Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1520–1540) by Lucas Cranach the Elder.

It doesn’t take much effort to refute the jeremiads of those who complain that popular culture is exclusively violent, all that’s usually required is to direct attention to Titus Andronicus or The Revenger’s Tragedy. Compared to the stage, the art world seems at first to be more circumspect, especially in the 19th century when the battles scenes of history painters sprawled across acres of canvas, all of them devoid of the physical trauma of warfare.

The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1455–60) by Giovanni di Paolo.

There are exceptions, however, and the nearer you move to Shakespeare’s time the more examples you’ll find. Paintings produced in an age when violent street executions were still a common sight would have seemed less surprising to their intended audience than they do to our eyes. Several of the paintings here provide a useful contrast with the many sanitised depictions of John the Baptist’s severed head in the Salomé archive.

Medusa (c. 1590) by Caravaggio.

Of all the paintings of Medusa’s head the one by Caravaggio is the sole example with a gout of spurting blood. It’s also unusual for being painted on a convex panel intended to resemble the reflecting shield of the Gorgon’s killer, Perseus. Given the violent life of the artist the gore isn’t so surprising although the jet of red in his painting of Judith beheading Holofernes still seems shocking if you’ve never seen it before.

Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598–99) by Caravaggio.

The Biblical story of Judith and Holofernes may be the poor cousin to the more popular story of Salomé but depictions of the crucial event make an impression by being consistently gruesome. I suspect the reason is less to do with the story itself than with the success of Caravaggio’s paintings among cultured Europeans. The copying or imitation of celebrated works became a thriving industry in the days of the Grand Tour with the result that 17th- and 18th-century art is overburdened with variations on earlier paintings.

The Head of Medusa (c. 1617–18) by Rubens.

A great Medusa by Rubens with the blood of the monster giving birth to a host of wriggling serpents.

Judith and Holofernes (1620–1621) by Artemisia Gentileschi.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting is notable for being a painting of a powerful woman that happens to be painted by a female artist. The figures are also more successful than in the Caravaggio where Judith’s lack of exertion makes her look more like a woman adopting a pose than someone butchering a man. Valentin de Boulogne (below) produced one of many similar variations on Caravaggio’s original.

Judith and Holofernes (c. 1626) by Valentin de Boulogne.

Triumph of the Guillotine in Hell (1795) by Nicolas-Antoine Taunay.

From the Bible to a Biblical inferno and a scene which satirises the Terror of the French Revolution. Needs to be seen at a larger size to appreciate its myriad details.

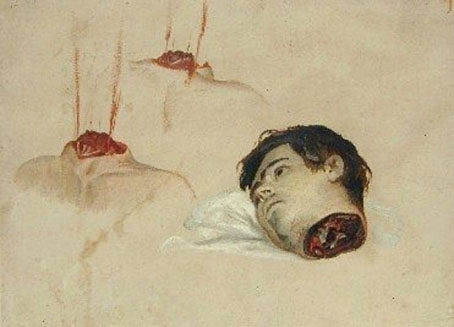

Study of the Heads of Torture Victims (1818) by Théodore Géricault.

Géricault famously studied the condition of body parts in order to accurately depict the corpses in his masterwork The Raft of the Medusa (there’s that name again).

Head of a Guillotined Man (1818–19) by Théodore Géricault.

Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head: First minute. On the scaffold. Center: Second minute. Under the scaffold. Right pane: Third minute. Into eternity (1853) by Antoine Wiertz.

Antoine Wiertz (1806–1865) was a Belgian artist whose inflated ego and morbid preoccupations give Salvador Dalí a run for his money, as well as making him a precursor of the Surrealists. Wiertz convinced the Belgian government to create a museum for his vast canvases among which there’s his unfinished Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head, a triptych which seeks to portray the execution and passing into death of a condemned man. This fascinating essay examines the preparations for the painting which included Wiertz and friends attending a real execution where the painter was hypnotised in order to fully identify with the plight of the executee. He seems to have had an obsession with this subject although it’s not so far removed from the content of his other paintings which feature cannibalism, suicide and a burned child among their delights.

Guillotined Head (1855) by Antoine Wiertz.

Study of a Severed Head by Antoine Wiertz.

Andromache (1883) by Georges Rochegrosse.

Rochegrosse might have been an academic painter but that wasn’t going to stop him lashing his canvas with crimson in this scene from the Little Iliad. Here he shows the moment when Astyanax has been taken from his mother prior to being thrown to his death from the walls of Troy.

The Martyrdom of St Denis (1885) by Léon Bonnat.

And after that nightmarish scene it seems best to end with a moment where a severed head is in the process of being restored (or at least retrieved) in this surprisingly bloody painting which can be seen on the wall of the Panthéon in Paris.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Salomé archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Masks of Medusa

I saw the traveling Artemisia Gentileschi show in St. Louis… And there’s an earlier Judith and Holofernes by her, connected to her rape by Tassi (and her subsequent thumbscrew torture–let’s get the truth!) according to some critics.

Interesting post–feel as if I’ve never seen Wiertz before…

Thanks, I didn’t know there were others by her but then these posts are often a skate over a subject that requires a lot more study. Her version certainly seems more heartfelt than many of the others where Judith might be carving bread rather than killing a man.

Oh, and Wiertz is a good nominee for most eccentric artist of the 19th century. Vast canvases of singular grotesquerie. Belgium has a reputation among sneering Brits for being a kind of boring version of France but it’s produced many unique artists with notable Symbolists and Surrealists (Magritte and Delvaux), as well as the later generations of comic artists.

Hang on…

Here’s the earlier one. And it says she uses Tassi’s face for Holofernes, so that settles that dim memory! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_Slaying_Holofernes_(Artemisia_Gentileschi)

Ah, I did see that one last week when I first had the idea for this post. Thanks!

My inner pedant vomits forth: surely this scene is not in Homer’s Iliad, which doesn’t cover the sack of Troy.

I misread a reference, should be the Little Iliad for that particular scene although it’s described in a number of other texts any of which might be the origin for the painting:

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/40140/Astyanax

Absolutely. I’ve no quarrel with the episode’s being an accepted part of the story of the fall of Troy, but to have gone on at greater length would have been grotesquely unpleasant, rather than merely annoying, and might have looked like I was pretending to an erudition I lack.

One of the virtues of the Iliad is where it stops:

“The figures are also more successful than in the Caravaggio where Judith’s lack of exertion makes her look more like a woman adopting a pose than someone butchering a man.”

The artistic “success” of the figure is relative, I prefer Caravaggio, but you miss the crucial element of time in each depiction.

Gentileschi paints a Judith mid struggle apparently having woken her victim prior to a fatal cut with maid’s help required as she saws away.

Caravaggio shows an instant, the throat is cut the gout of blood not yet staining the sheets is his first waking heart beat from a ‘dead sleep’ and Judith is exerting no effort because there is no struggle, the hand in his hair starting as a caress before that of steel. She is not posing but showing surprise in the moment. Compare her expression with the more wizened maid’s who seems to be anticipating the mess.

This post was so thoroughly interesting and exciting it jolted me from an uninspired and undercaffeinated mood into a much better one!