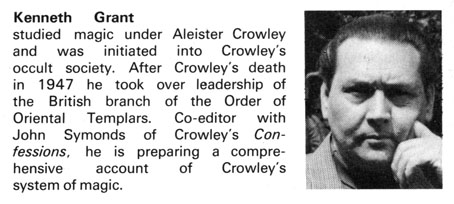

Going through some of my loose copies of Man, Myth and Magic recently turned up this article by Kenneth Grant that I’d forgotten about. I have two separate sets of Man, Myth and Magic: a complete edition in binders, and a partial collection of loose copies of the weekly “illustrated encyclopedia of the supernatural”. The partial collection is worth keeping for the unique articles that ran across the last two pages of every issue, all of which are absent (along with the magazine covers) from the bound edition. These articles formed the Frontiers of Belief series, a collection of essays of the kind one might find in magazines today such as Fate or Fortean Times. An earlier essay about Wilfried Sätty, Artist of the Occult, was reproduced here a few years ago; none of these pieces have ever been reprinted so it seems worthwhile putting another of the more interesting pieces online.

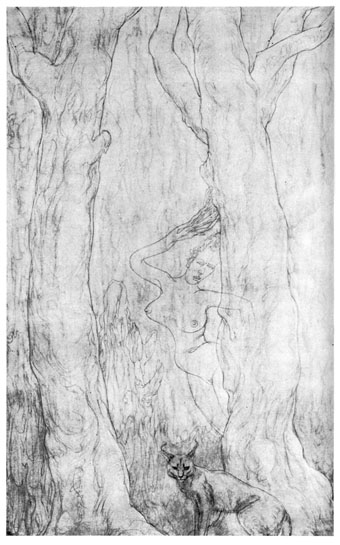

Kenneth Grant was the only active occultist among Man, Myth and Magic‘s roster of very serious and well-regarded writers and experts. Grant wrote several of the encyclopedia entries although not the one about Aleister Crowley, as you might expect, that entry going to Crowley’s executor and biographer, John Symonds. Grant was also a lifelong champion of HP Lovecraft’s fiction which explains this article; many of Grant’s later occult texts have a distinctly Lovecraftian flavour, and they often refer to Lovecraft and Arthur Machen as being the unconscious recipients of actual occult emanations or presences. Grant’s belief that the authors channelled these emanations into their fiction is central to this piece, a belief that Lovecraft would have dismissed even though several of his stories (not least The Call of Cthulhu) concern exactly this process. Grant connects Lovecraft with another artist whose work he championed throughout his life, Austin Osman Spare. It was Grant’s involvement with Man, Myth and Magic that put one of Spare’s drawings on the cover of the first issue, and further drawings inside the magazine, introducing the artist’s work to a new, highly receptive audience. The drawing below (Were-Lynx) appears in the magazine behind Grant’s text so I’ve scanned a text-free copy from Grant’s Cults of the Shadow (1975).

•

DREAMING OUT OF SPACE by Kenneth Grant

Malevolent powers are lurking in wait to project themselves into the sleeping minds of men: this terrifying idea is a recurring theme in the stories of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who claimed that they came to him in nightmares. But were they simply bad dreams, or was he in fact receiving communications from an unknown source, as Kenneth Grant here suggests?

“I have watched for dryads and satyrs in the woods and fields at dusk”; illustration by Austin Osman Spare, who sensed the forces looming behind Lovecraft’s work, and was inspired to illustrate these presences.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft died in 1937; but the myth-cycle which he initiated in unrivalled tales of cosmic horror now raises the question whether it was a mere fiction engendered in the haunted mind of an obscure New England writer, or whether it foreshadowed a particularly sinister kind of occult invasion.

According to a well-known occult tradition, when Atlantis was submerged, not all perished. Some took refuge on other worlds, in other dimensions; others “slept” a willed and unnatural sleep through untold aeons of time. These awakened; they lurk now in unknown gulfs of space, the physical mechanism of human consciousness being unable to pick up their infinitely subtle vibrations. They lurk, waiting to return and rule the whole earth, as was their aim before the catastrophe that destroyed their corrupt civilization.

This tradition was a major theme in Lovecraft’s work. Until quite recently people read his stories and shuddered (if sufficiently honest and sensitive enough to admit their uncanny impact), not suspecting for a moment that such things could be.

Few know that Lovecraft dreamed most of his tales. And he sometimes thought that these dreams, or rather, nightmares, were caused by misdeeds in remotely distant incarnations when, perhaps, he had aimed at acquiring magical powers. These dreams were memories of the past and prophecies of the future, for he said that “nightmares are the punishment meted out to the soul for sins committed in previous incarnations—perhaps millions of years ago!”

In his life as Howard Phillips Lovecraft he tried again and again to bring himself to face squarely the ordeal through which he knew he would have to pass, if he were finally to resolve his spiritual difficulties. The issue is brought to the surface perhaps more clearly and urgently in his poems than in his stories. He is on the brink of making the critical discovery, of surprising the secret of his inner life, and he is forced back repeatedly by the dread, the stark soul-searing fear which he bottles up in his work and which he communicates so successfully—in neat doses—to his readers.

One of Lovecraft’s most vivid creations is the ancient book of hideous spells composed to facilitate traffic with creatures of unseen worlds. He ascribed its authorship to Abdul Alhazred, a mad Arab who flourished in Damascus about 700 AD. This grimoire, during the course of its mysterious career, is supposed to have been translated by the Elizabethan scholar Dr John Dee, into Greek, under the title of Necronomicon. It contains the Keys or Calls that unseal forbidden spaces of cosmic sleep, inhabited by elder forces that once infested the earth. The Keys are in a wild, unearthly tongue reminiscent of the Calls of Chanokh, or Enoch, which Dr Dee actually obtained through contact with non-terrestrial entities during his work with the magician, Sir Edward Kelley, whom Aleister Crowley claimed to have been in a previous life. It is possible that the “evil and abhorred Necronomicon” was suggested by the clavicles or Keys of Enoch, which Dee and Kelley discovered, and which Crowley later used to gain access to unknown dimensions.

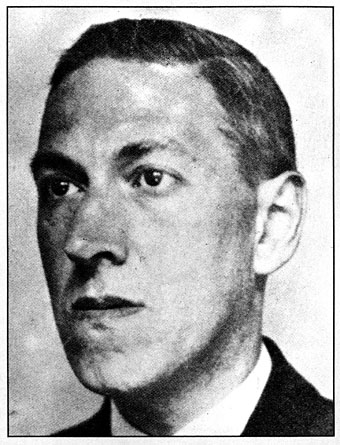

Howard Phillips Lovecraft: he dreamed most of his tales, and sometimes thought these nightmares were caused by misdeeds in past incarnations.

Appalling Visions

Although Lovecraft seems to have been unacquainted with Crowley’s work, it is evident that both were in touch with a source of power, “a praeter-human Intelligence”, capable of inspiring very real apprehension in the minds of those who were, either through past affiliation or present inclination, on the same wavelength. Whether this Intelligence is called Alhazred or Aiwaz (both names, strangely enough, evoking Arab associations) we are surely dealing with a power that is seeking ingress into the present life cycle of the planet. Lovecraft approached the very core of the matter in a way only possible to an artist of extreme sensitivity to occult forces, though the conscious part of him protested strongly against the belief in their validity. He protested in vain, for his work reveals in every line the fear-imbued phantom of the vast and ancient memories that haunted him.

In case anyone thought that his appalling visions were drug-induced, Lovecraft stated categorically that “as a rule, I avoid taking drugs to stimulate literary endeavour”, and he wrote, regarding de Quincey, the author of Confessions of an Opium Eater. “I never took opium, but if I can’t beat him for dreams from the age of three or four up. I am a dashed liar! Space, strange cities, weird landscapes, unknown monsters, hideous ceremonies, Oriental and Egyptian gorgeousness, and indefinable mysteries of life, death, and torment, were daily—or rather nightly—commonplaces to me before I was six years old. Today it is the same, save for a slightly increased objectivity.’

Anyone familiar with Lovecraft’s letters (many hundreds of which have been published by August Derleth of Sauk City, Wisconsin) will appreciate these statements, for they show him to have been an extraordinarily ascetic and self-effacing kind of writer, the absolute antithesis of Crowley, whose personal extravagances are well known.

It is evident that both Lovecraft and Crowley were registering communications from an unknown source. The equally sensitive, and, in his way, equally austere. Austin Osman Spare, also sensed these forces looming behind Lovecraft’s work. The present writer once gave Spare a volume of Lovecraft’s stories to read. It inspired him to illustrate the horror of these vast cosmic presences. He felt them pressing on his consciousness, almost paralyzing movement.

It is inevitable that one such as Lovecraft, with deep elemental contacts, should at some time or other have worshipped pagan gods, and so he did: “I have in literal truth built altars to Pan, Apollo. Diana, and Athena, and have watched for dryads and satyrs in the woods and fields at dusk. Once I firmly thought I beheld some of these sylvan creatures dancing under autumnal oaks; a kind of “religious experience” as true in its way as the subjective ecstasies of any Christian. I have seen the hoofed Pan and the sisters of the Hesperian Phaethusa”.

In Lovecraft’s case, these pagan gods were veils or masks concealing entities such as those invoked by the author of Necronomicon. Austin Spare alluded to them as “intrusive familiars”.

Invasion by Dark Forces

Lovecraft. Crowley, and Spare, were consistent witnesses of worlds beyond the range of normal human perception. Lovecraft describes their denizens as existing “not in the spaces known to us, but between them. They walk calm and primal, of no dimensions, and to us unseen”.

It was Lovecraft who “ghosted” for Harry Houdini, the illusionist, when he published the story Imprisoned with the Pharaohs, which first appeared in Weird Tales, May 1924; and even this story, although a commissioned work, reveals Lovecraft’s profound insight into the dark mysteries of elder magic.

Lovecraft was greatly influenced by Lord Dunsany and Algernon Blackwood, but his real inspirer and guru was Arthur Machen, the Welsh writer of macabre tales who fulfilled for Lovecraft the role that Poe filled for Baudelaire. Machen fired Lovecraft’s imagination with his stories about the curious underworld creatures that feature as the dwarfs of fairy lore. “Prior to the Druids.” wrote Lovecraft. “Western Europe was undoubtedly inhabited by a squat Mongoloid race”. This was a favourite theme with Machen, and it crops up in many of his wonderful tales such as The Shining Pyramid, The White People, and Change. Lovecraft imbued this concept with the even more sinister idea that these stunted creatures—initiates of an evil faith—derived their knowledge from beings not of this earth, entities outcast ages earlier, now lurking on the periphery of human consciousness in the outermost chaos, waiting—ever waiting—to gain access once more to the life-wave of human evolution.

Lovecraft writes of cosmic intercourse between monsters bred of magical spells in earliest times: they spawned races of witches and warlocks which later peopled the earth and called down upon themselves the anathemas and interdicts that have characterized the history of witchcraft ever since.

Grotesque mutations engendered in voids beyond the known universe possess, by a kind of magic superior to any known upon earth, the power to project themselves into the sleeping minds of men. They come as “a colour out of space” or as “a shadow out of time”, obsessing the mind with strange imaginings that drive men out of their senses, thus making them vacant vehicles fit for invasion by dark forces.

Lovecraft’s Cult of Cthulhu and of the abhorred Yog-Sothoth, who is both the Key and the Guardian of the Gate through which the Great Old Ones pour their baleful power, echoes many of the images to be found in the communications which Aleister Crowley received from unknown dimensions.

Through dreams such as Lovecraft’s, contact is established with ancient sources of wisdom forbidden to man. Perhaps his premature death at the age of 47 was precipitated by the fear of what would happen to humanity if certain Gates were opened. He knew the secret Calls and knew also that one day they would be used again. •

Man, Myth and Magic no. 84, 1971.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• MMM in IT

• The Occult Explosion

• Kenneth Grant, 1924–2011

• Wilfried Sätty: Artist of the occult

• Owen Wood’s Zodiac

• Austin Osman Spare

We have the bound set at home of MM&M and this bit does not ring familiar so much thanks for posting. More Kenneth Grant available is always a good thing in general as his books are hard to come by.

I wonder if Lovecraft, or any of his circle such as Smith for that matter, could lucid dream? I’ve been able to do so as long as I can remember. Though periods of the more visceral forms of it come but rarely, some of the phenomena associated with it can be quite intense. Beyond the Wall of Sleep, Hypnos, and several others could have been directly inspired by some of them, though I guess I’ll never know.

The following is surprisingly balanced in interpretation, given its source.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucid_dream

Joe: Grant also wrote the MMM entry for Atavisms which features several of Spare’s pictures, and also relates a typically dark anecdote. That piece was my first sighting of any of Spare’s art.

Wiley: I’ve never read Lovecraft’s letters so I don’t know if he mentions lucid dreaming but some of his nightmares (which he transcribed) did seem particularly vivid. Either he had a habit of waking in the middle of dream cycles or he had a very good recall. Some of the less obvious stories such as The Music of Erich Zann read like they were fleshed out from nightmares.

None of Lovecraft’s letters (or those of Smith or Robert E. Howard) mention lucid dreaming as such, though they all give descriptions of various fantastic dreams, several of which found their way into fiction one way or another.

I think it’s important to emphasize Grant’s continuing influence on the Lovecraftian occult; certainly his interpretation of Lovecraft as an unconscious adept transmitting real occult truth through the medium of fiction has influenced at least two recent (if specious) biographies – Paul Roland’s “The Curious Case of H. P. Lovecraft” (2014) and Donald Tyson’s “The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft” (2010).

Another interesting similarity between Lovecraft’s work and that of actual practicing esotericists comes from the writing of Peter Carroll. Here and there, Carroll alludes to what he refers to as a ‘psychic censor’, a kind of abstract mechanism that has evolved in modern humans to forcefully blot out experiences and memory of mental phenomena commonly categorized as paranormal or pseudo-sciences, in order to render people more compatible to the mundane hive-mind schematic of modern society.

Apparently, this mechanism often becomes active during dreams, and, should you choose to believe Carroll, is the reason most people remember almost none of their dreams. The effects of the psychic censor are said to be violent at times, aggressively interrupting dreams or visions inspired by prescient or telepathic impulses in a most visceral manner.

Could the soul-searing fear that interrupts his acquisition of some critical discovery that recurred in his writing be an effect of the so-called psychic censor? All-but impossible to prove, but just as unlikely to disprove just the same. Matters of abstract nature elude fixed quantification.

Skeptics would be written off as sceptics much less often would they but acknowledge that nearly all of the artifices and knowledge they rely upon were not brought into being in sterile academic environments. Rather they were borne out during intense contemplation, of the very variety materialists are incapable of quantifying no less, during which men like Tesla, Ramanujan, and Da Vinci occasionally described somewhat surreal experiences.

That’s an interesting thesis, and one you could make use of in a fictional context. I’d be a little wary of adding another theory to the often wild claims loaded onto evolutionary psychology. Which hive-mind: the western or eastern variety? And which period of modernity? Pre-industrial, industrial or post-industrial. Etc.

On the other hand, psychedelic drugs demonstrate that our minds really do operate perceptual filters (or censors) which reduce the intensity of day-to-day experience. Evolutionary psychology has explained this by proposing that without the filters it wouldn’t have been possible to concentrate on matters of basic survival. That much makes sense; maybe Carroll’s filters could be looked at along those lines?

Yes, I’d added ‘should you choose to believe Carroll’ because I certainly don’t agree with him on everything. Also why I chose to describe this idea as all-but-impossible to either verify or discredit. At the risk of sounding redundant, I too agree that ideas like this are better off put into artistic and aesthetic context than anything else. Anyway, I am not a scientist, yet certain matters falling within its arena interest me just the same.

Really I prefer visual mediums and music for the most part anymore because, for me, finding authors whose views they preach don’t become redundant to the point of irritation to my mind, almost never happens. I am probably not much better, if at all, but this one of the reasons I don’t write nearly as much as I use to. I still do enjoy comics, certain comics, quite a lot. As Mr. Moore states time and again though, these should be seen as their own medium.

I really hope your questioning of my throwing about words like ‘hive-mind’ or ‘modernity’ was just part of the point you were making, rather than of your being literally curious as to what I specifically meant. As for the latter, there is no manner in which to expound my thoughts on such things in a timely and efficient manner.

As for your mention of psychedelics, I am pretty sure Carroll made use of them during his experiments and excursions, at least early on.

There’s a lot of things in psychology that can’t be proved in the usual scientific sense–Freud and Jung’s models of the mind, for example–but that doesn’t stop them being useful as metaphors or maps.

I was being a bit nit-picking with my earlier comment, raising the objection that it’s difficult to conceive of evolution developing something that applies to a very short-lived set of human circumstances such as recent social arrangements. Carroll no doubt has a more detailed explanation of his ideas.