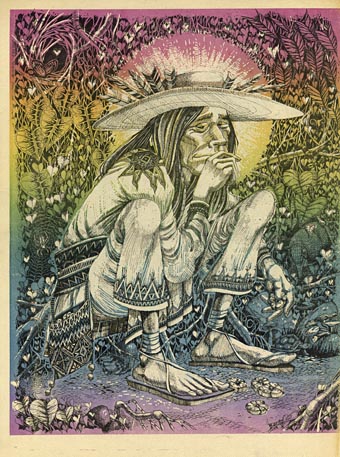

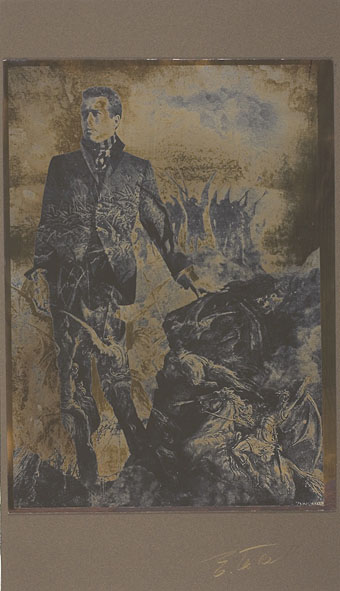

Kenneth Anger, Topanga Canyon (composite with Gustave Doré engraving) (1954) by Edmund Teske.

The other day…I had a date with Tom Luddy at a New York hotel in the East Fifties to meet Kenneth Anger, the genius who made Scorpio Rising and whose New York flat is a shrine to Valentino.

Michael Powell, from A Life in Movies, 1986

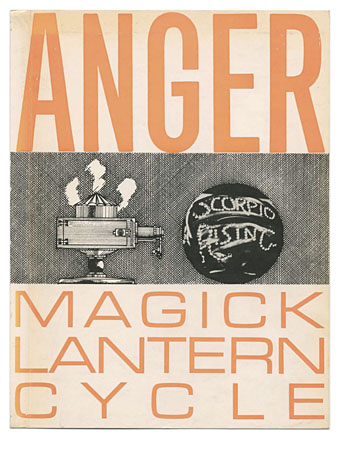

There’s not much I can add to all the plaudits, especially when Kenneth Anger has been a continual fixture here since 2007, with the last post about him going up only two weeks ago. I always find it impossible to make one of those lists where people name their ten favourite films but Anger’s Magick Lantern Cycle is one of the very few titles I could add to such a list, and it probably sits in the top five. What the other four might be depends on changes of mood or weather.

The most Anger recent post came about after I’d been re-reading the unofficial Bill Landis biography, a book I’d dipped into over the years but not gone all the way through again since it was published in 1995. It’s an uneven study of Anger’s life and erratic career, detailed yet slapdash, but Landis did at least interview many of Anger’s colleagues and acquaintances while they were still around. Even though Anger himself hated the results of the often gossipy investigation the book will remain an invaluable resource for future writers.

Some links:

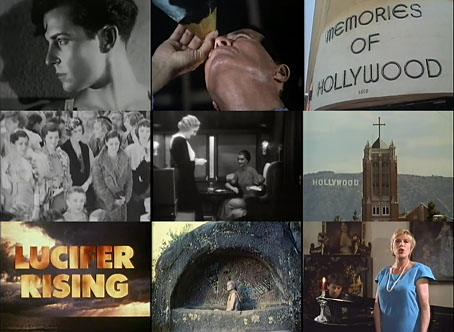

• Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon (1991). In which Nigel Finch persuaded a reluctant Anger to drive around Los Angeles in a hearse visiting sites of death or disaster mentioned in Anger’s first book. I suspect Finch was more interested in discussing Anger’s films, which are also featured, but needed the scandalous stuff to get the thing made at all. The BBC hadn’t done anything about Anger before this, and haven’t done anything since.

• Kenneth Anger–Magier des Untergrundfilms (1970), a 53-minute documentary made for WDR by Reinhold E. Thiel. A frustrating film, being a mix of awkward interviews (Anger didn’t like Herr Thiel very much) with priceless footage showing the filming of parts of Lucifer Rising. A shame, then, that all the copies which have been circulating for the past decade are low-grade and blighted throughout by one of those proprietary signatures that idiots stick onto footage they don’t own. WDR must still have the film so maybe we’ll get to see a better copy one day.

• Sex, Satanism, Manson, Murder, and LSD: Kenneth Anger tells his tale. Paul Gallagher recounts his own meetings with Anger and also posts several Anger-related pages from Kinokaze zine, 1993.

• Hollywood Bohemia: An interview with Kenneth Anger by AL Bardach for Wet magazine, 1980.

Previously on { feuilleton }

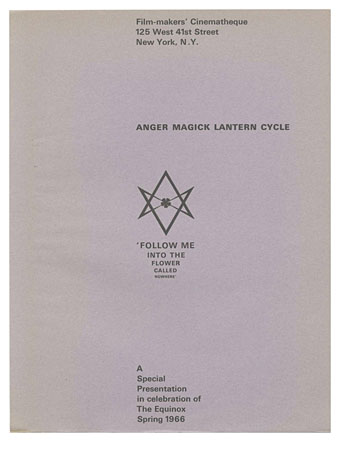

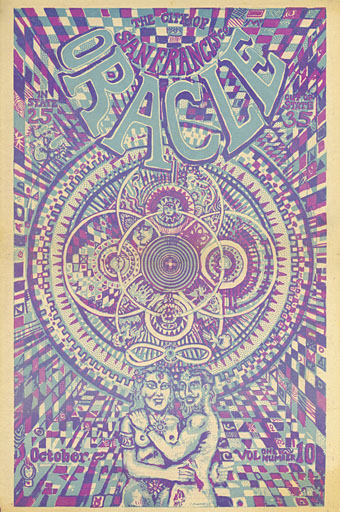

• Anger Magick Lantern Cycle, 1966

• Don’t Smoke That Cigarette by Kenneth Anger

• Kenneth Anger’s Maldoror

• Donald Cammell and Kenneth Anger, 1972

• My Surfing Lucifer by Kenneth Anger

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome: The Eldorado Edition

• Brush of Baphomet by Kenneth Anger

• Anger Sees Red

• Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon

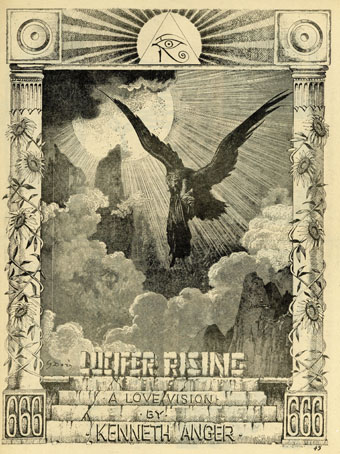

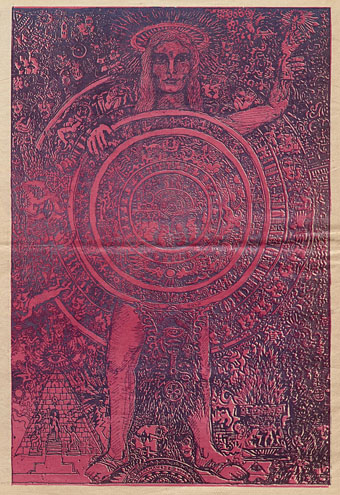

• Lucifer Rising posters

• Missoni by Kenneth Anger

• Anger in London

• Arabesque for Kenneth Anger by Marie Menken

• Edmund Teske

• Kenneth Anger on DVD again

• Mouse Heaven by Kenneth Anger

• The Man We Want to Hang by Kenneth Anger

• Relighting the Magick Lantern

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally