Well they would, wouldn’t they?

More great absinthe posters here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Monsieur Chat

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Well they would, wouldn’t they?

More great absinthe posters here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Monsieur Chat

Monument to an Unknown Soldier: Portrait of an American Patriot (detail) by Michael Petry.

American artist Michael Petry has made works in the past using freshwater pearls threaded on sheets of black velvet. Viewers can admire the pearls then be disconcerted when given the additional information that the shapes they make are derived from those produced by human seminal emissions. A new work by Petry uses the same effect with a full-size US flag taking the place of the black velvet. The emission pattern in this case was produced by a gay American soldier and serves as a comment on the US military’s ridiculous “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy towards gay servicemen and women. The soldier in this instance must remain unknown or risk expulsion from the army.

It remains to be seen what reaction this will provoke when the work goes on display at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery in New York as part of the America the Beautiful exhibition. The flag in the United States is a sacred object in a way it could never be here and many patriots won’t take kindly to seeing it “besmirched” even if it is by a small arrangement of pearls. In this kind of work context is all. If people were told the pearls were arranged in the shape of the Marshall Islands (where the US conducted its nuclear tests) they’d be less upset than when informed as to the real origin of the design. Yet nothing would physically change; the flag and pearls would remain the same, all that would alter would be a single piece of information and the perception of the viewer.

White Flag (1955) by Jasper Johns.

Petry isn’t the first artist to use the American flag as a subject, of course, Jasper Johns (another gay artist, incidentally) produced a number of flag-derived paintings in the 1950s and 60s. His famous White Flag of 1955 was intended to be abstract rather than political (although it’s debatable how using such a highly-charged symbol could ever be unpolitical) but it’s interesting to consider how this would be viewed if it had been painted today. White flags are only used to signify surrender; in time of war Johns’ exercise in abstraction gains a new resonance.

Sundaram Tagore Gallery

547 West 27th Street,

New York.

Via Towleroad.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Army Day

Who or what is the mysterious, grinning yellow cat? Wikipedia explains:

M. Chat (also known as Monsieur Chat and Mr Chat) is the name of a graffiti cat that appeared in Paris and other European cities in the months and years following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The graffiti appeared most frequently on chimneys, but has been sighted in other places such as train platforms as well. It has also made appearances at political rallies. The originator of the street art remains anonymous.

The yellow cartoon cat is characterized by its large Cheshire Cat grin. The cat is most often portrayed in a running pose, but has also been variously depicted waving signal flags, bouncing on a ball, sporting angel wings, and waving in greeting at the entrance to a train station. It is sometimes accompanied by the tagline M. CHAT in small letters.

A shame I didn’t discover this phenomenon before I went to Paris last year, the city is cluttered with reproductions of Théophile Steinlen’s Chat Noir poster so it would have been fun to look for a more subversive animal. I found the wary creature below near the gardening market on the Ile de la Cité.

French filmmaker Chris Marker is famously a feline aficionado so it’s no surprise that he’s made a documentary entitled The Case of the Grinning Cat (Chats perchés) examining the appearance of M Chat through the twin lenses of his video camera and his political concerns. A French site, Monsieur Chat (et autres…), similarly documents occurrences of the mysterious animal and this is their page about Marker’s film. Finally, there’s a Flickr pool although with fewer photographs than one might hope.

Via City of Sound.

Update: Monsieur Chat’s creator revealed (in French).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Sans Soleil

First Robert Anton Wilson, now Alice Coltrane, widow of John Coltrane and one of my very favourite musicians. She died on Friday but it seems the news is only now circulating. A great musician (harp and keyboards) and a great composer, she managed to carve her own creative space away from the giant shadow of her husband. Even so, many of her early albums have yet to be reissued on CD outside Japan, a criminal state of affairs which tells you a lot about the way the music industry marginalises jazz and avant garde music. If you’ve never heard any of these recordings the best introduction is probably the Astral Meditations compilation but all the early works are flawless and essential.

A Monastic Trio (1967–68)

John Coltrane: Cosmic Music (1968)

Huntington Ashram Monastery (1969)

Ptah, the El Daoud (1970)

Journey in Satchidananda (1970)

Universal Consciousness (1972)

World Galaxy (1972)

Lord of Lords (1972)

John Coltrane: Infinity (1973)

Reflection on Creation and Space (A Five Year View) (1973)

The Elements (1973; with Joe Henderson)

Illuminations (1974; with Carlos Santana)

Radha-Krisna Nama Sankirtana (1976)

Transcendence (1977)

Transfiguration (1978)

Divine Songs (1987)

Translinear Light (2004; with Ravi Coltrane)

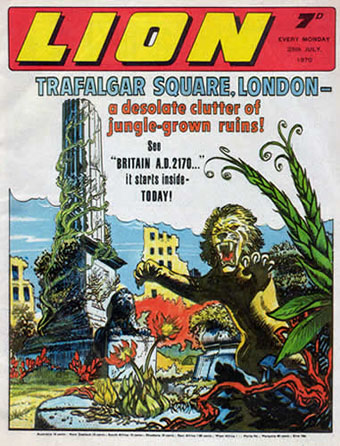

Ballard-for-kids from Lion (1970).

I was never a great hoarder of comics when I was a child, I usually read them then threw them away, so for years I’ve had peculiar half-memories of stories that thrilled me when I was 10-years old but whose titles I’ve invariably forgotten. The web, of course, serves to immediately answer desperately nagging questions such as “Who was the boy in a home-made catsuit climbing all over buildings at night?” (Billy the Cat, and sister Katie), “Which comic did bendable hero Janus Stark appear in?” (Smash and later Valiant), and so on.

British comics nearly always seemed stranger than American ones even though I was a regular reader of Spider-Man and a couple of other Marvel comics. Many of the British adventure titles—all long since expired—were created by artists and writers who drew freely on pulp traditions from the late 19th and early 20th century. Reading through histories of comics such as Lion it’s notable how many of the stories are set in the Victorian era. These tales were invariably hokey and certainly don’t bear much examination now but I can trace later interests back to an early stimulation by these odd strips.

The evil Ezra Creech.

I’m actually surprised to discover that I was a regular reader of Lion, its list of characters is very familiar yet I don’t remember buying a single issue. Lion is significant for being home to one of my favourite strips of the period, the chilling horror/thriller The War of the White Eyes. I’ve yet to meet anyone who remembers reading this which used to be frustrating when I’d pester comic-collecting friends to try and recall which title it appeared in. The story was fairly standard adventure fare from 1972:

The War Of The White Eyes was a US-type fantasy strip which had our heroes, Nick Dexter and Don Redding, trying to thwart the evil megalomaniac, Ezra Creech, who was baying for world domination by inhaling a deadly gas that transformed him into a ‘White-Eyes’, a creature of superhuman strength and ferocity. At first, Creech wanted to destroy our heroes’ home island of Doomcrag and then go on to world domination, but guess who stopped him?

If you live in a place called Doomcrag you’re asking for trouble. I didn’t remember there being a super-villain involved although someone had to be responsible for raining the globes of deadly gas down on the populace.

Creech could turn people into white-eyed zombies under his control. He had superhuman strength as a White Eye. He later developed a ray that allowed him to make things grow, giving him the ability to create monsters.

JMB Chemicals developed a new gas as a mild insecticide. However it proved to have unforeseen side-effects. Men and animals exposed to it were transformed into killers of extraordinary strength and ferocity, recognisable by their white eyes. The first evidence of this came when a few glasses containers of the gas accidentally dropped from the back of a van transporting them through the peaceful English town of Wimbering. Those exposed demonstrated an innate hatred of anyone untainted, and set out to conquer the area and kill “the weaklings”. Even the army proved helpless, with White Eyes ripping apart tanks with their bare hands and throwing them around like toys. Even the White Eyes animals joined in, with contaminated birds attacking troops on the ground. It was only through the bravery and ingenuity of local boys Nick Dexter and Don Redding, and the scientist Timms who had developed the gas in the first place (and also concocted an antidote) that order was restored.

This was very much a horror strip for kids—at least as I remember it—with crazed, white-eyed people and animals going on the rampage, and the ever-present danger that our heroes could be infected themselves. The strip taught me very early on that the simplest way to make someone look evil was to blank out their pupils, something I spent the rest of the decade doing in drawing after drawing.

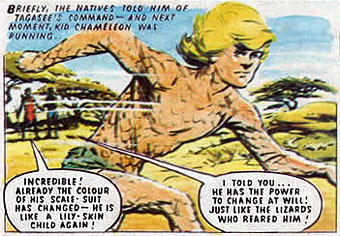

Kid Chameleon takes off.

Another favourite was Kid Chameleon (not to be confused with a later computer game character) whose adventures appeared in my favourite comic of the time, Cor!!:

Stranded in the Kalahari Desert by a plane crash, a British boy is raised by lizards as a feral child, and weaves himself a skin-tight suit of transparent lizard scales which covers his entire body except the top of his head (to avoid the appearance of complete nudity, he also wears a pair of flesh-coloured briefs underneath). Only one strip shows how the suit comes off. It consists of two pieces: a top that opens at the front, and leggings. The suit allows him to camouflage himself like a chameleon by making the scales change colour, although how he does it is never explained.

Yes, I was eagerly reading about a near-naked boy when I was 10; make of that what you will. Kid Chameleon spent two years tracking down the man who caused the plane crash before returning to the desert and the company of the lizards. This strikes me as a very Burroughs-esque idea now, there being plenty of lizard boys and skin suits in Burroughs’ early novels such as The Soft Machine and The Ticket that Exploded. In many ways, Kid Chameleon isn’t far removed from the various incarnations of the Wild Boys—resourceful, shape-shifting and always a loner. By a curious coincidence Burroughs was in London writing Port of Saints, the sequel to The Wild Boys, at the time Cor!! was publishing Kid Chameleon.

There aren’t any pages online from The War of the White Eyes; perhaps that’s for the best, it would only shatter my vague memories even further. However, you can see a couple of pages from Kid Chameleon here, written by Scott Goodall. The strip was drawn by Joe Colquhoun, later the artist on Charlie’s War by Pat Mills.