Frank Miller and 300‘s Assault on the Gay Past.

No sex please, we’re Spartans.

Category: {film}

Film

The Surrealist Revolution

The riddle of the rocks by Jonathan Jones

It was the art movement that shocked the world. It was sexy, weird and dangerous—and it’s still hugely influential today. Jonathan Jones travels to the coast of Spain to explore the landscape that inspired Salvador Dalí, the greatest surrealist of them all.

The Guardian, Monday March 5, 2007

I AM SCRAMBLING over the rocks that dominate the coastline of Cadaqués in north-east Spain. They look like crumbling chunks of bread floating on a soup of seawater. Surreal is a word we throw about easily today, almost a century after it was coined by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Yet if there is anywhere on earth you can still hope to put a precise and historical meaning on the “surreal” and “surrealism”, it is among these rocks. To scramble over them is to enter a world of distorted scale inhabited by tiny monsters. Armoured invertebrates crawl about on barely submerged formations. I reach into the water for a shell and the orange pincers of a hermit crab flick my fingers away.

The entire history of surrealism—from the collages of Max Ernst to Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone—can be read in these igneous formations, just as surely as they unfold the geological history of Catalonia.

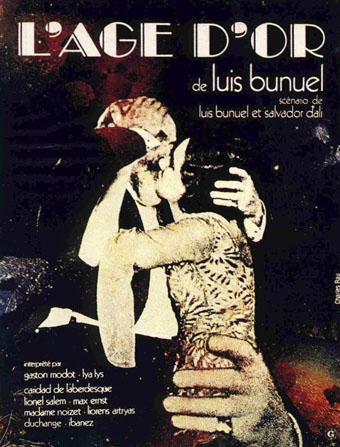

I sit down on a jagged ridge. What if I fell? Would they find a skeleton looking just like the bones of the four dead bishops in L’Age d’Or, the surrealist film Luis Buñuel shot here in 1930?

Buñuel had been shown these rocks by his college friend Dalí years earlier. It was here they had scripted their infamous film Un Chien Andalou. Dalí came from Figueras, on the Ampurdán plain beyond the mountains that enclose Cadaqués, and spent his childhood summers here, exploring the rock pools and being cruel to the sea creatures. In most people’s eyes, this is a beautiful Mediterranean setting. It certainly looked lovely to Dalí’s close friend, the poet Federico García Lorca, when Dalí brought him here in the 1920s: in his Ode to Salvador Dalí, Lorca lyrically praises the moon reflected in the calm, wide bay…

Continues here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie

David Lynch in Paris

Major art exhibition at the Cartier Foundation opens today.

And while we’re on the subject, let’s not forget Inland Empire.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Inland Empire

Crossed destinies: when the Quays met Calvino

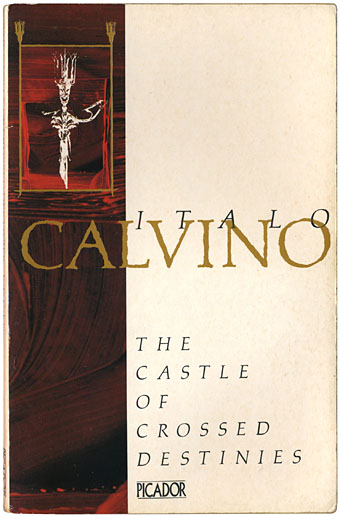

The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1986).

The Brothers Quay are known mainly for their incredible animated films but in the 1980s they were also working as book illustrators and stage designers. Today’s secondhand find was one of their paperback designs for Italo Calvino, part of a series they produced for Picador when the books were reprinted after his death. This is the first time I’ve seen this edition of The Castle of Crossed Destinies, it seems to be more common in an earlier version showing some of the Tarot cards that appear inside the book and which inspire its tales.

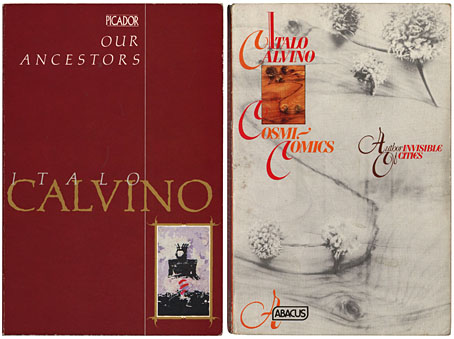

Information about this aspect of the Quays’ work is virtually non-existent so I’ve yet to discover how many covers they did in this series. Or, indeed, whether their later Abacus cover (below) was a reprint of the early designs or a new one altogether. Picador had a great run of covers in the 1980s, some of which can be better than the books they decorate. But more often than not they hit on a great design and a great book, as with these pairings.

left: Our Ancestors (1986); right: Cosmicomics (1987).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The Quay Brothers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Tressants: the Calvino Hotel

Jordan Belson on DVD

Samadhi (1967).

“Jordan Belson is one of the greatest artists of visual music. Belson creates lush vibrant experiences of exquisite color and dynamic abstract phenomena evoking sacred celestial experiences.” William Moritz

Good things come to those who wait. Following their collection of Oskar Fischinger films, the Center for Visual Music releases Jordan Belson: 5 Essential Films in March. Fischinger worked on Fantasia and Belson also exerted some small influence on Hollywood with the special sequences he created for Donald Cammell’s Demon Seed (imaginings of the film’s Proteus computer) and Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (the vortex seen by Sam Shephard at the edge of the stratosphere). You can read more about Belson’s work in Expanded Cinema by Gene Youngblood, an essential guide to film outside the narrative mainstream.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive