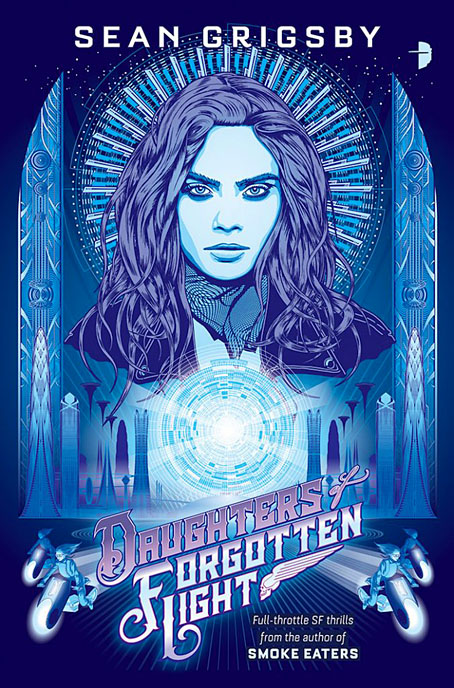

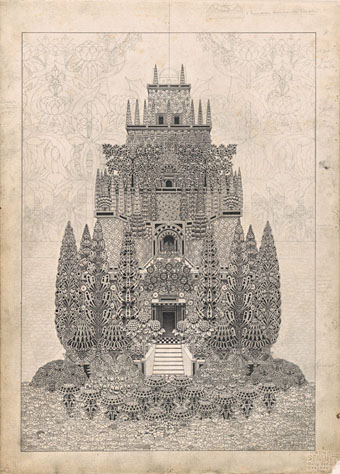

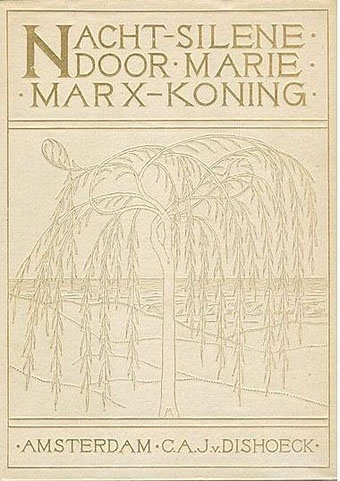

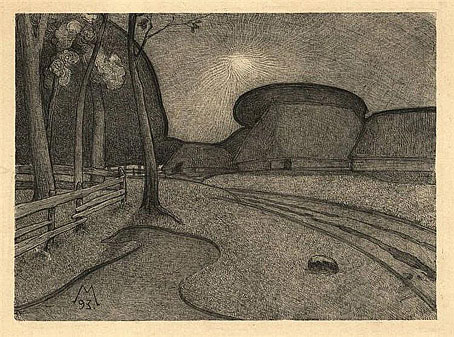

I’ve spent most of the year so far working on more black-and-white illustrations for Editorial Alma—47 full-page pieces to date—so this cover design made a welcome break, especially since all the black-and-white art has a late-Victorian setting. More about that later. Sean Grigsby’s second novel for Angry Robot Books is previewed at the Barnes & Noble SF blog as follows:

A floating prison is home to Earth’s unwanted people, where they are forgotten…but not yet dead, in this wild science fiction adventure.

Deep space penal colony Oubliette, population: scum. Lena “Horror” Horowitz leads the Daughters of Forgotten Light, one of three vicious gangs fighting for survival on Oubliette. Their fragile truce is shaken when a new shipment arrives from Earth carrying a fresh batch of prisoners and supplies to squabble over. But the delivery includes two new surprises: a drone, and a baby. Earth Senator Linda Dolfuse wants evidence of the bloodthirsty gangs to justify the government finally eradicating the wasters dumped on Oubliette. There’s only one problem: the baby in the drone’s video may be hers.

The gangs are biker gangs, riding machines with wheels of light, so the brief was for a design as much reminiscent of a rock poster as a science-fiction cover. I don’t stray very often into the SF world so this again made a refreshing break from the 19th century and its heavy furnishings. There’s a touch of Syd Mead in the background, a reference suggested by the Tron-style bikes, but he’s long been a favourite visual futurist of mine even before Blade Runner (as I noted recently). The side panels and parts of the halo are adapted from Art Deco designs, the panels being based on embellishments for a New York skyscraper. It doesn’t take much to push the aerodynamic qualities of Deco style into the Space Age (the Soviet Monument to the Conquerors of Space could have been designed in 1930), a suggestion that William Gibson explored from a different angle in The Gernsback Continuum.

The Barnes & Noble post linked above also has an extract from the beginning of the novel. The book itself will be out on 4th September, 2018.