Imaginary (no date) by Sidney Sime.

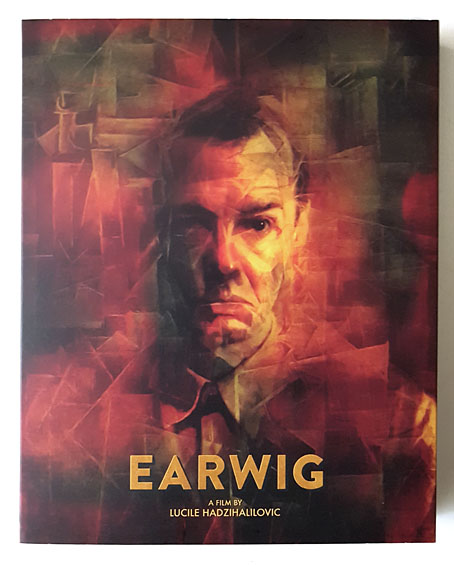

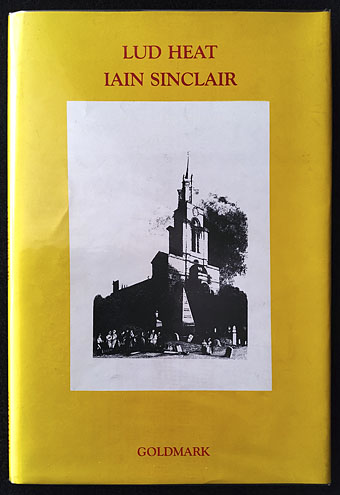

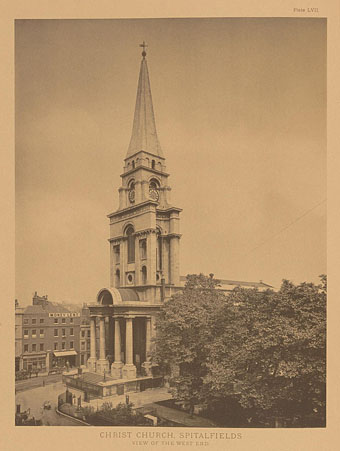

• Victor Rees was in touch this week to alert me to a one-off screening of The Gourmet (previously), a cult TV drama from 1986 written by Kazuo Ishiguro and directed by Michael Whyte. The screening, which will take place at Swedenborg House, London, on 16th October, is one of a series of retrospective events based around an exhibition from 1974, Albion Island Vortex, by Brian Catling and Iain Sinclair. The film, which is connected to Sinclair’s oeuvre by its use of one of the Hawksmoor churches, will be followed by a Q&A session with Sinclair and Michael Whyte. The screening is free but places are limited so prior booking is required.

• “Alongside his thieves and vagabonds, Hotten includes religious slang, public schoolboy slang, pirate slang, equine stable slang, phrases coined by Dr. Johnson, the slang of softened oaths, workmen’s slang, stagehand slang, shopkeeper’s slang, and dozens of other argots.” Hunter Dukes on A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words (1860) by John Camden Hotten.

• The Night Land, William Hope Hodgson’s “Dying Earth” doorstop, is republished in an abridged version as part of MIT Press’s Radium Age series, “proto–science fiction stories from the underappreciated era between 1900 and 1935”. All the reprints come with new introductions, the one for Hodgson being by Erik Davis.

• “My partner wanted me to stop buying lava lamps. It was an expensive hobby, and we were running out of room in our apartment.” Nora Claire Miller on the lure of the lava lamp. I only own a single one but I appreciate the obsessive attraction.

• Rambalac takes his roaming camera for a walk through teamLab Planets, Tokyo, a labyrinthine exhibition featuring plenty of water (and wet feet), and a moss garden filled with large silver eggs.

• At Strange Flowers: An examination of the connections between the self-mythologising Marie Corelli and her fictional counterparts in the Mapp and Lucia novels of EF Benson.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: Cabarets of Death, a book about the otherworldly cabarets of Montmartre by Mel Gordon, edited by Joanna Ebenstein.

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Secret Glory by Arthur Machen.

• 10 essential Japanese reggae releases selected by Kay Suzuki.

• Mix of the week: A Fact Mix by Venus Ex Machina.

• Modern Art in Mid-Century Comics.

• RIP Michael Gambon.

• Planet Caravan (1970) by Black Sabbath | Planet Queen (1971) by T. Rex | Oszillator Planet Concert (1971) by Tangerine Dream