Long, Strange Trip for a Hypnotic Film

Long, Strange Trip for a Hypnotic Film

By James Gaddy

August 27, 2006

The New York Times

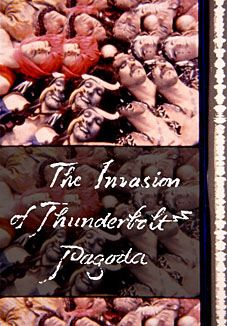

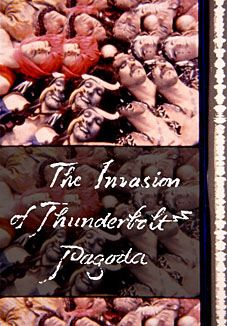

IT TOOK 38 years, but Ira Cohen’s cult film, The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda, which was first screened in 1968 at the high point of the psychedelic hippie head rush, is now commercially available. Given the close calls, the long absences and his chaotic archival system, Mr. Cohen, 71, is a little surprised himself.

“It didn’t really involve patience,” he said in his apartment on West 106th Street in Manhattan, surrounded by books stacked waist high. “It was just reality.”

In 1961 Mr. Cohen built a room in his New York loft lined with large panels of Mylar plastic, a sort of bendable mirror that causes images to crackle and swirl in hypnotic, sometimes beautiful patterns. After a few years experimenting with the technique in photographs, he invited his friends from the downtown scene—like Beverly Grant, Vali Myers and Tony Conrad—to make a film.

The finished product sets languid images of opium smokers (in fantastic makeup and costumes) against a droning, chanting, tabla-beating soundtrack by Angus MacLise, the original drummer of the Velvet Underground. Xavier Garcia Bardon, film curator at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, said the film is an important artifact of the era.

“It’s like going on an ecstatic journey to another planet, full of magical beings, animals and plants,” he said. “It’s a hallucinatory, almost trance-inducing experience.”

Mr. Cohen left New York in 1969, shortly after the film’s first screening, for art- and drug-filled travels in India, Ethiopia and Nepal. He roamed through the 1970s and 80s. While he was away, the film’s legend grew, even as the original few copies slowly disappeared.

Mr. Cohen said he dropped off the original print at DuArt Film Laboratories before he left; the staff reached him in Kathmandu in 1978, asking for $300 in storage fees. He asked the lab to send the print to the Museum of Modern Art, but the museum has no record of receiving it.

“If you have money, you can store it any way you want,” he said ruefully. “But for some people, $280, $300 changes the way things turn out.”

It wasn’t until a compilation of Mr. MacLise’s music came out in 1999, 20 years after his death, that interest in distributing the film began. Jay Babcock, editor of the underground magazine Arthur, and Will Swofford, a composer who was then studying at Wesleyan University, independently tracked Mr. Cohen down.

Mr. Babcock said he was curious to see how Mr. Cohen’s early Mylar photographs would look like in a film. “I had dreamed for years what it would look like,” Mr. Babcock said. He began pressing for distribution rights.

Meanwhile Mr. Swofford had persuaded Mr. Cohen, whose health has been failing (he’s had two strokes in the last year), to let him operate as an archivist and agent. Mr. Swofford eventually found 40 cans of unused outtakes in a green trunk, buried beneath books, papers, slides and assorted creative runoff.

“No one had touched the film for 25 years,” Mr. Swofford said.

Because the original version lasts only 22 minutes, he began beefing>up the content for the DVD age. Mr. Cohen wanted to use part of the found film, an eight-minute section in which he is buried in mud, as a prelude; Mr. Swofford used the nearly four hours of outtakes to fashion Brain Damage, a 30-minute coda. The DVD also features a slide show of Mr. Cohen’s photographs, audio recitations of his poetry and two alternate soundtracks to the film.

One of these versions was by the band Acid Mothers Temple, which had recorded a live soundtrack to the film at the music festival Kill Your Timid Notion, in Dundee, Scotland, in 2003.

“I had no idea what a DVD could be,” Mr. Cohen said. “I would have just put the film on there.”

The film was released last month, the result of a collaboration between Bastet, Arthur magazine’s music and video label, and Saturnalia, Mr. Swofford’s label, with distribution limited to the magazine’s Web site and a few independent music retailers. Thanks to labor donated by both parties, the initial 1,000-copy print run cost about $8,000.

But $8,000 is still a lot of money for a magazine like Arthur, a break-even labor-of-love venture. “It’s shameful, with the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on movies every year in Hollywood, it’s left to a penniless publication to put this out,” Mr. Babcock said.

Yet he remains optimistic. The film received positive reviews when screened at the 2006 Whitney Biennial. Next month Mr. Bardon will hold a screening with live music in Brussels, and Tony Conrad, now a professor in the department of media studies at the University of Buffalo, will screen the film in Atlanta.

Mr. Babcock is already making plans to release Mr. Cohen’s two other films if Arthur can recoup the investment on this one. “We hope this is just the beginning,” he says.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda