Unheimlich Manoeuvres by Feuilleton on Mixcloud

Presenting the ninth Halloween playlist, and another mix of my own. The one last year was pretty abrasive so this year I’ve put together something that’s more concerned with atmospherics and dynamics than jangling the nerves. There’s some continuity in the presence of Roly Porter who brought things to a thundering conclusion last year and does the same here with the final piece from his tremendous Life Cycle Of A Massive Star.

Some of the other music is a bit more obscure than usual, even by my standards. A few people will know that Lull is the name used by Napalm Death’s Mick Harris when fashioning doomy ambience; The House In The Woods is Martin Jenkins aka The Head Technician from Pye Corner Audio; Isnaj Dui is British musician Katie English; Mandible Chatter is (or was) a US duo, Grant Miller & Neville Harson who recorded several uncategorisable albums in the 1990s. Blessings From The Kingdom Of Silence is from their fifth release Food For The Moon (1997), an album I picked up secondhand which I’m surprised to find was a limited edition of 100 copies. As a consequence you may not hear this piece elsewhere.

As before, the tracklist is on the Mixcloud page but I’m repeating it here with dates added for each recording.

Jerzy Maksymiuk — Title music from ‘The Hourglass Sanatorium’ (1973)

Cyclobe — Wounded Galaxies Tap At The Window (2010)

Larry Sider & Lech Jankowski — Sounds & music from ‘Street of Crocodiles’ (1986)

Lull — Thoughts (1994)

Lustmord — The Cell (2002)

Robin Guthrie & Harold Budd — Halloween from ‘Mysterious Skin’ (2005)

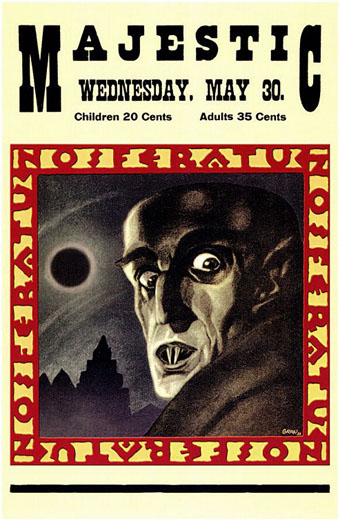

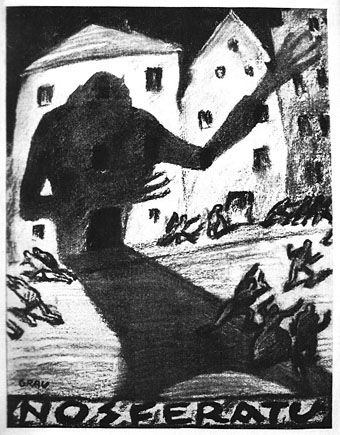

Popol Vuh — On The Way from ‘Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night’ (1979)

The House In The Woods — Dark Lanterns (2013)

Sussan Deyhim — Possessed (2008)

Isnaj Dui — North (2013)

Mandible Chatter — Blessings From The Kingdom Of Silence (1997)

Paul Schütze — The Rapture Of The Drowning (1993)

Roly Porter — Giant (2013)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A mix for Halloween: Ectoplasm Forming

• A playlist for Halloween: Hauntology

• A playlist for Halloween: Orchestral and electro-acoustic

• A playlist for Halloween: Drones and atmospheres

• A playlist for Halloween: Voodoo!

• Dead on the Dancefloor

• Another playlist for Halloween

• A playlist for Halloween