Against the tide

| Jon Savage remembers Derek Jarman.

Tag: Derek Jarman

Michelangelo Antonioni, 1912–2007

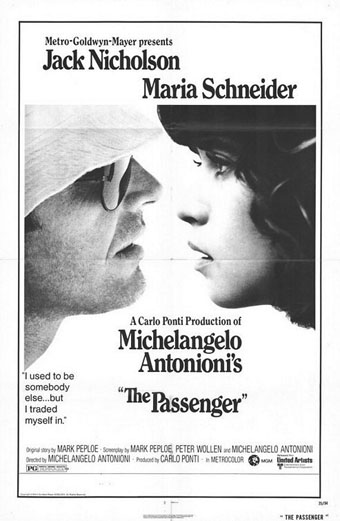

Another one bites the dust… What are the odds against two of the last surviving big names of cinema expiring in the same week? I could never get fully behind Antonioni the way I could with Bergman, I didn’t think much of the Neo-Realist school that Antonioni began as a member of while later films such as L’Avventura seemed like empty stylistic exercises. He divided opinion even among his peers—Orson Welles couldn’t bear his work whereas Stanley Kubrick put La Notte in a “ten best” list in 1963. I always enjoyed Blow-up (1966) even though it seems fatuous next to Performance while Zabriskie Point (1970) is a joke. But I like The Passenger (aka Professione: Reporter, 1975) very much.

A simple story—reporter in the Sahara swaps identities with a dead arms dealer then goes on the run—featured Jack Nicholson giving one of his last good performances before his descent into gurning self-parody. Also Ian Hendry, Steven Berkoff (between Kubrick films) and Jenny Runacre shortly before she was in Jubilee for Derek Jarman. The film works as an extended travelogue, ranging from Africa to England then into Spain as Nicholson’s character picks up student Maria Schneider on his travels and is pursued by his wife (who doesn’t believe he’s dead) and men intent on killing him. Events are resolved during a celebrated seven-minute single take where the camera passes miraculously through the iron bars of a hotel window. One of Antonioni’s finest qualities was his appreciation of architectural and cinematic space and the final shot of the film is a perfect example of this. The Passenger was out of circulation for years but is now available on DVD.

• Guardian obituary | David Thomson appreciation

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Further Back and Faster

Fred Holland Day

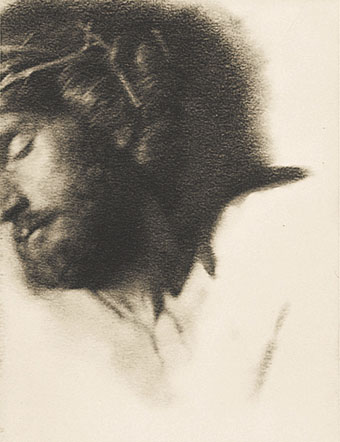

The Seven Words: “It is finished!” (1912).

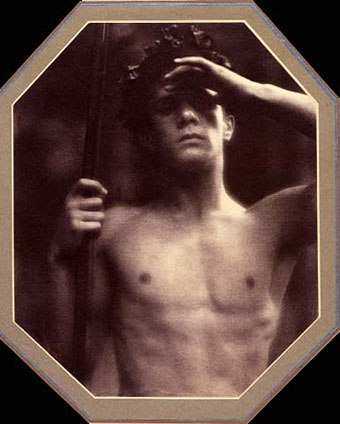

Photographer and publisher Fred Holland Day (1864–1933) enjoyed the iconography of Easter enough to stage his own crucifixion tableau with friends, as well as producing a series of seven pictures based on Christ’s last words, of which the final poignant number is shown above. His 1898 crucifixion is homoerotic enough it might still cause a stir among today’s gay-hating cross-wavers if they saw it, and he had the audacity to play the part of Christ himself.

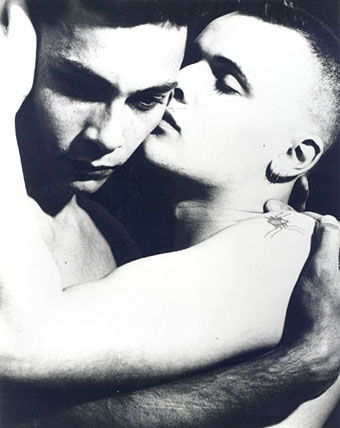

No surprise, then, that he also enjoyed photographing the unclothed bodies of young men which caused some controversy at the time. The examples of his pictures below display the same ritualistic qualities seen in some of Derek Jarman‘s films, especially the more formal compositions of The Angelic Conversation. I’ve never seen any acknowledgment of Day’s work from Jarman but, given that they both concerned themselves with Saint Sebastian, I’d be surprised if he wasn’t at least aware of these pictures.

Suffering the Ideal (no date).

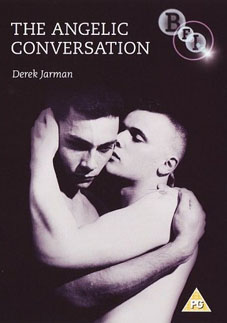

The Angelic Conversation

Title by John Dee, words by William Shakespeare, narration by Judi Dench and music by Coil; Derek Jarman’s oneiric film/poem is released on DVD, along with two other works.

The BFI releases three Derek Jarman films together—Caravaggio (1986), Wittgenstein (1993) and The Angelic Conversation (1985)—all digitally restored and re-mastered for DVD and each with extensive and illuminating extra features.

The films were made with the BFI Production Board, whose aim was to foster innovation in British filmmaking, thus providing a natural home for Jarman’s artistic sensibility. These three films represent highpoints in his career and are perhaps the most enduring in their appeal and relevance to contemporary audiences.

Intense, dreamlike, and poetic, The Angelic Conversation is one of the most artistic of Derek Jarman’s films. With his painter’s eye, Jarman conjured, in a beautiful palette of light, colour and texture, an evocative and radical visualisation of Shakespeare’s love poems.

Of the 154 sonnets written by Shakespeare, most were written to an unnamed young man, commonly referred to as the Fair Youth. Here, Judi Dench’s emotive readings of 14 sonnets are coupled with ethereal sequences; figures on seashores, by streams and in colourful gardens. The disruption of these magical scenes with images of barren and threatening landscapes echoes perfectly the celebration and torment of love explored in the sonnets.

Shot on Super-8 before being transferred to 35mm film, the unique technical approach results in a striking aesthetic, with Coil’s languorous soundtrack completing the intoxicating effect.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• James Bidgood

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally

• Un Chant d’Amour by Jean Genet

The life and work of Derek Jarman

The Angelic Conversation, 1985.

An unseen woman recites Shakespeare’s sonnets—fourteen in all—as a man wordlessly seeks his heart’s desire. The photography is stop-motion, the music is ethereal, the scenery is often elemental: boulders and smaller rocks, the sea, smoke or fog, and a garden. The man is on an odyssey following his love. But he must first, as the sonnet says, know what conscience is. So, before he can be united with his love, he must purify himself. He does so, bathing a tattooed figure (an angel, perhaps) and humbling himself in front of this being. He also prepares himself with water and through his journey and his meditations. Finally, he is united with his fair friend.