weird, a.

1. Having the power to control the fate or destiny of human beings, etc.; later, claiming the supernatural power of dealing with fate or destiny. Originally in the Weird Sisters = †(a) the Fates; (b) the witches in Macbeth.

2. a. Partaking of or suggestive of the supernatural; of a mysterious or unearthly character; unaccountably or uncomfortably strange; uncanny.

b. of sounds or voices.

3. Of strange or unusual appearance, odd-looking.

4. a. Out of the ordinary course, strange, unusual; hence, odd, fantastic. (Freq. in recent use.)

b. Colloq. phr. weird and wonderful, marvellous in a strange or eccentric way; both remarkable and peculiar or unfathomable; exotic, outlandish. Freq. ironical or derog.

5. Comb., as weird-looking adj.

Oxford English Dictionary

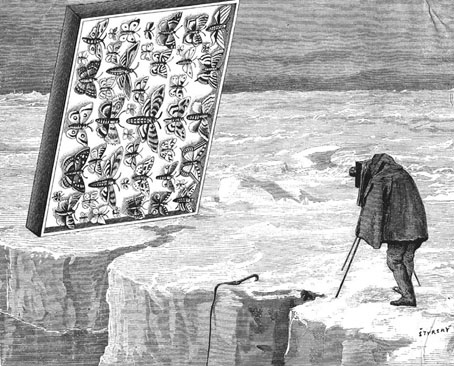

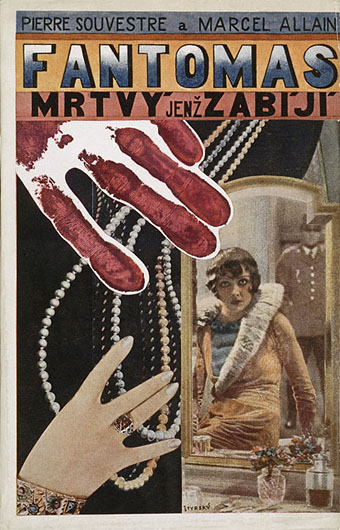

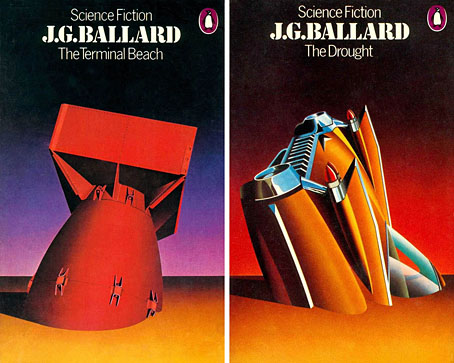

Weird: I’ve relished the word since I was at school for the way it managed to embody or describe so many of the things I was deeply attracted to, especially in the world of fiction. Weird Tales magazine when it was at its height in the 1930s was able to publish stories of fantasy, horror and science fiction, or hybrid stories of fantasy/horror or horror/sf, none of which needed to be alloted specific definitions when “weird” was there to cover everything. China Miéville noted the usefulness of the “weird” designation ten years or so ago, and I’ve been hoping ever since that other people might pick up the broader, more inclusive term instead of dividing the major genres into ever smaller sub-genres. “Weird” could accommodate generic work but also encompass those stories that were simply strange without possessing the usual genre trappings.

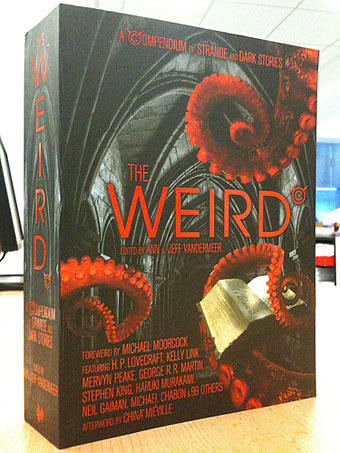

So far the term hasn’t found the widespread favour I’d been hoping for but that may change thanks to the Weird Fiction Review, a site launched this week by my friends and occasional collaborators Ann and Jeff VanderMeer whose enormous brick of an anthology, The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories, is published by Corvus this month. Weird Fiction Review states that:

its primary mission over time will be to serve as an ongoing exploration into all facets of the weird, in all of its many forms—a kind of “non-denominational” approach that appreciates Lovecraft but also writers like Franz Kafka, Angela Carter, and Shirley Jackson—along with the next generation of weird writers and international weird.

Already on the site is an interview with Neil Gaiman who says:

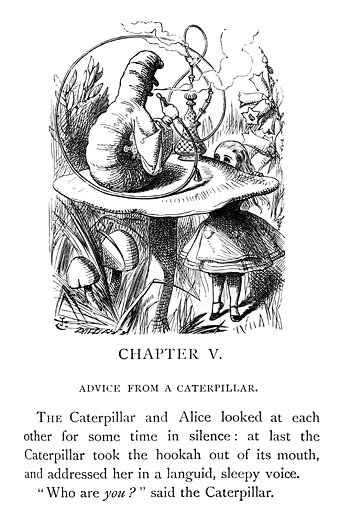

I think of Horror as a section of a bookshop, gothic as a type of book that ended, truly, with Northhanger Abbey, and The Weird as an attempt to unify whatever it was that Robert Aickman did, that Edward Gorey did—using the tools of horror to delight and transform.

I’m re-reading some of Aickman’s stories at the moment. He called them “strange” but I’d call them 100% weird. There’s one in Ann & Jeff’s anthology whose contents are an ideal introduction to this zone of literature.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Vengeance of Nitocris

• Die Andere Seite by Alfred Kubin

• The King in Yellow

• Hugo Steiner-Prag’s Golem