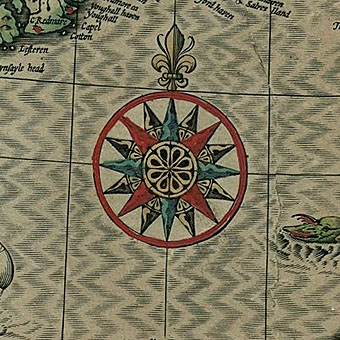

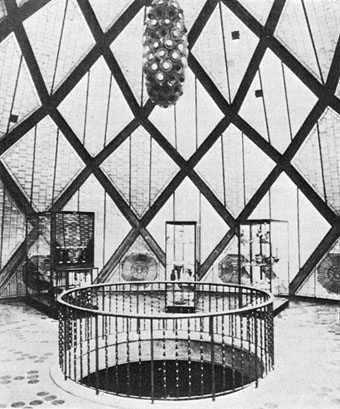

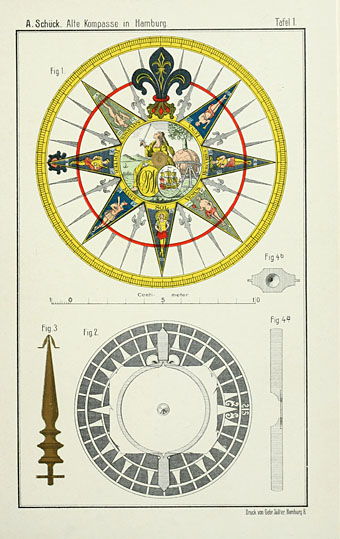

Compass rose by John Speed (1610).

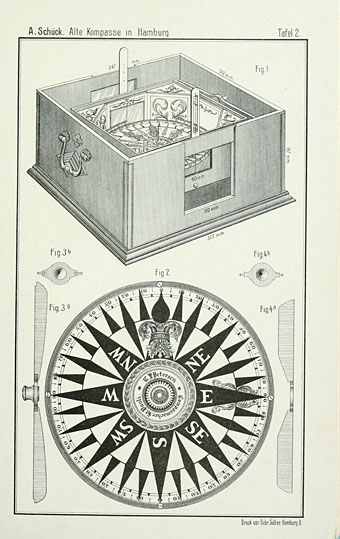

Be still, my beating heart… Every so often this graphic designer has been known to complain that there isn’t a decent resource for those cartographic details known as compass roses. Well today I hit the motherlode with the discovery of Alte Schiffskompasse und Kompassteile im Besitz Hamburger Staatsanstalten (1910) by Albert Schück at the Internet Archive. Schück’s book is a small study of the evolution of the compass card from crude diagram to the elaborate creations seen here, bedizened with astrological figures or divided into degrees. The plates are exactly the kind of thing I’ve been after for years, not that I need them for any particular purpose but—given that I fetishise these things—it’s good to have them to hand.

Part of the obsession can be traced to the compass rose on John Speed’s map of Great Britain and Ireland (above). My teenage bedroom walls included among their pictures a facsimile of Speed’s map printed on some peculiar plasticised paper which (as I recall) was supposed to make it look an antique print. When drawing maps of my own I’d usually copy Speed’s compass rose, and familiarity with the device meant that I started searching them out whenever I saw another old map. Also on the bedroom wall was Pauline Baynes’ map of Middle Earth which includes a compass rose of its own.

BibliOdyssey posted a nice selection of Speed maps recently, all of them hand-coloured (my reproduction was black-and-white). Speed’s compass rose for the Isle of Man makes the island appear to be the centre of the world. Also at the Internet Archive is a similar study to the Schück, The Rose of the Winds: The origin and development of the Compass-Card (1913) by Silvanus P Thompson. This is more useful if your interest is in the actual history of the cards since the diagrams are a lot less extravagant. Among other things Thompson refers to Schück’s volume in a note about the origin of the fleur-de-lys figure as a compass fixture. “Rose of the Winds” refers to the very earliest compass devices in which directions were marked not with North, South, East and West but with whatever the local names were for the winds at sea.