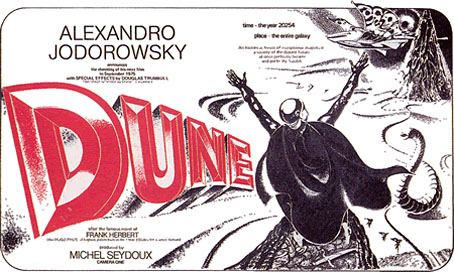

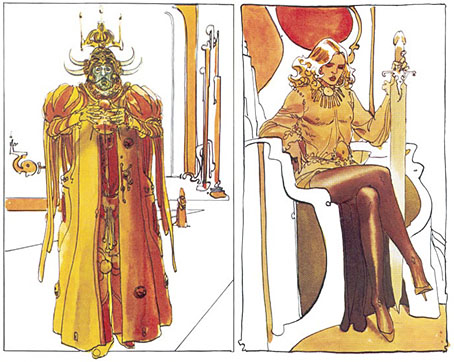

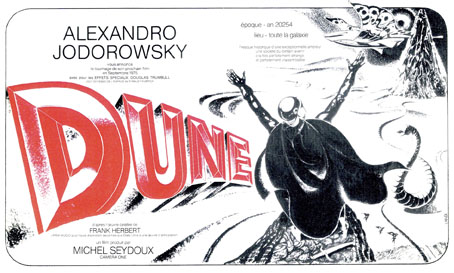

French poster by Michel Landi for the ill-fated Jodorowsky film.

There’s more to French music than Air and Daft Punk, and there’s more to cosmic French music than Magma, although you wouldn’t always know it to read Anglophone music journalists. I’ve been championing the electronica recorded by Bernard Szajner for a long time, and even tried without success to get one of his albums reissued a few years ago. (Which reminds me: Gav, you’ve still got my Szajner albums!) That album (credited to “Zed”), Visions Of Dune (1979), has been out-of-print since 1999 so it’s good to know it’s being reissued on vinyl and CD next month by Finders Keepers’ Andy Votel. FACT has a mix of extracts to give the curious some idea of its buzzing analogue soundscapes.

Visions Of Dune (1979) by Zed (Bernard Szajner). Artwork by Klaus Blasquiz.

Visions Of Dune attempts to illustrate Frank Herbert’s novel in musical form; you wouldn’t really know this without the track titles but that’s the way it often is with instrumental music. The album has gained a surprising cult reputation in recent years although it’s difficult to tell whether this is merely a consequence of its rarity or whether it’s because people like Carl Craig have taken to listing it as a favourite electronic record. It’s a decent enough album but I’ve always preferred Szjaner’s follow-up, Some Deaths Take Forever (1980), a conceptual polemic against the death penalty which is ferocious enough in places to be classed among the post-punk electronica being produced in the same year by Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire. Szajner later recorded an album with Howard Devoto, Brute Reason (1983), which puts him even more firmly in the post-punk camp. I suspect Some Deaths… offends the hardcore synth-heads with its squalls of electric guitar and other traces of the rock milieu. More amenable is another Szajner album, Superficial Music (1981), which remixes the Visions Of Dune tracks into seven chunks of doom-laden ambience. I’ve never thought of the resulting sound as very superficial, “unsettling” is closer to the mark which is why I included an extract in my Halloween mix last year.

Chronolyse (1978) by Richard Pinhas. Artwork by Patrick Jelin.

Visions Of Dune isn’t the only Dune-related synth album from France. Chronolyse (1978) is the second solo album by Richard Pinhas, another musician you won’t find many Brit writers discussing even though he’s been recording since 1974. Pinhas’s inspirations are an unusual amalgam of science fiction and contemporary French philosophy, a subject he studied at the Sorbonne; prior to going solo he was performing with Heldon, a French prog band whose name is taken from Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream. Heldon may be classed as a prog group but their first album, Electronique Guerilla (1974), has one side dedicated to William Burroughs, features a track with “lyrics by Nietzsche”, and also contains an appearance by Gilles Deleuze. Deleuze and Norman Spinrad appeared on later Pinhas solo albums although neither of them are on Chronolyse which, like Visions of Dune, is a wordless (and often tuneless) meander through synthesised soundscapes named after Dune characters. The music on the first side is much more sparse than Szajner’s, and less satisfying as a result; the second side improves with the 29-minute Paul Atreïdes, a typical Pinhas guitar-and-synth jam with extended Fripp-like soloing. As with Szajner, all the Heldon/Pinhas output tends towards the abrasive, and looking at the recent Pinhas discography the man is showing no sign of growing soft, having played shows recently with notorious noise merchants Merzbow and Wolf Eyes.

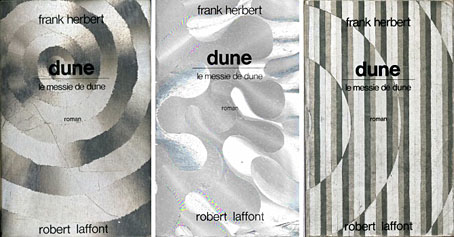

Dune paperbacks from Robert Laffont (1975–1983). Designer unknown.

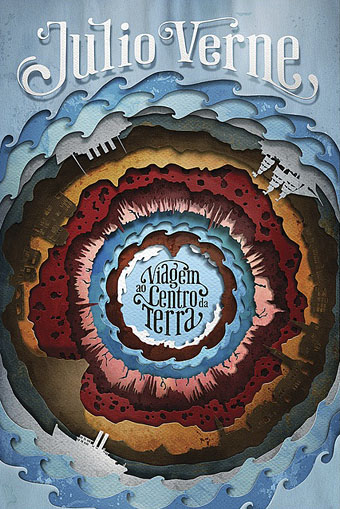

Has there been any other Dune-related music from France? Given the French enthusiasm for science fiction I wouldn’t be surprised. A search for French covers of Frank Herbert’s novels turned up these strikingly abstract examples from Robert Laffont which I’d not seen before. That combination of foil backing and lower-case Helvetica is clearly derived from the celebrated Prospective 21e Siècle series of new music albums released by Philips in the late 1960s. Many of those albums featured exclusive recordings of musique concrète or electro-acoustic compositions (and many of them featured French composers) so there’s another electronica connection. Incidentally, if you ever find one of those Philips albums going cheap in a shop, buy it! The series is very collectible and some of them command high prices. Even if you don’t like the music, they’re worth having for the shiny sleeves.

Update: Further investigation reveals another French album with Dune connections, Eros (1981) by Dün, a Magma-like band whose name is taken from Herbert’s novel. So too are some of the track titles on their sole release: L’Epice and Arrakis.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune