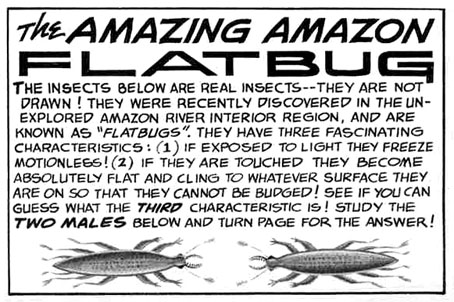

This one is for my own benefit as much as anyone else’s. Last week, after reading about the late Al Jaffee, I went looking for the panel you see above, a minor item in a much longer Jaffee feature for an issue of Mad magazine from the 1960s. The flatbugs have been one of my favourite Jaffee jokes for many years, but never having kept a note of which issue they appeared in I’ve always had a problem finding them when I’ve wanted to tell someone about them or see them again. On this occasion searches for various combinations of “mad”, “magazine”, “jaffee”, “bugs”, “flatbugs”, “flat bugs” yielded nothing other than a brief mention on a Reddit thread, along with too many articles about insect infestation. Google Books is sometimes useful for search leads but not this time. Twitter still has its uses, however; someone there had mentioned the flatbugs a couple of years ago, as well as the issue they appeared in, Mad no. 107 for December 1966, so here they are at last.

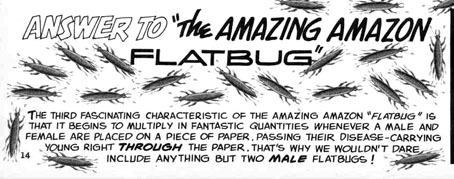

The thing that made the flatbugs so memorable (if not locatable) was that this is a rare Mad joke that’s allowed to extend throughout the rest of the issue. Jaffee’s bug panels occupied two corners of a three-page collection of puzzles and visual gags which is why they’ve always been difficult to track down, you won’t see any mention of them in an index or table of contents. Despite this, issue 107 really ought to be called the flatbug issue. Once you’ve read about the breeding habits of the creatures you start seeing more of them on the pages that follow, even those by artists other than Jaffee; the last of the bugs appears on Jaffee’s fold-in page. This has some precedent in the tiny Sergio Aragones cartoons that appeared in the page margins but I’ve not seen any other one-off gags used like this. Jaffee is lauded for his fold-ins but this shows him playing with the form of the magazine in a different way, suggesting that these were real creatures, albeit motionless and almost two-dimensional.

I only got to see issue 107 a few years ago when scanned copies of the magazine began to turn up online. Prior to this I knew the flatbugs from one of the reprint books which were all you got to see of older copies of Mad magazine outside the US. I might never have seen these either if it wasn’t for a friend at school who collected humour paperbacks. He had a huge stock of the things, not only the Mad books but many of their spin-offs by Al Jaffee, Don Martin and co. The book with the flatbugs, Rip Off Mad, dates from 1973 but most of the material inside is from the previous decade. I’ve not seen a copy of this since the 1970s but I know that the bugs spread throughout the book just as they did in the magazine, even though the contents were different to issue 107.

In 2003 the flatbugs came to mind when I was writing my entry for the Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric and Discredited Diseases. My disease, “Printer’s Evil”, is a fungal growth that infects paper, and thereby passes to anyone who touches an affected page. The entry itself was, of course, contaminated in this way. Ideally one of the pages for this section would have had a frayed edge but there wasn’t the budget for such indulgence. If you do have the budget then the possibilities expand for humorous invention. The first Monty Python book, Monty Python’s Big Red Book, features a die-cut page (below), while Eric Idle’s Rutland Dirty Weekend Book has a parody of Rolling Stone magazine (Rutland Stone) printed on smaller-sized newsprint pages bound into the centre of the book. The Python books were developing a convention established by Mad (and continued in National Lampoon) of parodying print media in exacting detail, matching fonts, layouts, graphics and so on. (See this article.)

From the Python books. Left: Monty Python’s Big Red Book (1971); right: The Brand New Monty Python Bok (1973).

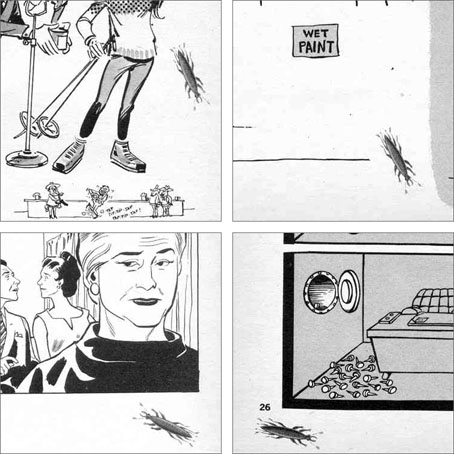

The pinnacle in this sphere is The Brand New Monty Python Bok, with its smudged fingerprints printed on a white dust-jacket (which prompted complaints from booksellers), beneath which you find a cover for a very different book, Tits ’n Bums: A Weekly Look at Church Architecture, a cover that must cause problems for resale if the dust-jacket is missing. Inside the book there’s a tipped-in library card showing the names and signatures of previous owners, while two differently-sized supplemental sections are bound into the pages. In the early 1960s Terry Gilliam had worked for Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! magazine so there’s a direct line from Python back to Mad, especially when other artists on the Help! staff included Mad regulars Al Jaffee, Jack Davis and Will Elder; Kurtzman and Gilliam subsequently collaborated on a puzzle book where the graphics and the humour sit mid-way between Mad and Monty Python. The Mad-like quality of The Brand New Monty Python Bok is reinforced by a pair of Gilliam comic strips. Jaffee’s flatbugs would be (immovably) at home there.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Blivets

• The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

• Gilliam’s shaver and Bovril by electrocution

• Portuguese Diseases

• Pasticheur’s Addiction