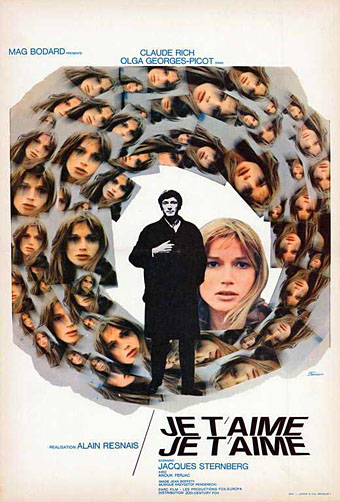

Design by René Ferracci.

Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films with a return to Alain Resnais. This one is less substantial than the Providence post, but 2022 happens to be the director’s centenary year, and this particular film, like Providence, is worthy of greater attention.

Last Year at Marienbad is occasionally proposed as science fiction of a very rarified sort (JG Ballard thought it was) but there’s no question about the SF credentials of Je t’aime, Je t’aime (1968), a drama that uses time travel to explore a troubled romantic relationship. Claude Ridder (Claude Rich), an unattached, suicidal man, is persuaded by scientists to assist with a potentially hazardous experiment. He agrees to a one-minute excursion into his past but the experiment doesn’t work as intended, causing him to be caught between the present—in which he can’t escape from a womb-like time machine—and his recent past, in which he relives brief moments without any awareness during the return period of their being a part of the experiment. The flashbacks that comprise most of the film’s running time show us a random sequence of the events leading to Claude’s suicide attempt, the end result of his relationship with his terminally ill partner, Catrine (Olga Georges-Picot).

The time machine.

Despite the presence of a time machine and a script by Jacques Sternberg, a Belgian science-fiction writer, Resnais was adamant that Je t’aime, Je t’aime wasn’t a science-fiction film. This is the kind of comment guaranteed to annoy the more zealous SF reader but it’s true in the sense that the film isn’t about time travel or time machines per se; the temporal experiment is a device to allow the non-linear exploration of a human drama that’s the real concern of director and writer. Previous Resnais films had dealt with remembrance of one sort or another, often using flash cuts to juxtapose different moments or scenes remembered or imagined. Je t’aime, Je t’aime pushes these techniques to an extreme, showing us every facet of the Claude/Catrine relationship, from initial meeting to tragic end. The narrative fragmentation isn’t so surprising today but it was a radical step in 1968, one that proved commercially unsuccessful.

In addition to having a Belgian writer, Je t’aime, Je t’aime is mostly set in Brussels, so the art this time is a famous Belgian painting, one of the many versions of The Empire of Light by René Magritte, which appears in the scenes in Claude’s apartment.

In other hands this might be an incidental decoration but, as Providence demonstrates, Resnais was a director who enjoyed significant details, even if the signification isn’t always obvious. The Magritte painting serves two functions: its slow migration from one side of Claude’s apartment to the other (and the appearance of other pictures around it) shows the passage of time from one flashback to the next.

But its presence also allows a Surrealist atmosphere to pervade the film in a handful of Buñuel-like scenes which we can only take as products of Claude’s dreams or fantasies: a woman sitting in a bathtub on a desk in Claude’s office; Claude and an unidentified woman lying in a bed while a man in the same room tries to prevent someone from coming through the door (a reverse angle of the same scene shows a different woman in the bed); a man making a phone call in a phone booth filled with water; Claude’s colleagues clustered around his desk discussing him and his work; a man in a mask (the Creature from the Black Lagoon?) opening a gate for Claude.

One of the unique qualities of this film is that the very brief nature of the flashbacks means that we’re often absorbing the sense of the words or actions in a scene when the next scene is already taking place (and the lag is compounded if you’re also reading subtitles); this allows the dream flashbacks to slide past almost without notice, something that wouldn’t be possible in a more conventional narrative. These inexplicable moments reflect the Magritte approach to Surrealism which favoured the repurposing or transformation of everyday objects; the flooded phone booth is even a precursor of an album cover created by the Magritte-inspired Hipgnosis design team in 1978 for Deadlines by Strawbs.

The painting is an unmissable reference but the same can’t be said for this blink-and-you-miss-it shot of a book cover which Claude examines after asking what Catrine has been reading. Fatala is the anti-heroine of a series of crime novels written by Marcel Allain, a female equivalent of Fantômas, the character created by Allain with Pierre Souvestre. Once again this isn’t an arbitrary reference if you know that Resnais venerated the Feuillade Fantômas serials (“Feuillade’s cinema is very close to dreams—therefore it’s perhaps the most realistic”), as did the Surrealists, especially René Magritte, several of whose paintings refer directly or otherwise to the Lord of Terror.

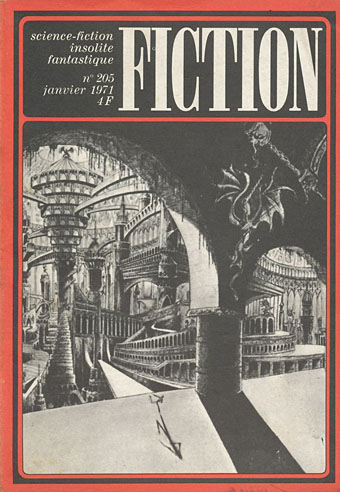

That would be all were it not for one last detail which is so vague and obscure I have to wonder (yet again…) if I’m the only person to have identified it. The drawing with the arches next to the Magritte print is never seen clearly but I’m fairly sure it’s an early piece by Philippe Druillet (and may even be the original artwork) which was used a few years later in cropped form on a cover of the French genre mag Fiction (previously).

Cover art by Philippe Druillet. Is this a Lovecraftian piece? Maybe…

Druillet’s work was becoming more prominent around this time—Jean Rollin’s Le Viol du Vampire was released in 1968 with a poster by Druillet—while Resnais always liked comics; his later films included contributions from Enki Bilal and Guy Peellaert, and in 1989 he made a feature about a cartoonist, I Want to Go Home, scripted by Jules Feiffer. Most of the Druillet drawings used on the Fiction covers are hard to find in any other form but if anyone knows of a good copy of the picture above then please leave a comment.

I said earlier that the film was unsuccessful in 1968 which may explain its subsequent and lingering neglect. I know that rights issues are tricky things but it can still be surprising to see mediocre features receiving prestige blu-ray reissues while works of art like Je t’aime, Je t’aime (which also features a minimal choral score by Krzysztof Penderecki) are marooned in the cinematic doldrums. It’s one I’d recommend if you can find it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Art on film: Space is the Place

• Art on film: Providence

• Art on film: The Beast

• Marienbad hauntings

Wasn’t that Jules Verne’s criticism of H G Wells, that he wasn’t scientific enough?

There is a Blu-Ray available here in the States with subtitles in Dutch and English, that I assume must be Region 1 since apparently it can’t be sold internationally. Unfortunately it seems to suffer from a poor transfer.

Yes, it must be the oldest argument in science fiction, between those who want to write about people and those who want to write about magic technology.

My BR player is Region 2 but that’s okay, it saves me having to fret about ordering R1 releases along with other things. Here we have access to France (not always useful since they seldom add foreign subs) and Germany, who often release things you can’t find elsewhere. The copy of the Resnais film I was watching was probably taken from the French DVD; the picture was fine but the subtitles were very sparse, I was having to mentally assist with the translation now and then.