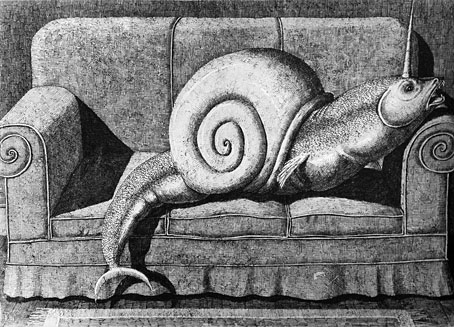

Untitled etching by Briony Morrow-Cribbs.

• An interview with author Paul Russell whose new novel, The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov, concerns the gay brother of the celebrated Vladimir.

• Joseph Cornell turns up again in a report at Strange Flowers about Locus Solus, an exhibition in Madrid devoted to the work of Raymond Roussel.

• Night of Pan: 42 seconds of occult freakery by Bill Butler featuring Vincent Gallo, Twiggy Ramirez plus (blink and you miss him) Kenneth Anger.

• Jan Svankmajer talks (briefly) about his new film Surviving Life. A subtitled trailer is here; the very different Japanese trailer is here.

• Cormac McCarthy turns in his first original screenplay. I’d rather he turned in a new novel but any new Cormac is better than none at all.

• Barnbrook show off another design for the latest CD from John Foxx & The Maths.

• Melanie McDonagh asks “Where have all the book illustrators gone?”

• Congrats to Evan for getting his poetry in the New York Times.

• Margaret Atwood on writing The Handmaid’s Tale.

• Subliminal Frequencies: An Interview With Pinch.

• The (Lucas) Cranach Digital Archive

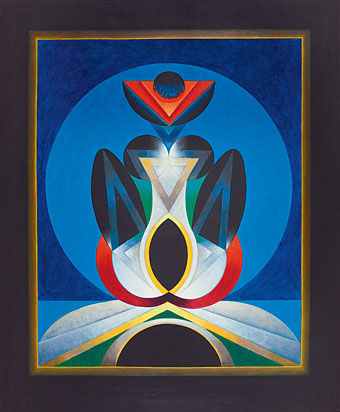

• The M.O.P. Radionic Workshop

• Music promos of the week from the Weird Seventies: All The Years Round (1972) by Amon Düül II, and Supernature (1977) by Cerrone.