For the past week I’ve been reading the Strange Attractor Press edition of England’s Hidden Reverse by David Keenan, a book that’s not only a handsome volume in its own right but is also an excellent chronicle of the post-Throbbing Gristle Industrial scene in Britain from the late 70s to the present. There’s too much I could say about that side of the 1980s since it was a part of the decade I was fully immersed in. Not only the music either; I still have correspondence with some of the key figures (David Tibet among them), and accumulated a mass of newspaper and magazine features, reviews and interviews. The internet has rendered this aspect of the hoarding imperative redundant but pre-internet if you didn’t keep old papers and magazines then the information in them was effectively gone forever, especially if the publications were fanzines or small-run amateur mags that wouldn’t be archived by libraries.

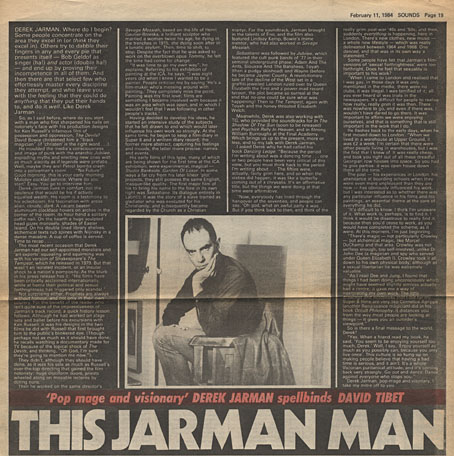

Keenan’s book prompted me to dig in some boxes to see what clippings had survived various relocations. Most of the stuff was familiar but I’d forgotten this piece from David Tibet’s fleeting career as a music journalist before Current 93 established themselves. Derek Jarman gets a passing mention in Keenan’s book via his connections with Throbbing Gristle and Coil, two groups who provided soundtracks for his films. Tibet’s interview was occasioned by the publication of Dancing Ledge, Jarman’s diary/memoir that’s been quoted here on several occasions. Tibet was writing for Sounds on this occasion, an unusual venue for a piece about Derek Jarman (Sounds was always more rock-oriented than the NME) which no doubt explains the lengthy contextualising; I’m sure Tibet would have preferred to talk more about John Dee and Jarman’s magickal preoccupations. Not a great interview, then, but a curious meeting that reinforces some of the connections of the period.

* * *

THIS JARMAN MAN by David Tibet (Sounds, February 11, 1984)

DEREK JARMAN. Where do I begin? Some people concentrate on the area they excel in (or think they excel in). Others try to dabble their fingers in any and every pie that presents itself—Bob Geldof as singer (ha!) and actor (double ha!)—and end up by proving their incompetence in all of them. And then there are that select few who effortlessly master every discipline they attempt, and who leave you with the feeling that they could do anything that they put their hands to, and do it well. Like Derek Jarman…

So, as I said before, where do you start with a man who first sharpened his nails on notoriety’s face with his production designs for Ken Russell’s infamous film of possession and oppression, The Devils? David Bowie christened him a “black magician” (if ‘christen’ is the right word…

He moulded the media’s consciousness and image of punk with the anarchic Jubilee, exploding myths and erecting new ones with as much alacrity as if legends were prefabs. Well, maybe they are! Petrol bombs crash into a policeman’s room… “No Future”. Good morning, this is your early morning

Molotov cocktail service. Where do you start? Easy. You go to interview him.

Derek Jarman lives in comfort, not the opulence that would be his if activity equalled wealth. His room is a testimony to his eclecticism, his fascination with areas alien, cloudy, dark. A vacant beaten aluminium clockface hovers on arches in the corner of the room, its hour hand a solitary coffin nail. On the hearth a huge sculpted head gates morosely, shades of Easter Island. On his double lined library shelves, alchemical texts rub spines with Nijinsky in a danse macabre. A cup of coffee is served. Time to recap…

The most recent occasion that Derek Jarman had our self-appointed moralists and ‘art-experts’ squealing and squirming was with his version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which he released in 1979. But that wasn’t an isolated incident, or an insular shock to a nation’s pomposity. As the blurb in his press release has it: “His films have been critically acclaimed internationally, while at home their political and sexual forthrightness has triggered only scandal.”

Not surprising either. Prophets are always without honour, and not only in their own country. For the benefit of the reader who isn’t quite sure of the impressiveness of Jarman’s track record, a quick history lesson follows. Although he had worked on stage sets and ballet before his excursions with Ken Russell, it was his designs in the two films he did with Russell that first brought him to the public’s blinkered eye. (Though perhaps not as much as it should have done; he recalls watching a documentary made for TV because of the topical shock of The Devils, and thinking, “Oh god, I’m sure they’re going to mention me now.”)

They didn’t, although they should have done, as it his sets as much as Russell’s over-the-top directing that gained the film notoriety: huge cruciform doors, priests wheeled along on movable lecterns by doting nuns.

Then he worked on the same director’s Savage Messiah, based on the life of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, a brilliant sculptor who married a woman twice his age, he dying in the trenches in 1915, she dying soon after in a lunatic asylum. Then, time to shift, to stop. Despite the fact that he was asked to work on the overblown opus Tommy, he felt the time had come for change.

“It was time to go my own way”, he explains. Referring to his exhibition of painting at the ICA, he says, “I was eight years old when I knew I wanted to be a painter. People criticise me by saying ‘He’s a film-maker who’s messing around with painting.’ They completely miss the point. Painting was my first love; films are something I became involved with because it was an area which was open, and in which I wouldn’t feel that I was following in other people’s tracks.”

Having decided to develop his ideas, he started an intensive study of the subjects that he felt drawn to and which would later, influence his own work so strongly. At the same time, he began to keep a film-diary in Super 8 and a written diary record; the former more abstract, capturing his feelings and moods, the latter more precise: names and events.

His early films of this type, many of which are being shown for the first time at the ICA exhibition, were experimental, magical—Studio Bankside, Garden Of Luxor. In some ways a far cry from his later linear ‘plot’ projects, they stiil possess the same English, masque-like quality. The first major film of his to bring his name to the fore in its own right was Sebastiane. Its dialogue entirely in Latin (!), it was the story of a slave trained as gladiator who was executed for his Christianity, and subsequently became regarded by the church as a Christian martyr. For the soundtrack, Jarman brought in the talents of Eno, and the film also featured Lindsay Kemp, Bowie’s mime mentor, who had also worked in Savage Messiah.

Sebastiane was followed by Jubilee, which featured the cult punk bands of ’77 in their seminal underground phase: Adam And The Ants, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Toyah (then a pudgy skinhead) and Wayne (before he became Jayne) County. A revolutionary tale of the decline of the West set in a graffiti-jewelled London ruled over by Queen Elizabeth the First and a power-mad record tycoon, the plot became so surreal at the end that no-one could be sure what was happening! Then to The Tempest, again with Toyah and the honey-throated Elisabeth Welch.

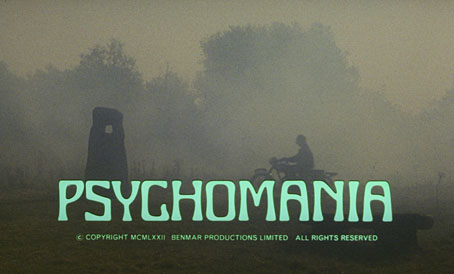

Meanwhile, Derek was also working with [Throbbing Gristle], who provided the soundtracks for In The Shadow Of The Sun (soon to be released) and Psychick Rally In Heaven, and in filming William Burroughs at the Final Academy. Which brings us up to the present, more or less, and to my talk with Derek Jarman.

I asked Derek why he had called his book Dancing Ledge. “Because the period I’m writing about was a dancing time…one or two people have been very critical of this view, but you must think back to the period I’m writing about… The fifties were, actually, fairly grim here, and so when the sixties did happen, it was like a butterfly coming out of a chrysalis. It’s an affirmative title, but the things we were doing at that time were affirmative.

“Now, everybody has lived through the hangover of the seventies, and people can say. ‘Oh god, what an awful party it was. But if you think back to then, and think of the really grim post-war ’40s and ’50s; and then, suddenly everything is happening, here in London. There’s new clothes, new music—a whole new lifestyle—which was really delineated between 1964 and 1968. One danced, and that was in its own way a statement.”

Some people have felt that Jarman’s fiIm versions of ‘sexual forthrightness’ were too forthright. Does he feel that sexuality is important to his work?

“When I came to London and realised that I was gay, in those days it was only mentioned in the media; there were no clubs, it was illegal. I was terrified of it; all you ever heard of was trials in the newspapers. It’s difficult for people to realise how really, really grim it was then. There was nowhere to go, and even if there was, I wouldn’t have dared to go there. It was important to affirm we were enjoying ourselves, and that is something that is still important in the work that I do.

He flashes back to the early days, when he first moved down to London: “When we lived in a warehouse at Upper Ground, it was £2 a week. I’m certain that there were other people living in warehouses, but I was the first that I knew of. It was really cheap, and took you right out of all these dreadful Georgian row houses into space. So you had to give parties: it was open house down there all the time.”

The past—his experiences in London, his attendance at boarding schools when they were even more unpleasant than they are now—has obviously influenced his work, but I was interested as to whether there was any particular influence in his films and his paintings, an essential theme at the core of everything he did.

“It’s difficult to know. I think I’m unaware of it. What work is, perhaps, is to find it. I think it would be disastrous to really find it, because then you’d cease to work, as you would have completed the scheme, as it were. At this moment, I’m just beginning.

“There’s magic—not particularly Crowley—but alchemical magic, like Marcel Duchamp and that area. Crowley was not selfless enough, too self-involved, unlike Dr John Dee (a magician and spy who served under Queen Elizabeth I). Crowley took it all down to his own physical body, although as a sexual libertarian he was extremely valuable.

“As I read Dee and Jung, I found that things I had been doing unconsciously which might have seemed slightly aimless actually had a centre; it gave me a way of interpreting my own work. The little drawings and notebooks that I did for my Super 8 films are very like Cornelius Agrippa (another Renaissance magician) did in his book Occult Philosophy. It distances you from the way most people are looking at things—it gives you an outsiders viewpoint.”

So is there a final message to the world, Derek?

“Yes. When a friend read my book he said, ‘You seem to be enjoying yourself too much, Derek. Well, I say, ‘Enjoy yourself as much as you possibly can. because you only live once’. This culture is so hung up on making people believe that having a bad time is serious, and it ain’t. It’s a whole Victorian puritanical attitude, and it’s coming back very strongly. Go out and dance. Dance against everyone who stops you.”

Derek Jarman pop-mage and visionary, I take my mitre off to you. •

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Shooting the Hunter: a tribute to Derek Jarman

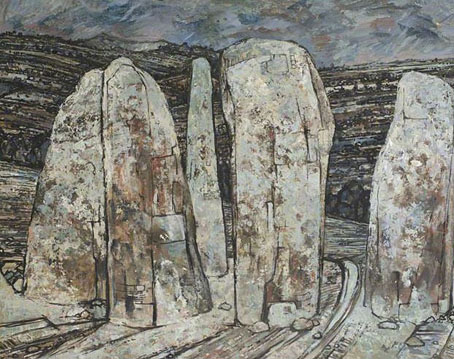

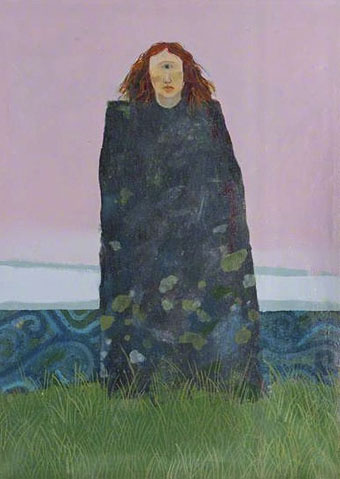

• Derek Jarman’s landscapes

• Derek Jarman album covers

• Ostia, a film by Julian Cole

• Derek Jarman In The Key Of Blue

• The Dream Machine

• Jarman (all this maddening beauty)

• Sebastiane by Derek Jarman

• A Journey to Avebury by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman’s music videos

• Derek Jarman’s Neutron

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• The Tempest illustrated

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman