The Sopranos begins its final season tonight. Below, Annie Leibovitz swipes from Delacroix in an earlier cast photo for season 5.

The Barque of Dante by Eugène Delacroix (1822).

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Painting

The Sopranos begins its final season tonight. Below, Annie Leibovitz swipes from Delacroix in an earlier cast photo for season 5.

The Barque of Dante by Eugène Delacroix (1822).

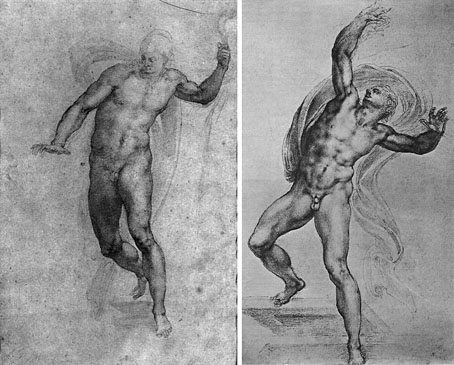

Two Studies for the Risen Christ by Michelangelo (both 1533).

Following the predictable outrage over Cosimo Cavallaro’s My Sweet Lord, aka the Chocolate Jesus, it’s worth remembering that the depiction of Jesus sans clothing is nothing new. Aside from all the paintings of Jesus as a naked infant, a quick search turns up these two examples by Michelangelo. The drawing on the right is owned by the Head of the Church of England (ie: Queen Elizabeth II) who—so far as we know—seems to have no trouble contemplating a naked Christ. Puritan factions among Christians baulk at nudity of any sort but it was Catholics who seemed to voice the strongest objection to Cavallaro’s work despite Pope John Paul II writing in Love and Responsibility in 1981:

“Nakedness itself is not immodest… Immodesty is present only when nakedness plays a negative role with regard to the value of the person, when its aim is to arouse concupiscence, as a result of which the person is put in the position of an object for enjoyment.”

The early Christian church seemed to have a different attitude to nude depictions, many scenes of Jesus’s baptism show a naked Christ. Censorship came in later, as with the painting over of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel and the painting of leaves over Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The fig leaves were added three centuries after the original fresco was painted, probably at the request of Cosimo III de’ Medici in the late 17th century, who saw nudity as disgusting. During restoration in the 1980s the fig leaves were removed along with centuries of grime to restore the fresco to its original condition.

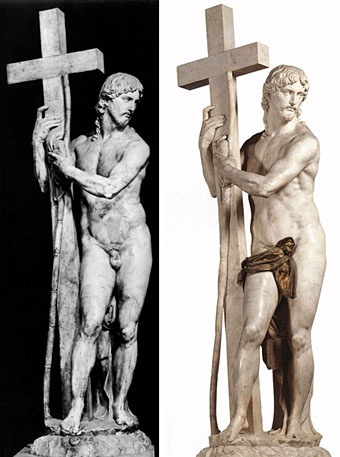

Michelangelo’s work was assaulted again during this period when an unlikely bronze wrap was attached to his statue of Christ in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.

Christ Carrying the Cross by Michelangelo (1521).

These censorious attitudes are a world away from TV presenter and art critic Sister Wendy Beckett (a Carmelite nun, no less) enthusing in Sister Wendy’s Odyssey about the “wonderfully fluffy” pubic hair in Stanley Spencer’s Self Portrait with Patricia Preece (1937). Not all Christians find nudity a problem but then people who regularly complain about art rarely look at it or even seem to like it. As George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Giant Skeleton and the Chocolate Jesus

• The Poet and the Pope

• Angels 1: The Angel of History and sensual metaphysics

• Gay for God

• Michelangelo revisited

Cadeau Audace by Man Ray (1921).

L’amour fou by Robert Hughes

Fur teacups, wheelbarrow chairs, lip-shaped sofas … the fashion, furniture and jewellery created by the Surrealists were useless, unique, decadent and, above all, very sexy.

The Guardian, Saturday March 24th, 2007

THE VICTORIA AND Albert’s big show for this year, Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design, is—well, maybe we don’t much like the word “definitive”. But it’s certainly the first of its kind.

Everyone knows something about surrealism, the most popular art movement of the 20th century. The word has spread so far that people now say “surreal” when all they mean is “odd”, “totally weird” or “unexpected”. No doubt this would give heartburn to André Breton, the pope of the movement nearly a century ago, who took the title from his friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had called his play The Breasts of Tiresias, “a surrealist drama”. But too late now. The term is many years out of its box and, through imprecision, has achieved something akin to eternal life. Surrealist painting and film, that is. In fact, some surrealist images have imprinted themselves so deeply and brightly on our ideas of visual imagery that we can’t imagine modern art (or, in fact, the idea of modernity itself) without them.

Think Salvador Dalí and his soft watches in The Persistence of Memory. Think Dalí again, in cahoots with Luis Buñuel, and the cut-throat razor slicing through the girl’s eye, as a sliver of cloud crosses the moon (actually, the eye belongs to a dead cow, but you never think this when you see their now venerable but forever fresh movie An Andalusian Dog, 1929). Think of photographer Man Ray’s fabulous Cadeau Audace (‘Risky Present’, 1921), the flatiron to whose sole a row of tacks was soldered, guaranteeing the destruction of any dress it would be used on. Think of Rene Magritte’s The Rape, that hauntingly concise pubic face, with nipples for eyes and the hairy triangle where the mouth should be. Think of the shock, the horniness, the rebellion, the unwavering focus on creative freedom, the obsessive efforts to discover the new in the old by disclosure of the hidden…

Continues here

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealist Revolution

• Surrealist Women

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Surrealist cartomancy

Pornokrates (1878).

After Mr Peacay’s comments regarding Félicien Rops I thought it time to devote a post to this impious artist.

Rops, a Belgian working in Paris, is curious even by the standards of the disparate group who comprised the Symbolists and with whom he had some connections. Whereas many artists of the time might hint at a fashionable blasphemy or Satanism, Rops’ dealings with these subjects were unequivocal, as was the outright pornographic tone of many of his drawings. This can make much of his work seem modern in a way few artists of that period achieve today, and it’s a good bet that many Christians (especially those of the puritan American variety) would still find his pictures offensive. These weren’t the only works that Rops produced, there were plenty of landscapes and society portraits, but it’s these that he’s remembered for. Once again, posterity favours the forthright and the unique over uniformity and compromise.

• The Félicien Rops Museum

• Les Diaboliques by Barbey d’Aurevilly (1874): 8 illustrations

• Gallery of pornographic drawings at Arterotismo

Still in pursuit of a Cormac McCarthy obsession I picked up a copy of the (American) Vintage International paperback of Blood Meridian this week, almost solely for the cover. As it turns out it’s also an easier book to read than the UK edition, less tightly bound although the body text in both looks as though it was printed from photocopied galley proofs. The cover design is by Susan Mitchell, with photography by Craig Arness, and forms part of a small series among the Vintage reprint editions. Mitchell resists the understandable temptation to put red on the cover, saving that for McCarthy’s tale of a murderer, Child of God.