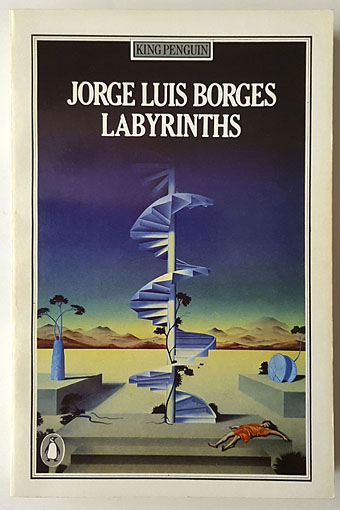

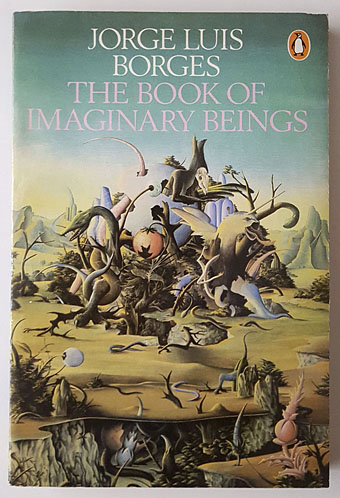

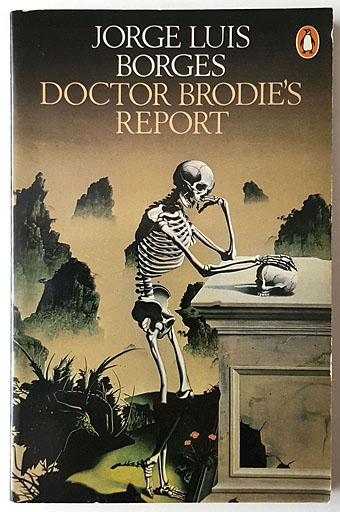

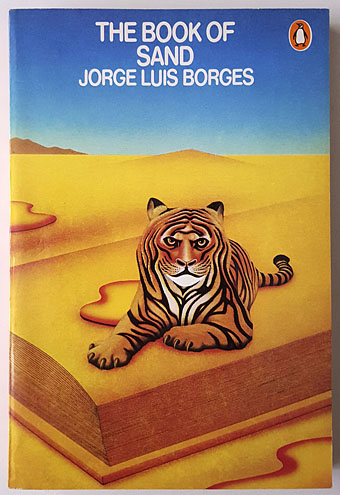

Last week’s story search had me looking through this handful of Penguin volumes again, all of which have cover illustrations by Peter Goodfellow. These were the first Borges books I bought, beginning with the Labyrinths collection in 1985. The Book of Sand is two volumes in one—The Book of Sand and a late poetry collection, The Gold of the Tigers—with cover art suitable for both. I used to think that the covers of the other books were pastiching or quoting well-known artists but now I’m not so sure. Two of them definitely are quotes or pastiches: The Book of Imaginary Beings is a play on the weird growths you find in Hieronymus Bosch, while Doctor Brodie‘s contemplative skeleton is from the famous anatomical engravings in De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius, with some Chinese or Japanese landscape details added to the background.

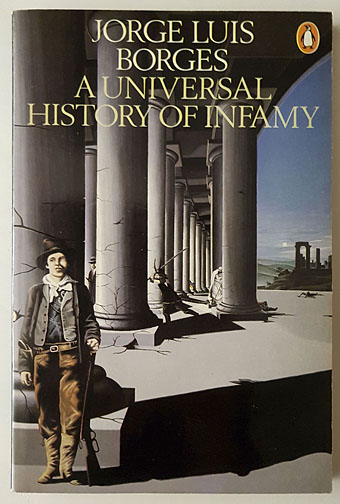

Two positive artistic references suggested that the other covers might follow suit, so I used to take the Labyrinths cover as a vague reference to the anomalies that Salvador Dalí would situate in his desert vistas, while A Universal History of Infamy was de Chirico, perhaps, although this no longer seems certain at all. Those columns look like Bernini’s double colonnade from Saint Peter’s Square in Rome, not a Turin arcade, and the picture lacks the disjunctive perspectives you find in de Chirico’s “Metaphysical” paintings. The pastiche thesis is further diluted when you discover that Goodfellow had been quoting from Bosch as far back as his cover for Ursula Le Guin’s Rocannon’s World in 1972, while he borrowed another skeleton from Vesalius for Structures by JE Gordon. Sometimes you can reach too far for meaningful connections.

The Bosch-like cover does seem to have had an enduring influence, however. When Penguin published the Collected Fictions in the UK in 1999 they used a detail from Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights for the artwork. Bosch details turned up on a later edition of A Universal History of Infamy, and have subsequently appeared on a series of Turkish Borges editions. Not a bad choice for a writer whose fictions offer universes of possibility.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Rejected Sorcerer

• The Immortal by Jorge Luis Borges

• Borges on Ulysses

• Borges in the firing line

• La Bibliothèque de Babel

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• The Library of Babel by Érik Desmazières

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance