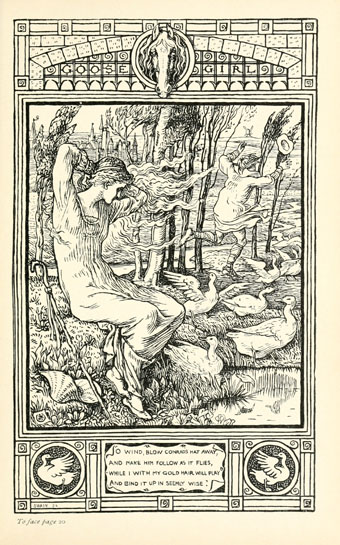

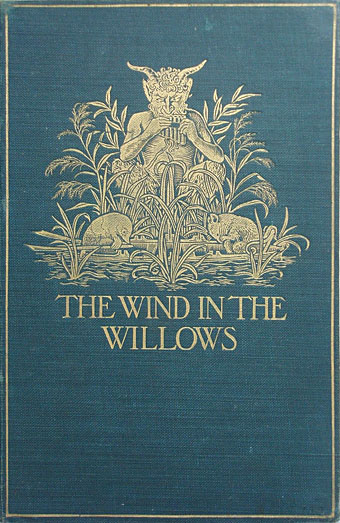

Illustration by W. Graham Robertson (19o8).

(No, this doesn’t concern Pink Floyd.)

The chapter – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – is normally dropped because it jars, seems so strange compared to all the others and, to some, is vaguely homoerotic. [Kenneth] Grahame thought it essential.

Thus Mark Brown discussing the curious seventh chapter of The Wind in the Willows (1908) wherein Mole and Rat have a mystical encounter with the Greek god of nature in the British countryside:

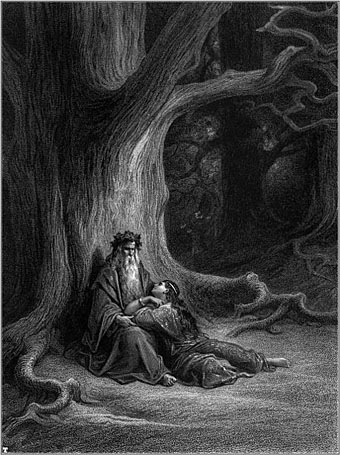

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

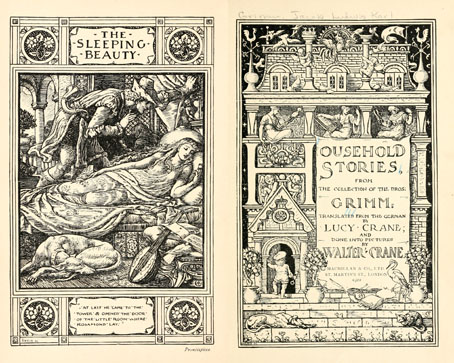

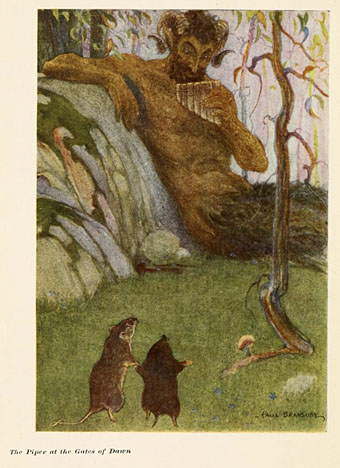

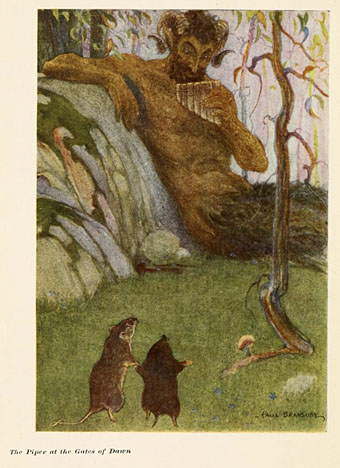

Brown’s article concerns a forthcoming exhibition, Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands, at the British Library, part of the summer’s Olympic celebrations. Kenneth Grahame’s hand-written text of chapter seven will be on display together with a later Arthur Rackham illustration of the goat god. The Library makes a point of noting that the Pan chapter is sometimes excised from the book although I’m not sure how often this occurs, it’s been present in all the editions I’ve seen including the cheap paperback edition I have somewhere. W. Graham Robertson’s rather fine drawing above (showing Mole and Rat bowing to their presiding deity) embellishes the first UK edition. Paul Bransom’s illustration below is the frontispiece to a 1913 US edition.

Illustration by Paul Bransom (1913).

One benefit of this bit of news has been finding Robertson’s illustration which gives Brown’s use of “homoerotic” a slight twist. Robertson was a children’s illustrator and playwright who Neil McKenna in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2003) describes as being a member of the surreptitiously gay art world in London during the 1890s. (If there’s to be any dissent about this let’s note that one of his plays was entitled Pinkie and the Fairies…) Robertson knew Oscar Wilde but fell in with the contra-Wilde fraternity, notably Robert de Montesquiou, so gets left out of many accounts of Wilde’s circle. He was however immortalised by John Singer Sargent in this well-known portrait. I’ll be writing a little more about Robertson and Sargent’s painting at a later date. For more about the surprising recurrence of Pan in Victorian and Edwardian literature, see this earlier post.

Writing Britain: Wastelands to Wonderlands at the British Library opens on May 11th and runs throughout the summer.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrator’s archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Great God Pan

• Peake’s Pan