On Tuesday, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said administration critics suffered from “moral or intellectual confusion.” American TV commentator Keith Olbermann responds. My earlier opinion of Mr Rumsfeld can be seen here.

On Tuesday, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said administration critics suffered from “moral or intellectual confusion.” American TV commentator Keith Olbermann responds. My earlier opinion of Mr Rumsfeld can be seen here.

The man who sees absolutes, where all other men see nuances and shades of meaning, is either a prophet, or a quack.

Donald H. Rumsfeld is not a prophet.

Mr. Rumsfeld’s remarkable speech to the American Legion yesterday demands the deep analysis—and the sober contemplation—of every American.

For it did not merely serve to impugn the morality or intelligence—indeed, the loyalty—of the majority of Americans who oppose the transient occupants of the highest offices in the land. Worse, still, it credits those same transient occupants—our employees—with a total omniscience; a total omniscience which neither common sense, nor this administration’s track record at home or abroad, suggests they deserve.

Dissent and disagreement with government is the life’s blood of human freedom; and not merely because it is the first roadblock against the kind of tyranny the men Mr. Rumsfeld likes to think of as “his” troops still fight, this very evening, in Iraq.

It is also essential. Because just every once in awhile it is right and the power to which it speaks, is wrong.

In a small irony, however, Mr. Rumsfeld’s speechwriter was adroit in invoking the memory of the appeasement of the Nazis. For in their time, there was another government faced with true peril—with a growing evil—powerful and remorseless.

That government, like Mr. Rumsfeld’s, had a monopoly on all the facts. It, too, had the “secret information.” It alone had the true picture of the threat. It too dismissed and insulted its critics in terms like Mr. Rumsfeld’s—questioning their intellect and their morality.

That government was England’s, in the 1930s.

It knew Hitler posed no true threat to Europe, let alone England.

It knew Germany was not re-arming, in violation of all treaties and accords.

It knew that the hard evidence it received, which contradicted its own policies, its own conclusions—its own omniscience—needed to be dismissed.

The English government of Neville Chamberlain already knew the truth.

Most relevant of all—it “knew” that its staunchest critics needed to be marginalized and isolated. In fact, it portrayed the foremost of them as a blood-thirsty war-monger who was, if not truly senile, at best morally or intellectually confused.

That critic’s name was Winston Churchill.

Sadly, we have no Winston Churchills evident among us this evening. We have only Donald Rumsfelds, demonizing disagreement, the way Neville Chamberlain demonized Winston Churchill.

History—and 163 million pounds of Luftwaffe bombs over England—have taught us that all Mr. Chamberlain had was his certainty—and his own confusion. A confusion that suggested that the office can not only make the man, but that the office can also make the facts.

Thus, did Mr. Rumsfeld make an apt historical analogy.

Excepting the fact, that he has the battery plugged in backwards.

His government, absolute—and exclusive—in its knowledge, is not the modern version of the one which stood up to the Nazis.

It is the modern version of the government of Neville Chamberlain.

But back to today’s Omniscient ones.

That, about which Mr. Rumsfeld is confused is simply this: This is a Democracy. Still. Sometimes just barely.

And, as such, all voices count—not just his.

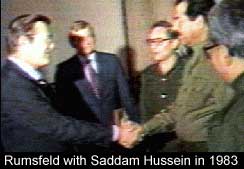

Had he or his president perhaps proven any of their prior claims of omniscience—about Osama Bin Laden’s plans five years ago, about Saddam Hussein’s weapons four years ago, about Hurricane Katrina’s impact one year ago—we all might be able to swallow hard, and accept their “omniscience” as a bearable, even useful recipe, of fact, plus ego.

But, to date, this government has proved little besides its own arrogance, and its own hubris.

Mr. Rumsfeld is also personally confused, morally or intellectually, about his own standing in this matter. From Iraq to Katrina, to the entire “Fog of Fear” which continues to envelop this nation, he, Mr. Bush, Mr. Cheney, and their cronies have—inadvertently or intentionally—profited and benefited, both personally, and politically.

And yet he can stand up, in public, and question the morality and the intellect of those of us who dare ask just for the receipt for the Emporer’s New Clothes?

In what country was Mr. Rumsfeld raised? As a child, of whose heroism did he read? On what side of the battle for freedom did he dream one day to fight? With what country has he confused the United States of America?

The confusion we—as its citizens—must now address, is stark and forbidding.

But variations of it have faced our forefathers, when men like Nixon and McCarthy and Curtis LeMay have darkened our skies and obscured our flag. Note—with hope in your heart—that those earlier Americans always found their way to the light, and we can, too.

The confusion is about whether this Secretary of Defense, and this administration, are in fact now accomplishing what they claim the terrorists seek: The destruction of our freedoms, the very ones for which the same veterans Mr. Rumsfeld addressed yesterday in Salt Lake City, so valiantly fought.

And about Mr. Rumsfeld’s other main assertion, that this country faces a “new type of fascism.”

As he was correct to remind us how a government that knew everything could get everything wrong, so too was he right when he said that—though probably not in the way he thought he meant it.

This country faces a new type of fascism—indeed.

Although I presumptuously use his sign-off each night, in feeble tribute, I have utterly no claim to the words of the exemplary journalist Edward R. Murrow.

But never in the trial of a thousand years of writing could I come close to matching how he phrased a warning to an earlier generation of us, at a time when other politicians thought they (and they alone) knew everything, and branded those who disagreed: “confused” or “immoral.”

Thus, forgive me, for reading Murrow, in full:

“We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty,” he said, in 1954. “We must remember always that accusation is not proof, and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law.

“We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men, not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes that were for the moment unpopular.”

And so good night, and good luck.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Good Night and Good Luck