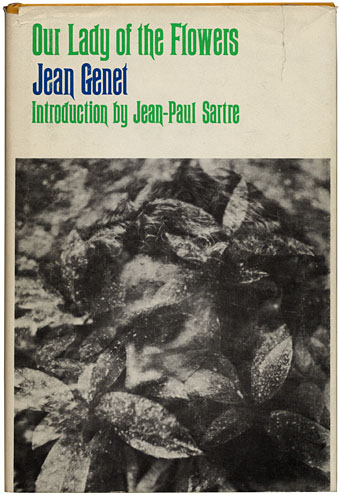

Untitled (1963).

One of a small number of pictures from a recent exhibition of work by American photographer Emil Cadoo (1926–2002) whose nude studies and often homoerotic themes were controversial in America of the Fifties and Sixties but welcomed in France, as was often the case at that time.

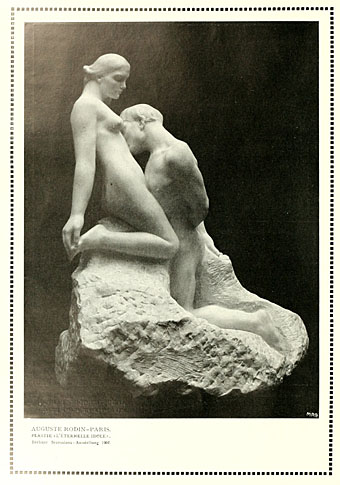

In April 1964, all 21,000 copies of the April/May issue no.32 of the American magazine Evergreen Review – containing (among others) texts by Norman Mailer, Jean Genet, William Burroughs, Bryon Gysin, Michael McClure, Karl Shapiro (a who’s who of the day’s practitioners of perceived outrage), and an erotic photo-essay by Cadoo – was seized by the police whilst it was still being bound. The edition had been deemed ‘obscene’ by the county’s district Attorney, whose particular disapproval was leveled at Cadoo. It took the special intermission of Edward Steichen, who compared the images to the work of Auguste Rodin “the greatest living sculptor of our time”, to obtain the condemnation of three judges of this action as ‘unconstitutional’, and to return the magazine to the public domain. (More.)

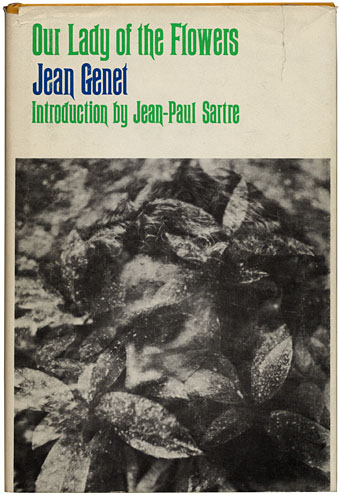

Cadoo favoured the double-exposure to achieve painterly or (for want of a better word) “poetic” effects, and some of these photos were used on book jackets by Grove Press (also the publishers of Evergreen Review), among them this Genet title which I posted a couple of years ago. More of Cadoo’s work can be found on various gallery sites but there’s no dedicated site unfortunately.

Photo by Emil Cadoo; design by Roy Kuhlman (1963).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Penguin Labyrinths and the Thief’s Journal

• Un Chant d’Amour by Jean Genet