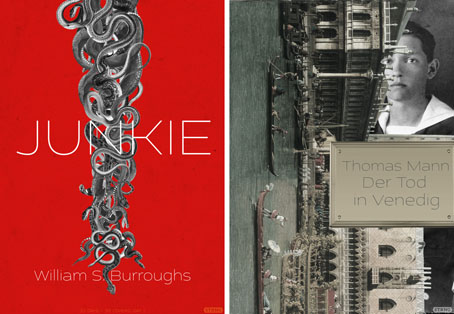

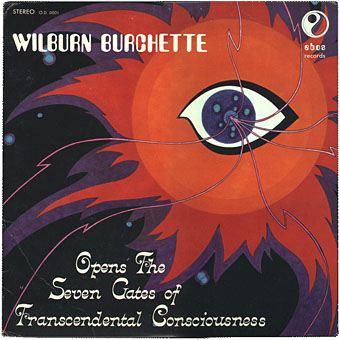

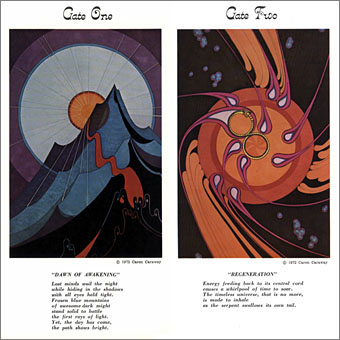

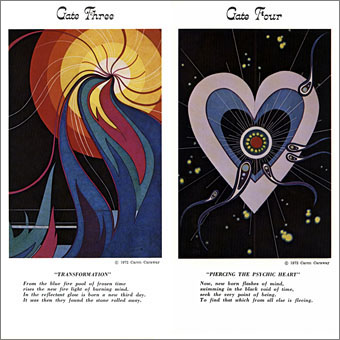

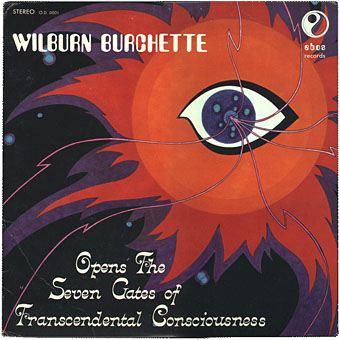

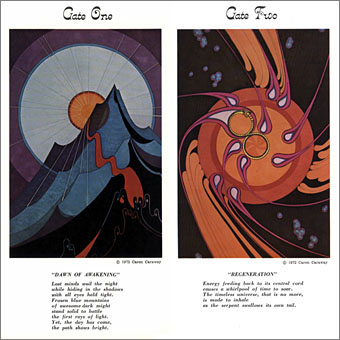

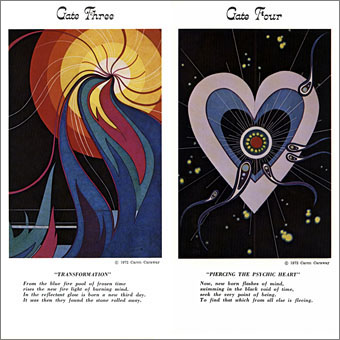

Wilburn Burchette Opens The Seven Gates Of Transcendental Consciousness (1972). Art by Caren Caraway.

For the next two weeks I’ll be playing out the end of the year with a 2-CD compilation from Light In The Attic, I Am The Center (Private Issue New Age Music In America, 1950–1990), 20 tracks of ambient/meditation music, most of which has never been widely distributed before. The “New Age” label is a thing I’ve loathed for years so buying this has meant trashing a decades-long embargo; it helps to examine your prejudices now and then.

New Age in the 1970s referred, among other things, to the oft-promised, seldom-evident “Age of Aquarius”, a term vague enough to be used on albums by Steve Hillage, Manuel Göttsching and others without referring to anything specific. In the 1980s it was taken up by publishers as a marketing label, a catch-all for anything “spiritual” or mildly occult. (I can’t imagine the Goetic Demons ever being called New Age, even if you sprayed them pink.) Out went all the witchy strangeness of the occult boom of the 1970s—spiky typefaces, magical primers sold like Dennis Wheatley novels—in came a profusion of pastel shades, airbrushed pyramids and sparkly, crystal things. Having a fondness for the witchy strangeness I wasn’t impressed. I was even less impressed when New Age became a prevalent label for a style of instrumental music which was too obtrusive to be ambient (in the Brian Eno sense of the word), and also too bland and unassertive to be either jazz or electronica. The popularity of labels such as Windham Hill meant that the large record chains started using New Age as another catch-all label, this time for anything that wouldn’t fit the rock, jazz or folk categories. Along with Windham Hill releases you’d find Eno’s ambient recordings, Harold Budd, Jon Hassell, various German things like Cluster, and anything else that resisted easy labelling. The way the music business tries to hammer everything into a small number of boxes has always been annoying but this seemed like a major insult, hence my loathing of the term.

I Am The Center is a curious album in that it embraces both the recent New Age music label while also harking back to the spiritual yearnings of the 1970s. The general effect is of an impossible collision between the Harold Budd of Pavilion of Dreams, Steve Hillage’s Rainbow Dome Musick, and the lighter moments of Alice Coltrane. Many of the tracks are so good I’ve been searching through Discogs.com to discover more about the artists which is how I came across this album art from Wilburn Burchette. Witch’s Will is Burchette’s track on I Am The Center, from his Guitar Grimoire (1973) album. Looking through his discography, with its attention-grabbing titles and cover art, it’s surprising that his albums haven’t yet been reissued. This will no doubt change soon, especially when his music is like an American equivalent of Achim Reichel’s spacey guitar improvisations. The sleeve and booklet art for Wilburn Burchette Opens The Seven Gates Of Transcendental Consciousness is by Caren Caraway, and the album features notes by the indefatigable UFO/paranormal researcher Brad Steiger. They really don’t make them like this any more.

Joe Muggs enthused about I Am The Center last month for FACT. As I said about the Outer Church album earlier this year, compilations provide an invaluable service in concentrating the attention on overlooked or under-examined areas of music. I’m looking forward to seeing what emerges in the wake of this one.

Continue reading “Opening the Seven Gates of Transcendental Consciousness”