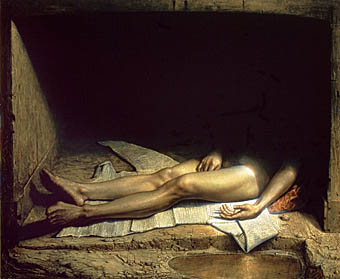

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768).

As promised, one of my favourite chiaroscurists. The impression Joseph Wright’s work made on me at the age of 13 was one of many revelations from my first visit to the Tate Gallery. The paintings which struck me most of the older works there were all of the Romantic or late-Romantic era: Turner, Francis Danby, John Martin, Philippe de Loutherbourg and Joseph Wright’s enormous An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, which is now housed in the National Gallery. The National Gallery site has this to say about the picture:

A travelling scientist is shown demonstrating the formation of a vacuum by withdrawing air from a flask containing a white cockatoo, though common birds like sparrows would normally have been used. Air pumps were developed in the 17th century and were relatively familiar by Wright’s day. The artist’s subject is not scientific invention, but a human drama in a night-time setting.

The bird will die if the demonstrator continues to deprive it of oxygen, and Wright leaves us in doubt as to whether or not the cockatoo will be reprieved. The painting reveals a wide range of individual reactions, from the frightened children, through the reflective philosopher, the excited interest of the youth on the left, to the indifferent young lovers concerned only with each other.

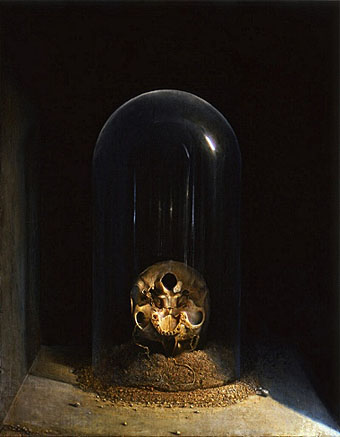

The figures are dramatically lit by a single candle, while in the window the moon appears. On the table in front of the candle is a glass containing a skull.

As with many paintings, the online reproductions do little justice to the subtlety of Wright’s rendering of light and shade. This remains his most famous picture although he made another on a similar theme, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery (below) and, like Godfried Schalcken, he has at least two studies of people viewing statues by candlelight, a common practice at that time for the way the light gave classical sculpture a spurious life. Wright’s painting of The Alchymist is another popular work, turning up frequently in occult encyclopedias. Being a native of Derby he also became (along with de Loutherbourg) one of the first painters to depict the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution whose flaring furnaces provided an ideal subject for dramatists of flame and shadow.

Before leaving the tenebral world, I’ll note that Claire left a message to say that issue 24 of Cabinet Magazine has a feature on shadows in art, symbolism and philosophy.

Continue reading “Chiaroscuro II: Joseph Wright of Derby, 1734–1797”