Semina, #1–9.

A Return Trip to a Faraway Place Called Underground

By HOLLAND COTTER

New York Times, January 26, 2007

Time is forever. Love is the goal. Art is what you are, not what you do. Many young artists and poets in California in the 1950s and ’60s felt and lived this way. And a traveling band of them, trailing a cloud of marijuana-fragrant air, has arrived at the Grey Art Gallery in “Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle.”

The mostly dense paintings, drawings and collages in the show make visual sense in New York today. Updated versions of their type have flooded galleries in the last few years. Yet the throwaway, amateur-proud spirit that propelled the older work is largely absent in the new. It belongs to another time and place, with a different set of possibilities and necessities, to a small imploded star, now far, far away, called Underground.

The artist Wallace Berman (1926-76) lived on that star. His name still rings only a faint bell. Actually, he was something of a mystery even to his friends, who were legion and seem to have loved him deeply. And as the show, a kind of scrapbook of art and ephemera, makes clear, three decades after his death he is well worth getting to know.

Born in Staten Island, a child of Russian Jews, he moved to Los Angeles with his family when he was 9 and turned into a classic California oddball. He loved sports, jazz, mind-altering substances, Dada, inside jokes and esoteric spiritual systems, notably the kabbalah. A spiritually minded secularist, he was intensely sociable and intensely quiet, a family man whose house was open to all.

He was also a collagist, painter, photographer and poet; his immersion in art was complete. He not only made it but also inspired others to make it, sparking hidden aptitude in startling places. After meeting him, drifters, movie stars, ex-marines and petty criminals found themselves starting to paint and write.

By temperament a collaborator, he was also, in his nonentrepreneurial way, a promoter. With other artists, he briefly opened a gallery in a roofless houseboat and gave one-day shows to people he admired. Shy of showing his own work, he had few exhibitions; one, at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1957, was particularly memorable. It led to his arrest for exhibiting lewd material.

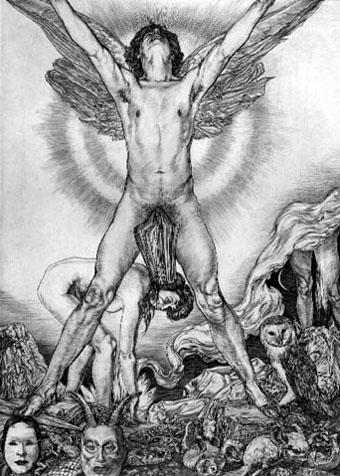

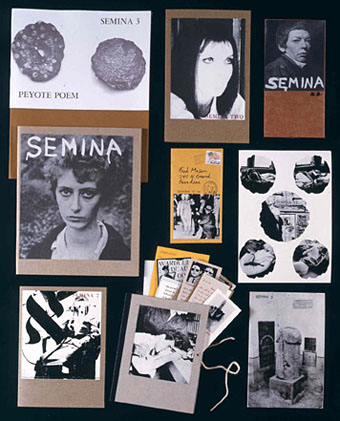

The offending piece, a drawing of a copulating couple, was not by him but by a friend, Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (1922-95), an artist, performer and occult practitioner who went by the single name Cameron. (She is currently the subject of a solo show at Nicole Klagsbrun in Chelsea.) The image appeared in the first issue of Mr. Berman’s loose-leaf journal, Semina, copies of which he had scattered around the gallery floor.

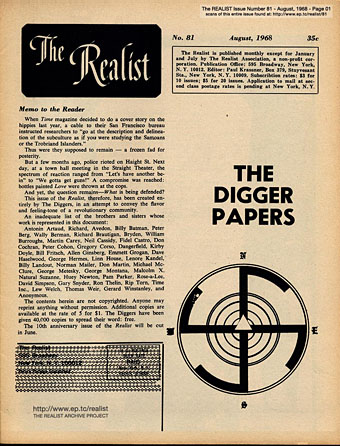

It was Semina that carried Mr. Berman, and the artists and poets he championed, beyond a local audience. He produced the journal from 1955 to 1964 on a mail-order hand press with the help of two friends, the artist and poet Robert Alexander and the photographer Charles Brittin. There were only nine issues. The print run was minute. The contents were mind-boggling.

The magazine, its pages randomly compiled, mixed Berman heroes like Antonin Artaud and Jean Cocteau with established American poets like Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg, then added a slew of younger writers and artists — Philip Lamantia, Jack Anderson, Patricia Jordan, Kirby Doyle, Bob Kaufman, Aya Tarlow, Ruth Weiss, Michael McClure, the great gay poet John Wieners — all barely out of the starting gate. Sent, copy by copy, through the mail, Semina defined a distinctively trippy, sardonic West Coast surrealism. New York had hard, cold Pop; the West Coast had a woozy Peyote-Funk that prefigured the hippie era.

If the journal put Wallace Berman’s name on the national countercultural grapevine, his personal influence was still transmitted through artists and poets who met him. And four dozen of them take brief, individual bows in a show — organized for the Santa Monica Museum of Art by two independent curators and critics, Michael Duncan and Kristine McKenna — that feels like both a slice of still-warm history and a reliquary.

Several of the artists are now far better known than Mr. Berman himself. Joan Brown (1938-90), Bruce Conner and Jay De Feo (1929-89) are textbook figures. Ms. Brown’s fetishistic “Man on Horseback,” a 1957 sculpture of rolled and tied cloth, is an eye-catcher. So are two sumptuously abject assemblages by Mr. Conner, who also has an outstanding show of early work at Susan Inglett Gallery in Chelsea.

And for relics, there’s the pigment-caked footstool that Ms. De Feo used while creating “The Rose,” a painting that grew so heavy with applied matter that, at 2,000 pounds, it had to be forklifted from her tenement studio.

More famous at the time were Hollywood actors like Dean Stockwell and Russ Tamblyn, who met Mr. Berman and started making art. Another was Dennis Hopper, who picked up photography and film directing. (He cast Mr. Berman in a small role in “Easy Rider.”) And there was Billy Gray. A teenage heartthrob as Bud Anderson on “Father Knows Best,” he started making stained-glass sculptures after a drug arrest in 1962 crippled his show business career.

Chemicals of all descriptions gradually pulled the Berman circle down. It comes as a dawning shock to walk through the show and see so many young faces accompanied by so many curtailed dates.

The Pop assemblagist Ben Talbert and the abstract painter Arthur Richer died of drug overdoses in their early 40s. The Hollywood child actor Bobby Driscoll, the voice of Peter Pan in the Disney film and the creator of four glorious little collages in the show, was taken out by heroin at 31. By the end of the 1960s, methamphetamines had ruined John Reed, another wonderful artist and poet; he died homeless, almost all his work lost.

Three of these four, Richer being the exception, had little if any formal art training. They could be called outsider artists, except — well, except what? They weren’t crazy enough, or poor enough, or “ethnic” enough, or in some other way picturesque enough to qualify for that exaltedly abject name?

Their work is interesting in large part exactly because it muddies market-driven aesthetic divisions instituted since their day: artist versus outsider artist, trained versus self-taught, professional versus amateur. Most of the artists in the show fall on the alternative side of the equations.

In fact, one of the things that made them a “circle,” if they can really be called that, was their shared lack of traditional bona fides. They were artists because they said they were, and acted as if they were, and because someone — Wallace Berman — said, “You are.” Where would they have stood in relation to today’s standardized, professionalized art industry? Where do such artists stand today, since there are surely many out there, living artists’ lives?

Anyway, for the purposes of the exhibition, the Berman connection is the crucial link, the bond that makes outsiders insiders. They are held within his orbit, which Mr. Duncan and Ms. McKenna, in their charismatic catalog, depict as an accepting, protective space.

Acceptance, and the psychological protection it affords, are rare and invaluable. Are they extended to artists today, to all artists, equally? They should be. They must have felt especially necessary as the cold war 1950s turned into the Vietnam War 1960s, as modern art moved into its radically disruptive postmodern phase.

And as casualties among the artists and poets gathered in the show began to grow, no high in the world could have hidden the truth that time is very short, and that love is only as trustworthy as its object. People trusted Mr. Berman; that was the bottom line. They found him steady and there. I don’t believe in gurus, and especially not in art gurus, even those like Wallace Berman who didn’t want to be one. But I can understand why, when he died after being hit by a drunken driver on the eve of his 50th birthday, there was much grief.

“Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle” continues through March 31 at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 100 Washington Square East, Greenwich Village, (212) 998-6780, nyu.edu/greyart.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Cameron, 1922–1955