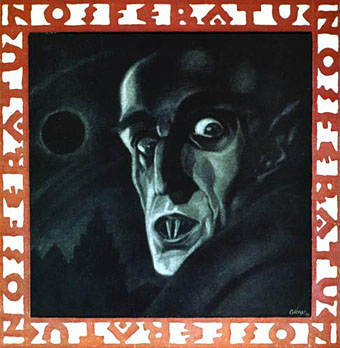

• Barta’s Golem