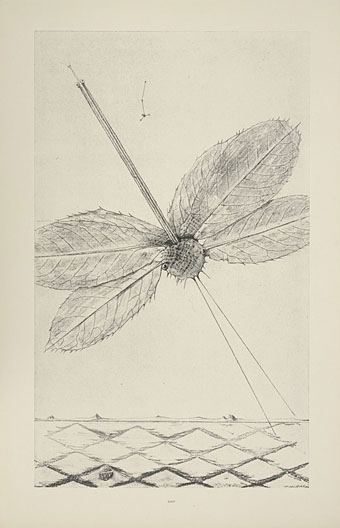

Teenage Lightning (Les Éclairs au-dessous de quatorze ans) (c. 1925) by Max Ernst.

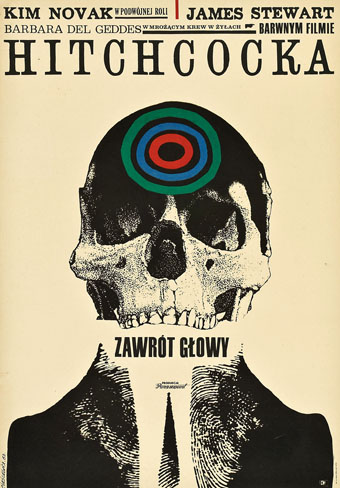

• “There has never been another director who has lain in wait for us with the same wrath or disgust. He is so complicated that finally he became the very thing he was nervous of admitting, a true artist best measured in the company of Patrick Hamilton, Francis Bacon, or Harold Pinter. He saw no reason to like us or himself.” David Thomson on why Alfred Hitchcock’s films still feel dangerous.

• New music: “Habitat, an environmental music collaboration by Berlin based composer Niklas Kramer and percussionist Joda Foerster, is inspired by the drawings of Italian architect Ettore Sottsass. Each of the eight tracks represents a room in an imaginary building.”

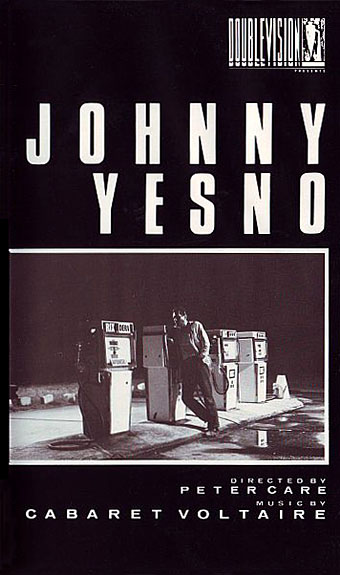

• “You could describe Lambkin’s work as a rich sort of ambient music, but largely without the synthetic textures that ambient music often possesses.” Geeta Dayal reviews Solos, a collection of recordings by Graham Lambkin.

• Tom of Finland: Pen and Ink, 1965–1989 is an exhibition at the David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, which runs to 1st May. The website includes a virtual tour.

• More revenant gay art: Bibliothèque Gay reviews a new Spanish translation of Baiser de Narcisse by Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen.

• Introducing Ark Surreal: “Surreal collages by Allan Randolph Kausch. Some cute and sweet, others dark and intriguing.”

• At Artforum: Albert Mobilio on Extra Ordinary: Magic, Mystery, and Imagination in American Realism.

• At Spoon & Tamago: Shizuoka is installing monuments inspired by their plastic model industry.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Jordan Belson Day.

• RIP Bertrand Tavernier.

• Teenage Lightning 2 (1991) by Coil | Teenage Lightning (1992) by Skullflower | Teenage Lightning (Surgeon Remix) (2001) by Coil