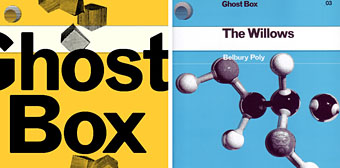

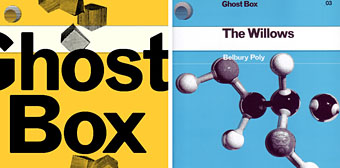

Q: What do you get when you cross analogue synthesizers, samples from obscure public information films, the graphic design of Pelican Books, Arthur Machen, HP Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, CS Lewis, Hammer horror, the Wicker Man and the music from Oliver Postgate’s animated films for children?

A: the CD releases by artists on the Ghost Box label. Ghost Box describe themselves as “an independent music label for artists that find inspiration in library music albums, folklore, vintage electronics, and the school music room” which, if you’re familiar with the reference points, is exactly what you get. A rather wonderful blend it is too, some of the tracks on Belbury Poly’s The Willows (named after Algernon Blackwood’s stunning horror tale) are how I expected Stereolab to sound until I heard them and was rather disappointed.

Favourite of the Ghost Box releases I’ve heard to date is (perhaps inevitably) Ourobourindra by Eric Zann (the “artist” here is named after Lovecraft’s haunted musician from The Music of Erich Zann). The website description—”Eric Zann’s radios, oscillators and recordings conjure eldritch, echoing spaces and invoke the voices of the dead that whisper within them”—again is a pretty accurate summation of this atmospheric and sinister audio collage. “Sinister” is a term that can be applied to much of this music and the Ghost Box founders, Julian House and Jim Jupp, declare in a Wire feature this month that matters spectral are of particular concern, hence the label name. Ourobourindra works especially well in this regard, sounding like the product of someone working through a trauma caused by viewing the seance scene from Dracula AD 1972 at too young an age. This is one I’ll be playing on Halloween.

Ghost Box music can be purchased online here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

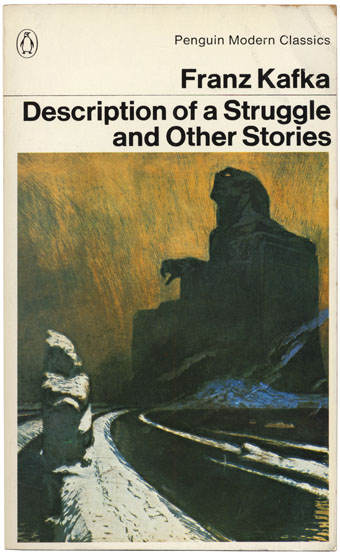

• Penguin book covers

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• The music of the Wicker Man

• The Absolute Elsewhere