Ulysses is a book to own, a book to live with. To borrow it is probably worse than useless, for the sense of urgency imposed by a time-limit for reading it fights against the book’s slow pace, a leisurely music that requires an unhurried ear and yields little to the cursory, newspaper-nurtured eye. Most of our reading is, in fact, eye-reading—the swallowing whole of the cliché, the skipping of what seems insignificant, the tearing out of the sense from the form. Ulysses is, like Paradise Lost, an auditory work, and the sounds carry the sense. Similarly, the form carries the content, and if we try to ignore the word-play, the parodies and pastiches, in order to find out what happens next, we are dooming ourselves to disappointment.

Thus spake Anthony Burgess in 1965. This year as Bloomsday rolls around again I find myself actually reading Ulysses on the day itself. I decided recently that enough time had elapsed since my last Joycean excursion and this time did something else I’d not tried before, reading Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses in sequence. The story of Leopold Bloom’s walk around the city was originally intended as a shorter piece for the Dubliners collection and many characters from Dubliners and Portrait turn up again in the later novel.

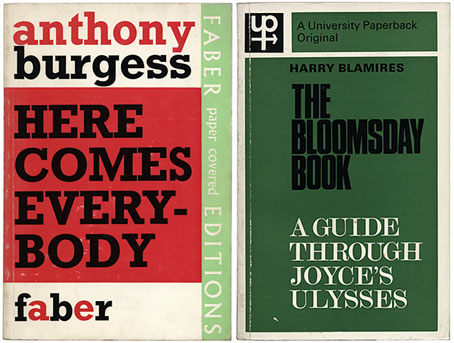

I first encountered Ulysses when I was about 17 and despite having read a fair amount of experimental or challenging fiction by that time still found it difficult and frequently nonsensical. A lack of context was the problem; one of the failings of the book—if we have to look for failings—is that it really does help to know something about Joyce’s intentions which otherwise remain opaque to an uninformed reader. So my first proper reading of the novel was helped considerably by the discovery in a library of Harry Blamires’ Bloomsday Book (1966) which goes through the entire novel virtually page by page, examining the symbolism and correspondences layered into the text.

Joyce’s alter-ego in Portrait and Ulysses was Stephen Dedalus, named after the mythological Daedalus who built the labyrinth for the minotaur. Anthony Burgess in Here Comes Everybody: An introduction to James Joyce for the ordinary reader (1965) describes Ulysses as Joyce’s labyrinth and both the Blamires and Burgess books are excellent guides to its literary maze. Blamires examines the minutiae (and occasionally overdoes the reading of religious symbolism) while Burgess takes a superb tour through the entire corpus, often bringing to Ulysses a quality of understanding which Blamires lacks. Here Comes Everybody is an ideal introduction for those curious about Joyce’s work and reputation but who feel intimidated when they pick up the books. It’s a shame that Burgess’s title—a phrase of Joyce’s lifted from Finnegans Wake—has been hijacked recently by a book about internet culture. Burgess’s book also appears to be out of print so anyone looking for a copy is advised to try Abebooks.com. Blamires’ book is still in print in a revised edition and for another notable writer’s view there’s Nabokov’s lucid exposition in his Lectures on Literature. And if all that doesn’t satisfy, there’s always The Brazen Head.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Finnegan begin again

• T&H: At the Sign of the Dolphin