No, not a post about a new psychedelic band but two body-oriented artworks in the news.

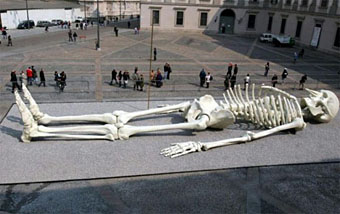

The giant skeleton by Gino De Dominicis is on display in the Palazzo Reale in Milan. More pictures at the Wooster Collective and also here. Via Towleroad.

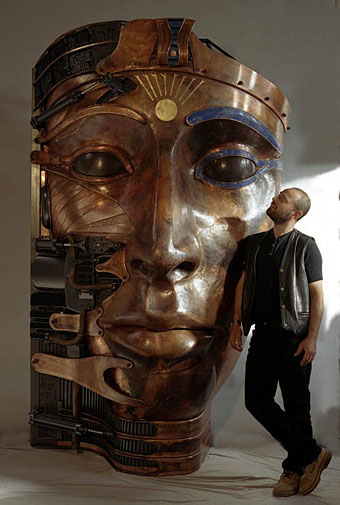

Cosimo Cavallaro‘s My Sweet Lord is due to go on display at Manhattan’s Lab Gallery in New York City on Monday but complaints from the usual suspects are giving the gallery second thoughts. More on that here. It’s okay to make any number of Messiahs from wood, stone, metal or plastic, just don’t dare make a Jesus out of anything edible.

Update: the Lab Gallery showing of the edible Jesus has been cancelled.

Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, said the work was a direct assault on Christians. “All those involved are lucky that angry Christians don’t react the way extremist Muslims do when they’re offended.”

Don’t be shy Bill, you know you’re itching to bring back the Inquisition. So Christians are angry are they? Isn’t that one of the Seven Deadly Sins? Another complaint was that Jesus is shown naked, something that we see in plenty of paintings depicting him as a child. Oh well, the artist and gallery owners can feel relieved they weren’t stabbed or shot for their pains and the forces of Righteous Wrath can file into church at the weekend to eat the body of Christ. You know, like they do every Sunday.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Very Hungry God

• Gay for God

• History of the skull as symbol