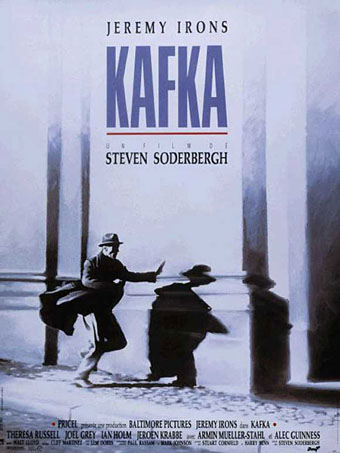

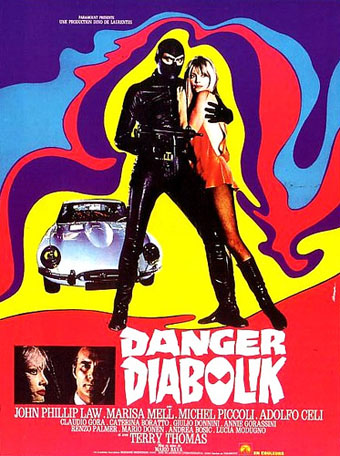

More pulp madness as Mario Bava’s 1968 crime caper finally appears on DVD in the UK this week; a camp confection from an already very camp decade, although it pales beside the lurid excesses of Barbarella which was released in the same year. Both films were based on popular European comic strips, and both are connected by the presence of John Phillip Law, the sexiest (male) screen angel in Barbarella, and the star of Danger Diabolik. Barbarella’s adventures on page and screen managed to be equally frivolous whereas master thief Diabolik in the original fumetti (which is still running) was rather more serious, at least in serial adventure terms. Bava forgoes any attempt to treat his subject with a straight face, opting instead for the knowing action-comedy style that was popular during the Sixties, whether in post-Bond fare such as Our Man Flint or superior TV series like The Avengers.

Diabolik stands apart from his contemporaries, and from other campy comic spin-offs such as Adam West’s Batman, by being an anti-hero in a field over-stuffed with costumed vigilantes and sexist super-spies. Most characters of this type are descendants of deathless arch-criminal Fantômas, and Diabolik can perhaps be seen as a trendy updating of the Fantômas type, with his black leather bondage outfit and ultra-cool E-type Jaguar, probably the only car ever made in Britain that would impress style-conscious Italians. The comic strip was created in 1962 by two sisters, Angela and Luciana Giussani, a feat one imagines would be impossible in the male-dominated world of American comics at that time.

The fumetti Diabolik shuns firearms in favour of knife-throwing expertise, something that Bava ignores by giving him a mundane machine-gun. Bava had directed a very silly James Bond spoof, Doctor Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs, two years earlier, and always had a great eye for aesthetics even when lacking an adequate budget. His horror films frequently outdid Hammer for Gothic atmosphere, and his strange science fiction/horror, Planet of the Vampires (1965), features a cast similarly sheathed in shiny black spacesuits. The clouds of coloured fog those astronauts encounter reappear as the coloured smoke Diabolik uses to evade his pursuers, while his underground super-pad is one of the more spectacular villainous residences, like something Norman Foster might design for Dr. No. It certainly makes the Batcave look shabby, although, as with all these underground complexes, you can’t help wondering who the hell built them and how they managed to escape detection while doing so. The plot of the film, such as it is, is some forgettable nonsense concerning Diabolik’s cat-and-mouse game with his chief adversary, Inspector Ginko. Michel Piccoli plays the inspector, and it’s surprising seeing the splendid Terry-Thomas as a government official who Diabolik embarrasses with “exhilarating gas” at a press conference. The film is embellished with a tremendously groovy score by Ennio Morricone.

One of my favourite comic strip heroes when I was a kid was Billy the Cat in the Beano, the adventures of a super-agile boy in a black leather catsuit (no eyebrow-raising, please). I always had a fondness for these kind of characters, and I’m sure I would have loved Danger Diabolik for the cat burglary and the Sixties’ zaniness had I seen it on TV. My only gripe now is I can’t quite believe that Diabolik is all that interested in his female companion, Eva, despite the scene where they have sex on a revolving bed covered in dollar bills. If he’d rescued Alain Delon’s taciturn assassin from death at the end of Le Samouraï he could find Eva a nice young man in Monte Carlo, after which Jef Costello (as Delon is named in Melville’s film) could whack the pesky Inspector Ginko, and the pair could live together in subterranean peace, at least until the next heist. We can but dream.

A tip of the hat to Mark Pilkington for alerting me to this one. Bava’s Diabolikal influence lives on via Roman Coppola’s 2001 homage to Sixties’ camp, CQ, and the Beastie Boys’ video for Body Movin’.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Fantômas

• The persistence of memory