My mother thought well enough of The Beatles in the 1960s to buy two of their albums—Beatles For Sale and Help!—and she continued to enjoy the Fab Four’s songs up to the point when (in her words) “they went funny”, by which she meant the period after Rubber Soul when they dropped the beat stylings, picked up sitars and took to recording drums and guitars in reverse. They were also taking drugs, of course, hence the funniness, and this rapid evolution—from loveable moptops to freaked-out weirdos in a matter of months—is the subject of Rob Chapman’s huge study of psychedelia as a cultural phenomenon, the period from around mid-1965 to late 1969 when Western youth “went funny” en masse.

This isn’t an undocumented era but Chapman’s book provides an overdue counterweight to the American focus of earlier studies such as Jay Stevens’ Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream (1987). Psychedelic art evolved in San Francisco but it’s an irony of the form that many of the wildest, most typically psychedelic concert posters were promoting acts that were only marginally psychedelic in their sound or, in the case of the older jazz, soul and blues acts, weren’t psychedelic at all. Chapman is more interested in the multi-media light shows than the poster art, and he reaches back in his early chapters to the origin of the San Francisco light shows in the avant-garde art of the Modernist era (especially László Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator of the 1920s) and the art schools of the 1950s; he also traces the familiar journey of LSD from the Sandoz laboratories in Switzerland and the clinics of America to the front pages of newspapers and magazines. One of the most remarkable and unlikely aspects of psychedelia was the way in which a short-lived poly-cultural phenomenon maintained an aura of danger and illegality late into the 1960s even while psychedelic aesthetics were filtering into every facet of mainstream life: films, fashion, decor, advertising, even children’s television—all bloomed briefly with vivid colours and melting typography.

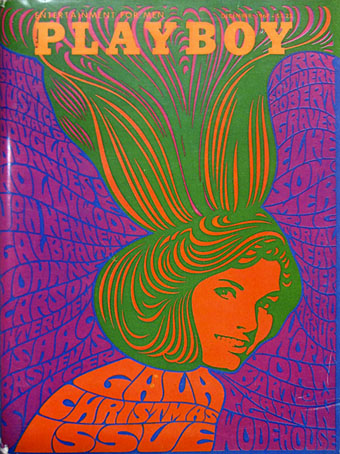

Playboy gets hip to the trip, December 1967. Art by Wes Wilson.

Chapman touches on all of this but the bulk of his study is concerned with the music which was always the core of psychedelic culture, even if many of the artists involved were only following a trend (or, to be less charitable, jumping on a bandwagon). American groups are given their due, and Chapman has some smart things to say about the often neglected surf boom of the early 60s; as noted here last month, the first piece of popular music to use “LSD” in its title was LSD-25 (1960), a surf instrumental by The Gamblers. Surf bands and garage bands mutated into psychedelic groups but there was often little change in the overall sound beyond adding an effect or two to the instrumentation. Adulterated or processed sound is what I usually look for in psychedelic music, the psychedelic experience being one of distorted or exaggerated perception. Adulteration (or lack of it) is the most obvious factor that differentiates American psych from its British equivalent: White Rabbit by Jefferson Airplane is a great song (its final line is fixed to every page of this blog) but is psychedelic only as a result of its lyrical context. Musically, the song is a simple rock bolero next to which Strawberry Fields Forever sounds like a broadcast from another planet.

The key difference, as Chapman notes in his discussion of the San Francisco scene, is that the American groups were predominantly live acts who tended to import their concert act to the recording studio. Bands in Britain couldn’t avoid the gravitational mass of The Beatles whose use of the studio as an instrument produced a wealth of unusual audio effects that were immediately imitated and recycled. Studio processing quickly became the default mode for British bands, and it’s significant that one of the most sonically adventurous American musicians of the period—Jimi Hendrix—recorded his music in London. The other major difference between London (British psych only ever means London) and the West Coast was a glut of chart-chasing singles released by the UK labels. Overproduction led to a pursuit of novelty, and the astonishing range of that novelty has been mapped across a seemingly endless run of compilation albums ever since.

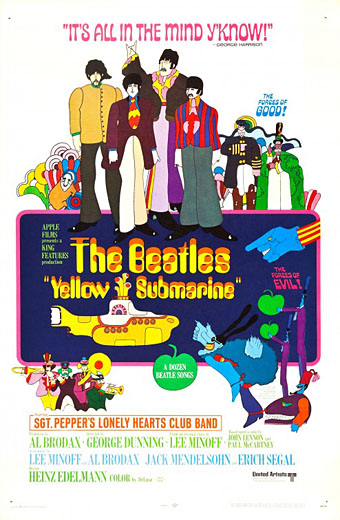

Discussion of The Beatles is unavoidable in a book of this nature. It’s always fascinated me that for the space of a year the most successful group in the world embraced psychedelia completely while rivals like The Who and The Rolling Stones could only dabble a little before turning back to more familiar rock’n’roll forms. Chapman devotes a chapter to The Beatles which focusses exclusively on their acid songs. Here he argues for The Beatles being more of a group for uncritical kids than hip adults, many of whom could be dismissive about the Fab Four’s omnipresence, their teenybopper legacy and the inflated claims made for their songs by musicologists. Chapman was a teenager in the 1960s so he’s writing from experience but the argument makes sense to me even though I was too young to pay attention at the time. The earliest I remember is the very end when they played on the roof of the Apple building then promptly split up; but psychedelia—again, despite the drug connotations—was immediately attractive to kids, and I became a convert by watching populist spin-offs like Yellow Submarine and Smashing Time when they appeared on TV a few years later. Everyone at school could sing the chorus of Yellow Submarine even if they didn’t know any other Beatles songs, and many childhood friends had one of the Yellow Submarine toys that Corgi produced in 1969.

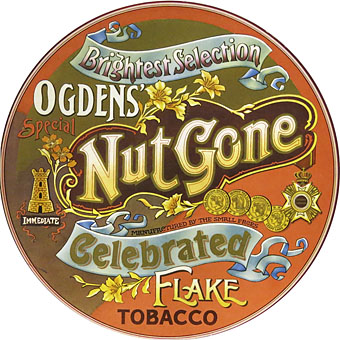

Prime British psychedelia, and an innovative sleeve design: Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake (1968) by The Small Faces.

The child-oriented quality of British psych is another hallmark that separates it from its American counterpart. US groups were writing songs during a period of great national turmoil with race riots, assassinations and the war in Vietnam a constant background to all the declarations of love and peace (a disparity satirised by The Mothers of Invention on We’re Only In It For The Money). British psych is often a long way from global strife and its blues and rock’n’roll precursors. Many of the psych groups may have been Mods who swapped their suits and scowls for paisley and beads but the musical setting was flexible enough to draw upon sources that had been almost totally eclipsed by the advent of rock’n’roll, not least the music-hall tradition. Chapman devotes separate chapters to a great deal of previously unexplored terrain, looking at the music-hall influence, the peculiar strain of First World War nostalgia, the prevalence of “infantasia” (all the songs about circuses, toys, model villages, sweets, ice cream and childhood in general), raga rock and sitar exotica, and the stuff that other critics usually avoid altogether: psych-kitsch, a crucial component of the British scene which was often happily insincere in its exploitation of prevalent drug metaphors. This is familiar territory to anyone who’s ploughed through all 20 discs of Bam-Caruso’s Rubble collection but it’s a period of musical history that’s been buried by the repudiation of psychedelic excess in the 1970s, and the subsequent quest—in America at least—for a spurious musical authenticity. I have even less time than Chapman does for all the born-again country rock of the early 70s, a style that he acerbically notes was just as inauthentic as the often ersatz grooviness it replaced. British music couldn’t go country in the same way so it got heavier and more complex, hence progressive rock which is not only a natural evolution of psychedelia’s aural and conceptual wrangling but was also an exclusively British development. Chapman doesn’t follow this evolution but I’d have been happy to continue reading if he had.

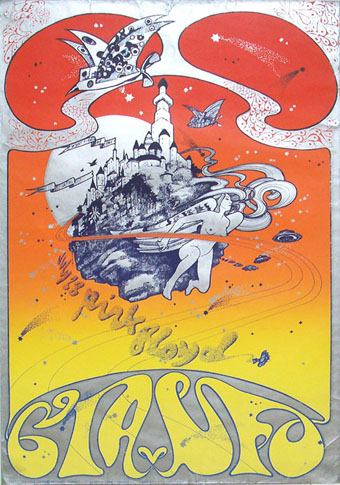

CIA–UFO (1967). Pink Floyd poster by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat.

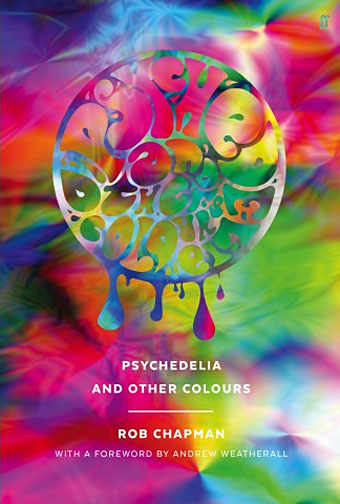

This is a fascinating book by an excellent guide, one of the few volumes where I’d expect to find mention of Boeing Duveen And The Beautiful Soup, and sure enough they’re there on page 504 in a discussion of the influence of Lewis Carroll on the British bands. There are no pictures at all in these pages of double-columned text but there’s no padding either, and the visual component of psychedelia has in any case been covered extensively elsewhere. (I’d recommend High Art: A History of the Psychedelic Poster [1999] by Ted Owen, Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era [2005] by Christoph Grunenberg, and Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art [2012] by Norman Hathaway & Dan Nadel.) For an example of Chapman’s encyclopedic knowledge of musical obscurities look no further than his psych-pop playlist compiled for Mojo magazine in June 1997, an amazing combination of novelty hits, unlikely pop one-offs and a few choice film moments, notably Bedazzled and Love Power. Even if the songs are unfamiliar the descriptions are a treat in themselves.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• LSD-25 by The Gamblers

• More trip texts

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part Six

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part Five

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part Four

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part Three

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part Two

• Listen to the Colour of Your Dreams: Part One

• Trip texts

• Acid albums

• Acid covers

• Lyrical Substance Deliberated

• The Art of Tripping, a documentary by Storm Thorgerson

• What Is A Happening?

• My White Bicycle

• Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake

• Tomorrow Never Knows

• Enter the Void

• In the Land of Retinal Delights

• Smashing Time

• The Dukes declare it’s 25 O’Clock!

• A splendid time is guaranteed for all

• The art of LSD

• Hep cats

I remember having a discussion with the psychogeographer extraordinaire Philip Legard years ago about the symbolism of penny-farthings (and other kind of bicycles) in the British psychedelic culture. I cannot recall if we reached a definitive conclusion, but I think Phil suggested it had to do something with the peculiar nostalgia about the Victorian/Edwardian times.

Co-incidentally (?) I stumbled across the following photography of Sir James Melville Babington today and immediately thought that it must’ve been the inspiration for those “Sgt. Pepper” cut outs:

http://armylists.org.uk/images/babington.JPG

How bizarre to notice that perhaps the most iconic piece of British psychedelic album art has reference to the Second Boer War!

Must say that Rob Chapman’s Syd Barrett biography was such a pleasure to read after all those “Mad Syd” hackographies and it still is one of my all-time favorite music books. This new one looks no less intriguing.

The nostalgia seemed in part to be a reaction to mid-century Modernism, a harking back to more florid fashions and styles that for decades had been regarded as unacceptable in the post-Bauhaus world. So it was a cyclical thing, a new generation taking a fresh look at things their parents rejected. The Beardsley revival began with an exhibition at the V&A in 1966, and that coincided with a general revival of interest in both Art Nouveau and Art Deco. There’s also a material reason in that the antique shops in 60s London were full of cheap Victorian and Edwardian clothes and decorative materials. The drugs created a taste for elaborate decoration which the shops were able to supply.